Having established himself with a string of low-budget, transgressive films, New Queer Cinema luminary Gregg Araki expanded his budgetary and artistic palette with his so-called Teen Apocalypse Trilogy, a series of narratively unrelated but thematically linked features about LGBTQ youths living on the margins of a Los Angeles redolent of the desiccated outskirts of the city as seen in Alex Cox’s Repo Man. Like that film, 1993’s Totally F***ed Up, 1995’s The Doom Generation, and 1997’s Nowhere are informed by the legacy and aesthetics of punk, but Araki builds on that foundation with styles drawn from the queer underground, as well as the rise of ’90s alternative music in its myriad forms of noise.

Totally F***ed Up sets the general narrative tone and atmosphere for all three features in the trilogy. Though it does have certain narrative through lines, the most significant of which is telegraphed by an opening image of a newspaper story on high suicide rates among gay youth, the film mostly operates as an episodic glimpse into the lives of a group of LBGTQ friends and lovers who, having been cast out in shame by their flesh and blood, have assembled a makeshift family. Heavily indebted to Jean-Luc Godard’s 1966 masterpiece Masculin Féminin, Araki’s film depicts a crossroads moment for sexuality and culture. In this case, Araki focuses on queer youths coming of age in the wake of the AIDS crisis in the interval between full public crackdown on visible LGBTQ identity and its modern assimilation into the mainstream.

Anchored by confessional interviews conducted among the group by member Tommy (Roko Belic), the film captures a range of opinions and outlooks about queer life from teenagers who refuse to be boxed into any category. Some long for monogamy in relationships while others enjoy being untethered from the standards of heteronormativity. Attitudes range from defiance to self-loathing, often expressed by the same people, and none of the cast more fully embodies the engaging ambiguities of the characters than James Duval, who plays the soft-spoken Andy with a delicate balance of sullen outlook on life and easygoing comfort among his friends. Duval would star in the subsequent films of the trilogy, and his arresting screen presence of realistic adolescent awkwardness and earnest longing is the beating heart of all three films.

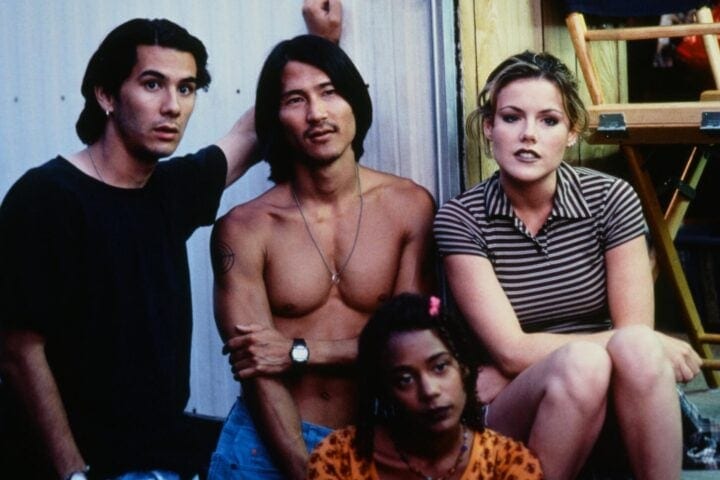

Duval had his work cut out for him bringing that soul to Araki’s next film. Humorously introduced as “a heterosexual movie by Gregg Araki,” The Doom Generation treads the same aesthetically hyperactive and morally castigating waters as Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers. It’s similarly a Bonnie and Clyde tale of two lovers, Amy (Rose McGowan) and Jordan (Duval), who find themselves drawn into a spate of criminal activity on L.A.’s outskirts when they inadvertently fall in with a violent, seductive drifter named Xavier (Jonathon Schaech).

Despite being implicated in a series of assaults and murders, the trio is hardly pursued by police. The city of the film has grown so desensitized to crime that their exploits are just one more grisly update on the nightly news to be discussed with relish by sensationalist anchors. The credits note that The Doom Generation was “filmed on location in hell,” and Araki wastes little time in depicting L.A. as a place where, per the opening needle drop of Nine Inch Nails’s “Heresy” from The Downward Spiral, “God is dead, and no one cares.”

But where, say, Stone’s commentary on amoral media rubs the audience’s noses in their own prurience, Araki’s apocalyptic vision keeps its focus on characters whose nihilistic demeanors crack in the face of a world that reflects their supposed lack of values. McGowan excels as Amy, presenting a façade of total alienation that crumbles over the course of the film to reveal the confused, desperate child beneath the mask. Amy is both disgusted and enthralled by Xavier, who fully embodies the anomie she pretends to, and Duval’s sensitive, sexually fluid Jordan is tugged between both as the group forms a sexually and emotionally codependent unit.

