Each of the three films included in Radiance’s Daiei Gothic: Japanese Ghost Stories is based on a classic Japanese tale that’s been adapted to film various times over the past century. This speaks to the remarkably timeless and universal nature of the stories, evoking real-life experiences and themes that are common to humans across time and culture.

The earliest film in the set, Misumi Kenji’s Yotsuya Ghost Story, is based on perhaps the most popular kaidan, or ghost story, in Japan. It’s so popular, in fact, that it was also adapted in 1959 by another filmmaker, Nakagawa Nobuo. While that adaptation, The Ghost of Yotsuya, has been more widely available in the West until now, it’s Misumi’s film that veers more radically from the traditional beats of the kaidan, filling in a tale of good and evil with striking layers of ambiguity and feeling.

Where most film versions of Yotsuya Kaidan involve a husband who’s fully complicit in his wife’s murder, Misumi’s film sees both the downtrodden samurai, Tamiya (Hasegawa Kazuo), and his wife, Oiwa (Nakata Yasuko), as victims of a poisonous plot that will allow Tamiya to marry Oume (Uraji Yôko), the daughter of a local nobleman. Even the specifics of Tamiya and Oume’s affair is rendered opaque here, as Tamiya’s light affections are primarily to earn money and gifts from her, and never appear to cross the line into the outright adulterous.

These narrative and thematic changes turn the first hour of Yotsuya Ghost Story into a pure marital melodrama with more pronounced class conflict, while reserving the bursts of vengeance-laden horror for the final 20 minutes. If the drama of the first two acts is a tad rote, even with the screenplay’s unique spin on the story, the scenes depicting Oume’s eventual revenge from beyond the grave—whether her disfigured face or her hand slowly emerging out of a bucket of water—remain deeply unsettling (and their influence on J-horror is unmistakable).

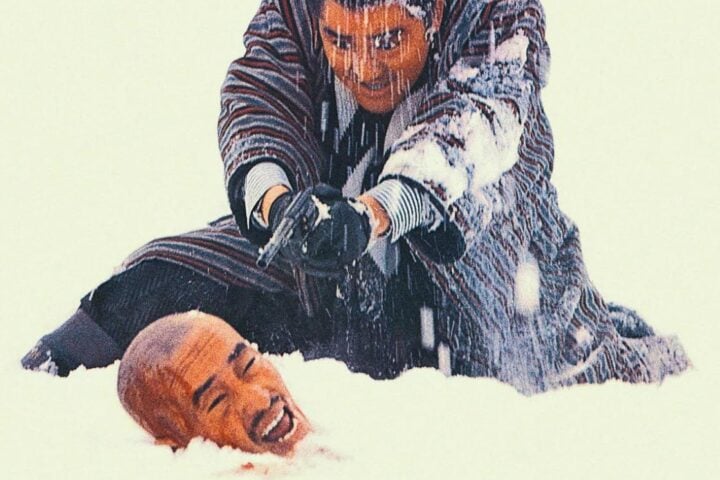

While Yotsuya Ghost Story backloads its horror, Tanaka Tokuzô’s The Snow Woman, from 1968, immediately tightens its grip on the audience, opening with one of its most terrifying scenes. A pair of wood sculptors are waiting in a shack in the woods when Yuki (Fujimura Shiho), the human embodiment of a yuki-onna, or snow woman, visits them and freezes the elder of the two men (Hananuno Tatsuo) to death, while allowing the younger, handsome Yosaku (Ishihama Akira) to continue to live as long as he never speaks of the incident to anyone. Through gorgeous optical and visual effects, well-timed zooms, sharp edits, and extended silences, the film sustains a palpably disorienting atmosphere of dread and unease.

The snow woman has appeared in countless Japanese ghost stories and horror films, most famously the “Woman in the Snow” segment in Kobayashi Masaki’s 1965 masterpiece Kwaidan. And while Tanaka’s film doesn’t engage in the eye-popping, psychedelic splendor as Kobayashi’s take on the tale, it’s quite visually striking in its own right and fleshes out the dramatic and emotional nuances of the relationship that develops between Yosaku and Yuki.

