Although the extent to which the iconically dark-shaded and silver-streaked Guido Anselmi (Marcello Mastroianni) can truly be accepted as a Federico Fellini surrogate is a source of endlessly inconsequential debate, we tend to take the lightly fictive director at his word when he dismally claims that he had planned to make a truly honest and direct film this time around. 8½ represents the most unceremonious and abrupt transition in the development of Fellini’s cinema from putatively neorealist ideologies to unabashedly oneiric claptraps about the onus of an overly imaginative but waning masculinity—and it is, for all its Freudian bitchery and post-libidinous angst, one of the few personal statements in film utterly unhindered by stretches for social or cosmic relevance.

There are some aphoristic generalizations related to living the creative life, most of them articulated by Guidio’s lean script advisor and logos personification Daumier (Jean Rougeul)—“Destroying is better than creating when we’re not creating those few, truly necessary things”—but unlike the allegorical potency of La Dolce Vita, which rendered Rome with Olympian hedonism and Dante-esque judgment, the symbolism of 8½ maroons us in the faux-comic salt flats of Guido’s muddily incommunicable psyche without an archetypal compass.

More intriguing than the biographical foci at which Guido and Federico intersect is the manner in which the latter seemingly structures the career of the former as a dense, wiry extension of their collective psychic apparatus. There’s no clean way to boil the characters of 8½ down to their psychoanalytical essence. Guido’s superego of a producer (Guido Alberti), strolling meatily through the studios, locations, and galas like a harried Ghost of Christmas Present, asserts the need for financial success against the homunculus Daumier’s thick-veined and equally ego-driven screenplay dissection, but even their grim warnings of filmic failure are meant to remind Guido not of his temperamentally adulating public, but of his pervasive impotence.

And Fellini fails to make a truly meta-movie with 8½ (even though every arcing camera pan and slithering truck shot is deeply and even funnily self-conscious, cinema is best understood here as a cognitive analogy rather than an as a self-reflection), but he unwaveringly embraces cinema as a cavernous expression of the panicked id. It’s as though in the face of creative crisis the director took the self-empowering advice from his own early oeuvre, especially the tearjerking egotism of La Strada and the recalcitrant élan of Nights of Cabiria.

Still, 8½ sings as a self-deprecating comedy, a fact revealed most forcefully in the folly of film production on display and its parallels to sex; Guido’s erect but useless rocket towers are vacant, ominous totems sneering at the director’s coitus non-existus, while the puckish frittering of the non-plot has an “Oh, what fools these cast and crew be” glee. And Fellini makes it clear that his protagonist/stand-in’s humiliation is a self-imposed mechanism, an indelible fantasy meant to excuse away the approaching silence between Guido’s legs after years of animated sexism.

Guido’s arguments with his wife, Luisa (Anouk Aimée), and his mistress, Carla (Sandra Milo), are his only genuine opportunities for intimacy, a pathetic fact underscored by sexless late-night discussions with beatific actress Claudia (Claudia Cardinale) and the degeneration of a toga-laden harem daydream into patricidal pandemonium. Due to Guido’s utter lack of virulence (even after his cathartic self-gunning and resurrection his instinct is to semi-gracefully accept defeat), 8½ belongs to its torrid community of feminine conquests—an interpretation certainly favored by those at the helm of Rob Marshall’s Nine. Fellini’s hyperrealism, for all its poetry, has never been much of a challenge for a fair pair of mammary glands and a fiery temper.

Image/Sound

Criterion’s transfer is sourced from the same 4K restoration used for the label’s Essential Fellini set from 2019. Predictably, the strong contrasts and deep black levels of the 2K disc look even richer and more detailed in native 4K, revealing more textures and subtle gradations between whites and blacks. The restored mono track, which also first appeared in the Essential Fellini set, marks a clear upgrade from the slightly tinny, flat sound on Criterion’s 2010 Blu-ray disc. Separation of dialogue and sound effects is crisper, and there are no artifacts of hissing or pops.

Extras

The extras here are ported over from prior Criterion releases of 8½ stretching all the way back to the label’s 2001 DVD edition, starting with a composite commentary track of actress Tanya Zaicon reading an essay about the film’s symbolism and interviews with critics Gideon Bachmann and Antonio Monda, each of whom discusses various analytical and anecdotal details related to 8½’s making and meaning. A 1969 NBC special on Fellini is an aptly fabulist “documentary” on the filmmaker that covers his life and signature fixations in a manner similar to the director’s own surreal treatment of them. (The disc also comes with a digital facsimile of the letter that Fellini sent to the network outlining his ideas for the special.)

Elsewhere, we get an interview with actress Sandra Milo, who played Guido’s mistress in 8½, and cinematographer Vittorio Storaro and directors Lina Wertmüller, who extol the film’s virtues and its influence on their own work. (Terry Gilliam also celebrates the film in an introduction.) Photo galleries of behind-the-scenes footage are included, along with two substantive documentaries, one a 1993 German TV broadcast about composer Nina Rota and the other a nearly hour-long examination of 8½’s original ending, which Fellini fully filmed but mostly destroyed when he heavily revised the conclusion.

The accompanying booklet contains an essay by critic Stephanie Zacharek in lieu of the one by Alexander Sesonske that came with the 2010 Blu-ray. Zacharek’s essay reflects on Fellini’s up-and-down relationship with the critical orthodoxy over the years and even acknowledges the director’s somewhat diminished popularity of late among cinephiles, even as she argues the enduring influence of both Fellini and his most ambitious masterpiece.

Overall

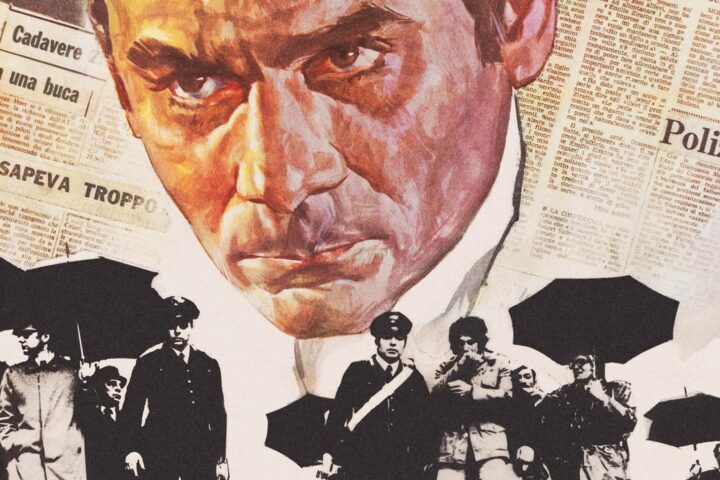

Criterion’s 4K UHD release of Federico Fellini’s 1963 magnum opus presents its gorgeous imagery in all its oneiric splendor.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.