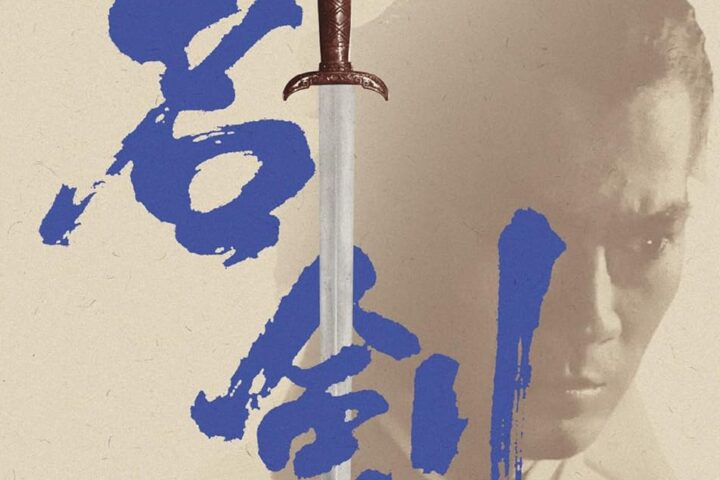

Due to the vagaries of rights acquisition, it has taken Arrow Video three volumes of its indispensable Shawscope series to offer the movie that started it all in terms of Shaw Brothers Studio’s ascent to the top of the Hong Kong box office: Chang Cheh’s groundbreaking 1967 wuxia The One-Armed Swordsman. As such, it can be easy to take for granted Chang’s ultraviolence and grim thematic undertones given how many later, more refined efforts from Chang and other filmmakers have already been released.

Nonetheless, The One-Armed Swordsman’s economy of pacing and visceral transmission of its hero’s rage give the film a power undiminished by the host of copycats that flooded the Hong Kong market over the next decade. Jimmy Wang Yu’s maimed warrior, Fang Kang, cuts an instantly iconic profile: hair bound in a fin-like top knot and beard honing his jaw to a point, Fang looks as sharp as his blade, and the fury in every gesture does as much to capture Chang’s revisionist take on the genre’s notion of honor and nobility as the plot mechanics.

The set also comes with Chang’s sequels to the hit, 1969’s Return of the One-Armed Swordsman and 1971’s The New One-Armed Swordsman, neither of which reaches the heights of the first. Nonetheless, they both show the director’s increasing command of visual tone, with gloomy color palettes that cast a deathly atmosphere over otherwise straightforward retreads.

But the standout filmmaker among those whose films are gathered here is Chor Yuen. If Chang’s work gradually refined his thematic and aesthetic tics into a honed edge, Yuen’s output for Shaw Brothers was far more eclectic, often varying wildly in approach and tone.

The Magic Blade, from 1976, is set mostly at night and marked by expressionistic lighting choices that initially scan as moody, but above all else the film feels like a journey through a funhouse. The hero (Ti Lung) navigates a constant series of ambushes and booby traps that force him to deal with increasingly elaborate weapons and scenarios, most notably a battle that doubles as a game of living chess. In the following year’s The Sentimental Swordsman, Yuen takes the material far more somberly, communicating characters’ emotional states and romantic yearnings almost entirely through the actors’ and camera’s movements.

Two other Yuen films—the dark revenge tale The Jade Tiger and the convoluted whodunit Clans of Intrigue, both from 1977—are relatively generic in terms of plot but demonstrate Yuen’s idiosyncratic use of color and framing. The real gem of his work represented here is 1972’s Intimate Confessions of a Chinese Courtesan. In it, a brothel madam (Betty Pei Ti) who forces young women into sex work and takes a particular interest in one girl, Ainu (Lily Ho), whom she not only instructs but takes as a lover. The slow-burn drama unfurls initially as a bleak melodrama before Ainu begins to act out an elaborate plan of revenge on her tormentors. Yuen’s florid palettes and swooning camerawork are on full display, but he uses them to lure in the viewer before curdling the images into something grotesque and nihilistic as he foregrounds the victims who rarely get to have a voice in either actual history or wuxia’s presentation of it.

The rest of the set is devoted to works by some of the studio’s workman directors, and though they may lack the distinctive stamp as Chang and Yuen’s films, they aren’t without their own flair. One of Ho Meng-hua’s most entertaining efforts is 1971’s Lady Hermit, an elementally simple story of a martial arts master (Cheng Pei-pei) who ends up in a love triangle with two pupils (Lo Lieh and Shih Szu) amid training to take down a warlord and his army. From the striking color and lighting contrasts from cinematographer Danny Lee Yau-tong to intricate fight choreography and some surprisingly intense gore, this is a propulsive thrill-ride.