Araki’s first film shot on 35mm, The Doom Generation punches significantly above its weight in terms of maximizing a budget. Using garish color filters and strobes to turn L.A. into a blood-tinged, ever-flickering nightmare, Araki and cinematographer Jim Fealy nonetheless finds ways to give a homey charm to some of the city’s most rundown areas. Abandoned drive-ins and tacky billboards become poetic backdrops to characters struggling to keep their repressed earnestness from surfacing in a mean world, and as the city manifests increasingly hostile threats to their vulnerability, its pockets of safe space become that much more affecting.

The Doom Generation’s ambitious low-budget style marked a turning point for Araki that can be even better appreciated in the dreamscape visuals that pervade Nowhere. Set in a Pop Art-infused L.A. populated by characters who speak almost exclusively in vicious insults and seem to listen to only hi-NRG music, the film at times feels like a glimpse into a world where John Waters had been born 30 years later and had a life-changing teenage exposure to acid house.

Embodying the cultural stasis of its contemporaneous post-grunge, pre-millennium moment, Nowhere oscillates among youths who are compulsive and fueled by constant drug use and sex. Only the occasional indication of romantic jealousy or, more darkly, past abuse hints at the sorrow that all of them desperately hide under narcoticized exteriors.

Nowhere primarily takes place within the bedrooms of its characters, a series of wildly stylized chambers filled with everything from Pop Art polka dots to a mural of James Duval’s Dark in his own room. These personalized domains are shelters from a world that’s still unaccepting of their occupants, but the increasing willingness of the characters to be proudly and unreservedly out brings a glimmer of hope to what’s otherwise a bleak trilogy of films.

“Sometimes I think the only thing keeping us together is a mutual fear of loneliness,” says one character of his emotionally distant boyfriend in Totally F***ed Up, and that mixture of pithy ennui and naked despair typifies Araki’s trilogy. It would be easy at first glance to dismiss these movies as overly confrontational, but Araki’s visual ingenuity on shoestring resources and his overriding interest in the characters’ moments of stripped-down honesty lifts these films above the ironic postmodern aloofness that characterized so much ’90s independent cinema.

Image/Sound

Both The Doom Generation and Nowhere get the full UHD treatment based on 4K restorations, while Totally F***ed Up appears only on 2K Blu-ray. All three transfers are outstanding, boasting stellar grain distribution and stable contrast, while ably highlighting the films’ bold chromaticism. Reds, yellows, and blues radiate intensely against the dilapidated buildings in the L.A. exurbs, which can be seen in all its rusted, sand-coated clarity in these new restorations. The Doom Generation and Nowhere really shine on ultra-hi-def, balancing the occasionally extreme contrasts of blown-out stroboscopic light and total blackness without any visible artifacts. Sound is stable in each movie, filling the channels with Araki’s many soundtrack cues of shoegaze and industrial music without ever obscuring the dialogue or Foley effects.

Extras

Criterion’s box sets are always filled with substantive extras, and the mix of archival and new material here offers a holistic overview of each film in the trilogy. Old DVD commentaries for Totally F***ed Up and The Doom Generation are chummy affairs between Araki and each film’s respective stars, with a particular bonhomie between the director and James Duval. A newly recorded commentary for Nowhere offers a similar mixture of chummy reminiscences and informative details about making such a visually dynamic film on such a low budget. There’s also a new roundtable discussion with Araki and various crew members who worked on the trilogy and helped bring the director’s vision to life, and everyone enthuses about the filmmaker’s ingenious use of a budget and the necessity of limitations to produce great art.

Elsewhere, Araki appears in conversation with Richard Linklater, with the pair musing about their career trajectories, the changing landscape of DIY filmmaking from the celluloid era to the present digital revolution, and the role of music in their respective work (as well as the headaches of licensing songs). The set also comes with archival Q&As between Araki and filmmakers Gus Van Sant and Andrew Ahn that focus more specifically on the director’s place in LGBTQ cinema. Elsewhere, Duval shows off a range of memorabilia from the films that he’s kept in a personal archive, from copies of Araki’s marked-up and doodled-on shooting scripts to the actor’s set photos with cast and crew. A booklet essay by critic Nathan Lee offers an overview of the trilogy’s thematic and stylistic properties and places the movies in the context of the independent cinema and the LGBTQ community of the ‘90s.

Overall

Gregg Araki’s bold, riotous, and incendiary Teen Apocalypse Trilogy gets the Criterion treatment with gorgeous transfers and a trove of great extras.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.

I’ve never hit the ceiling as fast or as much on the day Criterion announced this set and Happiness on the same day. They’re both sitting on my shelf as we speak.