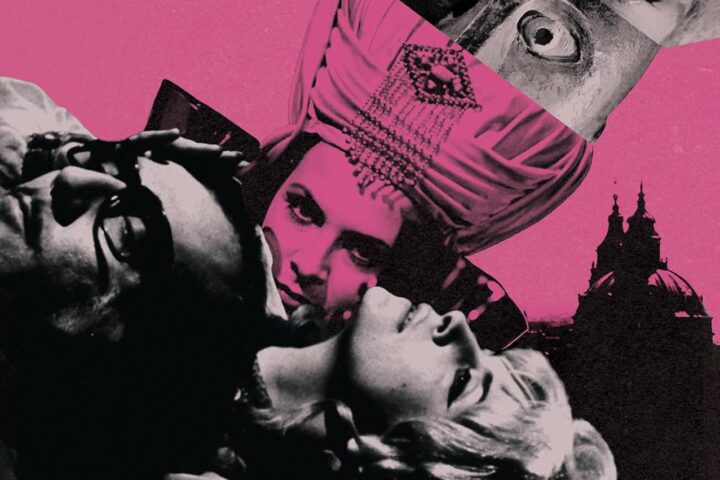

A work of both visceral immediacy and lingering allure, Valerie and Her Week of Wonders is a uniquely influential film, one of intoxicating sensation and unconscious immersion—and one, for that matter, often recognized and referenced more than actually seen. Directed by Jaromil Jireš and released just as Soviet suppression of socialist ideology spread to a similarly strict regulation of the arts, this surrealist fantasy from 1970 represents both the spiritual culmination of the Czech new wave and a brave bid for a newly liberated filmic sensibility.

Based on a novel by the poet Vítězslav Nezval, the film paints its portrait of a young girl’s sexual awakening in highly allegorical strokes, through a mix of gothic imagery, folkloric cues, and mythic conceits. Divorcing narrative from an expositional tradition, Jireš, one of the most pointedly political of all Czech filmmakers, instead frames his young protagonist’s story as a nested, episodic reverie, as a dream within a nightmare with allusions to the grip of communism which threatened to (and eventually did) claim an entire generation of provocative new directors.

Starring Jaroslava Schallerová as Valerie, a naïfish orphan whose coming of age is imagined as a battle for familial, religious, and sexual autonomy, the film proceeds with a free-associative logic, linking passages through images and atmosphere rather than extraneous conversation. Relationship particulars are instead gleaned through Valerie’s impressionable view of those around her: Elsa (Helena Anýžová), her coldly calculating grandmother, who grows fangs and whips herself into submission for her ex-lover Gracián (Jan Klusák), a Catholic priest who in turn sexually torments Valerie in a manner similar to the ferret-faced vampire Polecat (Jirí Prýmek), an eerie figure intent on stealing our heroine’s magical pearl earrings.

Meanwhile, she yearns for the affection of Eaglet (Petr Kopriva), a strapping young lad who may be her brother and who attempts to keep Valerie out of harm’s way while guiding her toward a kind of venereal rebirth. Jireš visualizes this impressionistic journey in alternately soft focus and horrific hues, drifting from moments of tender passion (as when Valerie stumbles upon a group of nubile maidens bathing in a creek) to sequences of psychological and physical abuse (as when she’s forced to watch her grandmother self-flagellate for Gracián’s approval). This balance of the sensual and the sadistic is one of the film’s most disarming qualities, as Jireš conflates notions of pain and pleasure in an equally seductive and severe manner.

The Czech new wave was often defined by a certain investment in social realism, though many of its key works—Daisies, Capricious Summer, and A Report and the Party and Guests among them—utilized artifice as a weapon of equally damning force. Valerie and Her Week of Wonders takes the heightened, sometimes hallucinatory qualities of those films and amplifies them to the point of near abstraction. Released just one year after Jireš’s The Joke, one of the movement’s most strikingly austere works, Valerie and Her Week of Wonders is a film which even now stands apart not only from the director’s own corpus, but from Czech filmmaking at large.

Looking elsewhere, one may note the influence of the New American avant-garde or, more visibly, the work of Armenian director Sergei Parajanov, who himself had released the similarly evocative, intuitively constructed The Color of Pomegranates the year prior. But Jireš isn’t a formalist in the fashion of Parajanov or the then-emerging structuralists. His aesthetic mode is far looser, his approach to montage more fluid, allowing cinematographer Jan Curík’s camera to trace the movements of the actors without sacrificing the natural beauty of the Czech countryside or the gothic magnitude of the sets. The film’s compositions gather an offhand magnetism as they unfold, locating a strange kind of beauty in the grotesqueries of Valerie’s virginal visions.

The accumulated power of the images may, in effect, eclipse any of the film’s individual sequences, but there’s an undeniably hypnotic rhythm to the editing patterns and to Jireš’s coded, ever-shifting color palette, which employs recognizably suggestive symbolism to accentuate character detail and narrative dynamics otherwise not elucidated by the dialogue. Meanwhile, a lilting, vaguely psychedelic score by chamber composer Luboš Fišer weaves amid the imagery, lending the proceedings an even greater air of narcotic, sensual appeal.

The result is a phantasmagoric display of visual ingenuity and aesthetic abstractions, a film which opens up new avenues of consideration and application of the medium’s most fundamental tools by simply reimagining their latent potential. Valerie and Her Week of Wonders may be a willfully enigmatic, even obtuse viewing experience, but every frame continues to vibrant with energy and thrum with life—a life all the more unsettling for its familiarity.

Image/Sound

Criterion debuts Jaromil Jireš’s Valerie and Her Week of Wonders on Blu-ray, and the 1080p transfer is appropriately lush, occasionally verging on luminescent. Colors are sharp and detail is crisp, without sacrificing the soft-focus texture of Jan Curík’s cinematography. Contrast is well balanced, with sunlight and the natural ambiance of the film’s mostly outdoor locations transitioning in authentic fashion. Sound, meanwhile, is kept to a linear, single-channel track, more than adequate to handle the serene aural accoutrements and Luboš Fišer’s gently folk-tinged score. Dialogue is likewise clear and discernible, and the track on the whole features no notable hiss, noise, or audible aberrations.

Extras

The highlight of the supplemental features are three rare, early short films directed by Jireš, including Uncle, Footprints, and The Hall of Lost Footsteps, each of which anticipate Valerie and Her Week of Wonders in unexpected and unique ways. Three video interviews are included, one with Czechoslovak film scholar Peter Hames, and one each with actors Jaroslava Schallerová and Jan Klusák, the latter of whom has less than fond memories of the shooting experience. The music, meanwhile, receives its own special treatment with a fantastic alternate soundtrack performed the Valerie Project (a band led by Greg Weeks of mid-aughts folk troupe Espers, and including various members of Philadelphia’s contemporary psychedelic scene), and a video piece featuring interviews with the band members discussing the inspirations for the project and their relationship with the film. Finally, an informative essay by Jana Prikryl is included in one of Criterion’s typically beautiful booklets.

Overall

Jaromil Jireš’s influential, eternally enigmatic classic arrives on a lush new Blu-ray from Criterion, preserving the film’s soft-focus allure and intoxicating sensuality.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.