At times, Lady Hermit feels almost like a video game in its progression through enemies. Sun Chang’s The Avenging Eagle, from 1978, leans more heavily on master shots during action sequences than most of the films in the set, stressing the balletic quality of the choreography and the underlying melodrama that’s a core aspect of even the most violent wuxia.

A more somber drama, Cheng Kang and Charles Tung Shao-yung’s The 14 Amazons doesn’t fully work, as its intriguing premise—a gender-flipped take on men-on-a-mission revenge tale—is undermined by pacing issues. Even so, the 1972 film is a fascinating hybrid of Chinese opera and American western, at times offering up vistas that suggest the influence of John Ford.

More successful in its downbeat tone is Kuei Chih-hung’s 1980 antihero classic Killer Constable, a film so bleak in its depiction of “justice” as legal barbarism and society as a perpetual exploitation of an underclass by a ruthless elite that it makes Chang Cheh’s revisionist work look sunny by comparison. Its heavy use of mood lighting, expressionist shadows, and bursts of bloody red only compound its nihilistic atmosphere. Befitting the director’s usual work in the horror genre, Killer Constable works just as well as a monster movie as a martial arts one, albeit one where the monsters are the villains and nominal heroes both.

The more Shaw Brothers titles make it to video, the clearer it becomes that even the studio’s most distinctive works adhere to a number of narrative and stylistic formulae. As such, one of the great delights of these sets are selections from the studio’s post-peak era in the early 1980s, when loss of market share to rival companies led to a willingness to shake up stale tropes.

Things don’t get much more shaken up than Taylor Wong’s Buddha’s Palm, which functions less as a story-driven work than a repository for as many stylistic nods as it can manage, no matter how poorly they fit together. The 1982 film draws equally from the loopier end of Hong Kong cinema, and with the kind of wacky special effects that John Carpenter would send up with Big Trouble in Little China, as it does from contemporary Western blockbusters. It even incorporates some clear nods to Japanese pop culture, both in its use of manga-esque inserts and a synthesizer score heavily redolent of Yellow Magic Orchestra’s proto-synthpop of the time.

Tony Lou Chun-Ku’s Bastard Swordsman, from 1983, is far more narratively conventional. The story, about an orphan (Norman Chui) raised in a martial arts temple under constant bullying by the students he ultimately saves, is simple, though its form is anything but, as the film moves at a frenzied pace and boasts imaginative, surreal choreography. One duel between rival masters involves a man catching a sword swing with his teeth and an ancient tome being sliced to ribbons until its pages begin to “dance” around the warriors like animated cut-outs.

Elsewhere, our hero hones his sword craft by spearing falling leaves with his blade, before then flinging them to the ground in the perfect shape of Chinese characters. The story of Shaw Brothers Studio is told as much through strange, compelling outliers like Bastard Swordsman and Buddha’s Palm as they are the canonical classics like The 39th Chamber of Shaolin, and if the third volume of Shawscope has fewer “name” titles than its predecessor, the sheer range of the material gathered makes it arguably the most interesting and surprising of the sets to date.

Image/Sound

All of the films in Arrow Video’s set are sourced from 2K restorations save for the 4K-restored The One-Armed Swordsman, and predictably all of them look terrific. Color balance, black levels, and contrast are stable across each film, and detail is sharp enough that you can spot all the tiny, endearing flaws of the cheap weapons props, along with the more delightful textures of costumes and set design. The soundtracks are similarly blemish-free, with the dubbed dialogue always crisp at the front of the mix amid the clang of steel on steel and the mixture of swooning strings and bubbling synthesizers used across the various scores.

Extras

Each film comes with at least one, and sometimes as many as three, commentary tracks from various critics and enthusiasts like Hong Kong film expert Frank Djeng. There are also plenty of archival interviews with various actors and filmmakers whose work appears in the collection, as well as a 40-minute interview with critic Tony Rayns on the career of director Chor Yuen. We even get a VHS rip of an alternate cut of Killer Constable for the Korean market that runs longer than the Hong Kong version. A bonus CD contains music from various films.

Overall

Arrow offers up yet another indispensable collection of Hong Kong cinema classics, lovingly restored and supplemented with a trove of extras, from the vaults of Shaw Brothers Studio.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.