The second volume of Severin’s All the Haunts Be Ours brings together a dizzying variety of folk horror titles—some recognized cult favorites, others hitherto obscure—that constitute a fabulist bestiary replete with witches, werewolves, and all manner of vengeful spirits. These 24 films included in the set are spread across 13 discs housed in a hardcover book, accompanied by a booklet with synopses and other information on each film, as well as an attractively illustrated 250-page “Little Severin Book” that collects 10 newly commissioned examples of folk horror fiction from authors like Kim Newman and Ramsey Campbell.

Where the first volume, also curated by author Kier-La Janisse, leaned heavily on Anglophone contributions to the subgenre, with a smattering of titles from Eastern Europe and Italy, the second casts its net wider to include a number of films from East and Southeast Asia. These include Sisworo Gautama Putra’s batshit Sundelbolong, from 1981, about a woman (Suzzanna) who turns into an implacable demon with an unsightly hole in her back after a botched abortion claims her life. Also included on that disc is David Gregory’s excellent new documentary Suzzanna: The Queen of Black Magic, which chronicles the fascinating life and times of the cult film actress whose off-screen persona was often conflated with her wild onscreen antics.

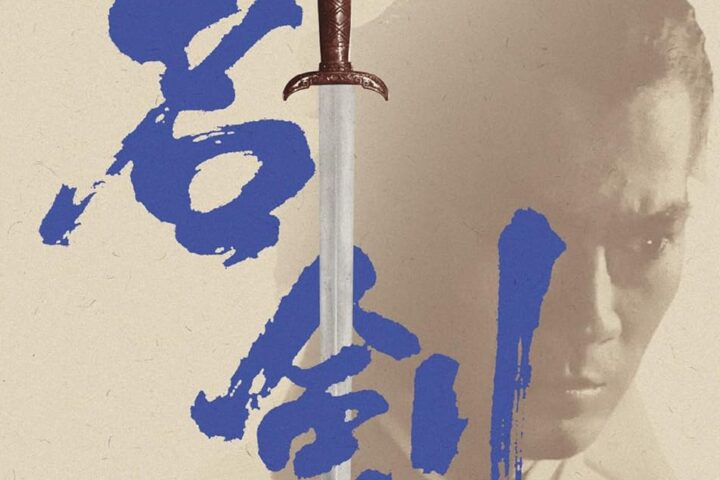

Other films are culturally inflected variations on the theme of otherworldly revenge. Mike De Leon’s The Rites of May, from 1976, sees its debauched patriarch (Mario Montenegro) finally called to atone for his crimes at a séance vividly set against Catholic folk practices of Holy Week. Here the notion of guilt is explicitly linked to the graphic self-flagellation of ritual penitents, so that the Filipino film more fully expresses the suffering commemorated by Good Friday rather than the redemption of Easter Sunday. From 1968, Ishikawa Yoshihiro’s Bakeneko: A Vengeful Spirit uses the titular figure of the ghost cat to punish a wicked feudal lord responsible for the deaths of a young couple. This take on the oft-filmed material is a wild and stylish ride, making spectacular use of the monochrome cinematography and wide Scope frame.

From 1999, Nang Nak reworks a popular Thai folktale about the revenge-seeking ghost of a woman who died in childbirth, but the film chooses to largely deemphasize the spectral stuff, instead playing up the more heart-stirring elements of tragic romance, until it comes dangerously close to a Southeast Asian spin on Jerry Zucker’s saccharine Ghost. Far nuttier, and with a truly gonzo finale that will leave your jaw on the floor, Kim Ki-young’s Io Island, from 1977, uses indigenous practices of shamanism to explore the thorny relations between the sexes on a remote Korean island where the women outnumber the men.

A more ethnographic approach to the institution of shamanism characterizes Erik Blomberg’s 1952 film The White Reindeer. Blomberg chronicles the folkways of Lapp reindeer herders in the far north of Finland with anthropological acuity, while at the same time relating the tale of a woman (played by co-writer Mirjami Kuosmanen) who, after a ritual love spell goes awry, turns into a vampiric version of the titular creature. Through it all, Blomberg effectively contrasts the stark white vistas of the landscape with moody shadow-haunted interiors.

Gwaai Edenshaw and Helen Haig-Brown’s Edge of the Knife, from 2018, goes even further in the ethnographic direction in its attempt to place us squarely in the middle of an unfolding folktale without much in the way of narrative orientation. Filmed in the endangered language of the Haida, a tribe located off the shore of British Columbia, the story recounts the experiences of Adiitsʹii (Tyler York), whose guilt over causing the accidental death of a young boy slowly transforms him into the legendary creature known as a Gaagiixiid. The film subtly signals some major plot revelations along the way that shed intriguing light on the tribe’s personal dynamics.