For as relentlessly unsettling and creepy as The Snow Woman is, it’s also quite romantic, pitting Yosaku and Yuki against a world that seems to be conspiring to break them apart. It’s as much a tragic love story as it is a horror film, and its final few scenes are both heart-wrenching and haunting, tinged with a melancholy vengeance that’s distinctly Japanese.

Obsessive love between man and ghost is also of central importance in Yamamoto Satsuo’s 1968 film The Bride from Hades, which follows a young teacher, Shinzaburo (Hongô Kôjirô), who’s disowned by his well-respected samurai family after refusing to marry his brother’s widow (Uda Atsumi). The ghost, Otsuyo (Akaza Miyoko), who visits him after he performs a small but chivalrous act, relates a tragic tale of her own father abandoning her, connecting the pair over the paternal failures and class conflicts that left them both as social outcasts.

Yamamoto casts a skeptical eye on the samurai class and codes of honor, as well as on many of the fearful, greedy townspeople, who are presented as more destructive than Otsuyo and her maid, Oyone (Michiko Otsuka). Where previous versions of the story have focused more on Otsuyo’s desperation to find a husband before the end of the Obon festival, when she would be forced to return to the afterlife, Yamamoto’s film sympathizes with her plight.

Despite the deep empathy at the core of The Bride from Hades, its romanticism is still rendered with an eye for the uncanny and disconcerting. The film abounds in gorgeously eerie moments, from Otsuyo and Oyone floating and gliding through town to Shinzaburo and Otsuyo’s first romantic tryst, in which the latter’s skin appears translucent, revealing a glowing skeleton beneath. Even its ostensibly happy ending will send chills down your spine—a perfect example of the kaidan’s ability to meld the romantic and erotic with the ghastly and otherworldly.

Image/Sound

Each of the three films included in this terrific set have been mastered from new 4K restorations, and the results are uniformly great. Reds, blues, and greens really pop in the brighter scenes, while the strong contrast ratio allows the more subtle color variations in the darker, more horrific scenes to be fully appreciated. The images are consistently sharp and rich in detail, while the grain is tight and even throughout and all signs of damage have been entirely cleaned up. On the audio front, the 24-bit mono audio tracks nicely handle the eerie sounds of howling winds and crackling fires, as well as the moody scores of all three films.

Extras

Radiance’s extras for this set do a fantastic job of placing Daiei Film’s output from the late 1950s to the late ’60s into the context of Japanese cinema of the era. In a new interview, J-horror master Kurosawa Kiyoshi discusses why Yotsuya Ghost Story is his favorite film adaptation of the Yotsuya Kaidan and how it differs from other versions. The first disc also includes a wonderful video essay by film historian Hirano Kyoko that delves much deeper into the differences between the various adaptations of the kaidan.

On the disc devoted to The Snow Woman, filmmaker Masayuki Ochiai (Shutter) offers a strong analysis of the supernatural creatures known as yôkai in Japan. He particularly stresses the differences between yôkai, who can be kind and live alongside humans, and ghosts, who tend to return for reasons of revenge. Elsewhere, Lafcadio Hearn biographer Paul Murray’s visual essay on the writer serves as a nice primer on his life and work, touching on his Buddhism, his immersion in Japanese culture, and the gothic inflections of his writing.

The last disc includes a commentary track by author Jasper Sharp about The Bride of Hades. Sharp covers the film’s special effects, its influence on J-horror, and the ’60s horror boom. He also goes on some interesting detours, like a discussion of the early history of 70mm film in Japan. The last on-disc extra features Hiroshima Takahashi, the screenwriter of Ringu, talking about the history of the story on which The Bride of Hades was based.

Rounding out the package, which features original and newly commissioned artwork by Filippo Di Battista, is an 80-page booklet that includes essays by Tom Mes and Zack Davisson that provide comprehensive overviews of Daiei Film’s illustrious filmmaking history, three archival reviews, and a series of ghost stories by Lafcadio Hearn with introductions by Paul Murray.

Overall

Radiance’s tremendous box set highlights three lesser-known gems of mid-century Japanese horror, offering a strong slate of extras that attest to their importance.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.