Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg’s Performance was shot in July 1968, but its release was postponed by a skittish Warner Bros. until August 1970. The timing couldn’t have been better, since the film not only perfectly encapsulates Swinging London’s faith in “sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll” but also effectively hammers the last nail in the counterculture’s coffin. As a sort of epilogue to the Rolling Stones’s disastrous concert at Altamont, Performance illustrates precisely what can happen in the void left gaping open when performers stop performing.

Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg’s Performance was shot in July 1968, but its release was postponed by a skittish Warner Bros. until August 1970. The timing couldn’t have been better, since the film not only perfectly encapsulates Swinging London’s faith in “sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll” but also effectively hammers the last nail in the counterculture’s coffin. As a sort of epilogue to the Rolling Stones’s disastrous concert at Altamont, Performance illustrates precisely what can happen in the void left gaping open when performers stop performing.

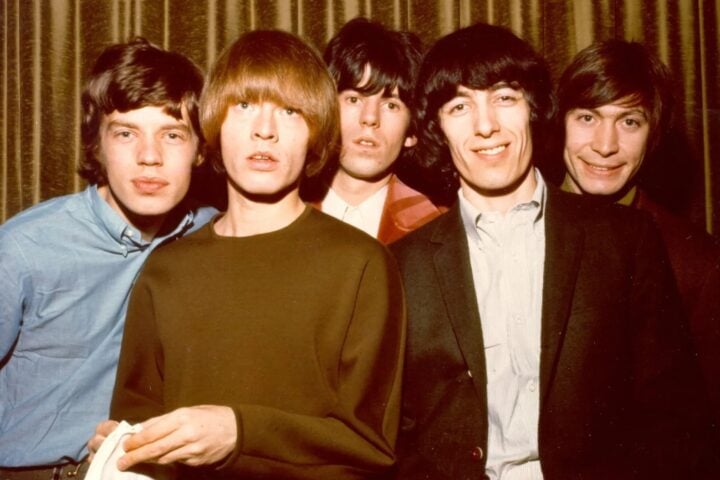

The film’s title is aptly overdetermined. Reclusive rock star Turner (Mick Jagger) is obviously one kind of performer. But performer, in British slang, also refers to mobsters like Chas (James Fox). In the film, the worlds that these two men inhabit collide and entwine in fascinating fashion. Over the course of the first half, which is dedicated to delineating the volatile Chas’s place in the London underworld, we witness several occasions where a larger outfit absorbs a smaller one—whether in the realm of so-called legitimate business or the criminal demimonde—and we’re told that what’s happening isn’t a takeover but a merger. Nothing hostile—just business as usual.

The idea of bringing two elements together in a deliberately jarring manner is embodied in editor Frank Mazzola’s frequent use of flash cuts between disparate events. (Mazzola would go on to collaborate with Cammell on all of his subsequent films.) Performance is one of the greatest British gangster films of all time, a clear precursor to the chilly brutality of Mike Hodges’s Get Carter and John Mackenzie’s The Long Good Friday. But once Chas turns up at Turner’s digs on Powis Square, seeking some much needed shelter, the film’s chilliness gives way to something richer and stranger. Performer descends into a druggy miasma of shared baths, fluorescent light shows, and discordant sounds from a newfangled Moog synthesizer.

The film’s second half explores a more existential definition of performance. If, per Jean-Paul Sartre, you’re the sum of your actions, what happens when you start to act like someone else? If there’s no essential you, then your personality is merely a persona, nothing more than a mask that can be doffed and donned at will. Existence is inherently performative.

In an effort to break through his carapace of identity, Turner and his amorous companions, Pherber (Anita Pallenberg) and Lucy (Michèle Breton), put Chas through the existential wringer, feeding him ego-destroying magic mushrooms and poking fun at his sense of self, especially his hidebound masculinity. Chas might start out as the hard, cold bullet he claims to be, but, by film’s end, he’s as glam androgynous as Turner. In fact, he just might be Turner.

Turner has lost his “demon”—his inspiration, his raison d’être. Performance used to bring him close to the ecstasy (“standing outside of yourself”) that can be found in Antonin Artaud’s writings. Turner paraphrases Artaud’s notion of the Theater of Cruelty when he tells Chas, “The only performance that makes it, that really makes it, that makes it all the way, is the one that achieves madness.” Cut off from that transcendence, all that’s left for Turner is Chas’s bullet.

As the bullet bores through Turner’s skull, we see a portrait of the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges. Turner had earlier read a few lines from Borges’s story “The South,” which concerns a dying man’s vision of a death more noble than the one he faces. In the end, it’s not clear whether Turner achieves a noble death, or even who exactly dies. Like all the best mindfuck films, Performance leaves it up to the viewer. Beyond that, the film remains a beguiling time capsule—sensual, cerebral, both ode to and threnody for a very specific time and place.

Image/Sound

Criterion presents Performance in a spectacular transfer—sourced from a 35mm original camera negative and (for one section) a 35mm internegative—that represents a significant improvement over the version on Warner’s earlier Blu-ray in pretty much every department. Black levels are deeper, delineation sharper, and colors far more vibrant, especially those psychedelic green, purple, and gold highlights when the action moves to Turner’s domain.

On the audio front, Criterion fixes issues that had been found on earlier DVD and Blu-ray releases, whose audio tracks alternated between the original recorded sound and a post-production dub meant to make the thick Cockney accent of the Harry Flowers character more accessible to American audiences. The sturdy LPCM mono mix also reinstates Turner’s missing line: “Here’s to Old England!” The track admirably conveys the eerie Moog noodling by composer Jack Nitsche, Mick Jagger’s indelible “Memo from Turner,” Merry Clayton’s soulful ululations, and the jazzy spoken-word panegyrics delivered by the Last Poets.

Extras

Donald Cammell: The Ultimate Performance is an excellent profile of Cammell that naturally devotes a large section to the making of Performance. It also touches on Cammell’s early days as a portrait painter in London and Paris, his move into film as screenwriter on Duffy, appearance in Kenneth Anger’s Lucifer Rising, difficulties with the Hollywood studio system on subsequent films (Demon Seed, White of the Eye, and The Wild Side), and tragic death by his own hand.

The making-of documentary “Influence and Controversy” does a solid job of letting its talking heads, including many of the cast and crew, provide insight into the filmmaking process. This material is bolstered by another half-hour’s worth of outtakes from the documentary.

Elsewhere, we get a fascinating visual essay on David Litvinoff, credited as Performance’s technical advisor, who provided a real-life bridge between London’s underworld and celebrity cultures. A brief program illustrates the differently dubbed versions of the film in a side-by-side comparison. Another short archival piece shows Jagger on the set of the film working on the “Memo from Turner” sequence. Lastly, the disc’s illustrated booklet contains an essay by film critic Ryan Gibney on Performance as a radical new kind of filmmaking and a 1995 article by scholar Peter Wollen on the film’s themes of decadence and death.

Overall

One of the great British cult films, Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg’s Performance gets a superlative 4K transfer and a satisfying slate of supplements.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.