Varieties of American folklore wend their way through both Carter Lord’s The Enchanted, from 1984, and John Newland’s Who Fears the Devil (a.k.a. The Legend of Hillbilly John), from 1972. The former is an examination of the delicate balance between humans and nature in rural northern Florida, exhibiting some amiably lowkey surrealism and truly impressive artwork along the way. The latter, despite some fleeting nudity in its early minutes, mostly plays like a TV movie gone delightfully off the rails. An Appalachian balladeer (Hedges Capers) with a silver-stringed guitar goes up against a deceptively lovely witch (Susan Strasberg) and a giant ugly bird (rendered in hilariously ropey claymation) as part of his episodic adventures.

A similarly unhinged approach to storytelling marks Persian writer-director Jamil Dehlavi’s Born of Fire, from 1987, and Don Sharp’s trippy Psychomania, from 1973. Set and filmed largely in Turkey, Dehlavi’s film pits a British flutist (Peter Firth) against a master musician who turns out to be a djinn. The imagery tends toward pure surrealism, and Dehlavi wrings maximum effect from Cappadocia’s otherworldly landscapes. Sharp’s film illustrates the hangover of the 1960’s countercultural fascination with occult paraphernalia, tossing in everything from black masses to stone circles. In the film’s most indelible image, undead biker Tom Latham (Nicky Henson) comes roaring out of the grave atop his motorcycle.

But possibly the most histrionic antics in this whole collection can be found in the 1975 Argentinian film Nazareno Cruz and the Wolf. Leonardo Favio’s overheated tale of a seventh son cursed to turn into a werewolf on his 18th birthday makes your baseline frenetic telenovela look like something out of Ozu in comparison. And it also boasts one of the weirdest descents into the underworld this side of Jigoku or a José Mojica Marins Coffin Joe movie.

The ambivalent figure of the witch is the focus of Pedro Olea’s Akellare, from 2000, and John Llewellyn Moxey’s The City of the Dead, from 1960. For Olea, the witches who were persecuted by the Inquisition in 16th-century Navarre were in reality engaged in practices rooted in pre-Christian Basque beliefs, and the film layers in elements of social and political commentary, delighting in exposing the hypocrisy and corruption of the clergy and aristocracy. In Moxey’s film, the coven of New England witches led by Elizabeth Selwyn (Patricia Jessel) are far from victims, since not even burning at the stake can end her baleful reign. The City of the Dead sits on a fascinating cusp between fog-shrouded gothic tales and the more mundane settings of modern-day horror, even recalling another film that came out the same year: Psycho.

Slovak director Juraj Herz is the only filmmaker represented in this collection by more than one title, and that’s a fitting testament to the mesmerizing power of his work. His take on the classic French fairy tale Beauty and the Beast, from 1978, shares a surrealist bent with Jean Cocteau’s 1946 adaptation, but displays a darker, earthier aesthetic: The elaborate sets exude a palpable aura of autumnal decay, and the costume design for the Beast (Vlastimil Harapes) more closely resembles a bedraggled raptor than Jean Marais’s nobly leonine (almost cuddly) embodiment of the accursed figure. Since the Beast’s bird mask precludes much in the way of expressivity, Herz hired a dancer to play the part, thereby letting his comportment do most of the work.

The Ninth Heart, from 1979, audaciously redresses some of Beauty and the Beast’s massive sets but otherwise conveys a rowdier vibe. Herz uses the lively milieu of the puppet theater to frame the tale of a brash student (Ondřej Pavelka) who ill-advisedly gets caught up in a quest for the hand of a princess (Julie Jurištová) who’s fallen under the spell of the nefarious court astrologer, Count Aldobrandini (Juraj Kukura). The result is an ironic sort of fairy tale, where the outcome of the student’s mission fails to bring him any contentment, paving the way for a more modest happy ending that definitely invites a political reading. The Ninth Heart also features contributions from legendary animator and puppeteer Jan Švankmajer, who brings to life several wonderfully surreal paintings done by his wife Eva for the film’s opening credits.

Nor are these all the riches to be gleaned from this bountiful compilation of arcane rituals and unhallowed grounds. There are another five or six full-length films to explore. Each disc also includes a short film that relates in some more or less obvious way to its accompanying feature, and most of them sport a visual essay or interview that provides much needed context for the often obscure folklore or mythology at work in these films. With volume two of All the Haunts Be Ours, Severin has managed to exceed the embarrassment of riches available in the first volume. Without a doubt, this is one of the most essential Blu-ray releases of the year.

All the Haunts Be Ours: A Compendium of Folk Horror Vol. 2 is now available on Blu-ray.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.