From the moment Jean-Luc Godard returned to commercial cinema with his self-proclaimed “second first film” Every Man for Himself, he devoted himself to crafting a kind of holistic film, one rebuilt from the supposed “end of cinema” represented by his caustic 1967 feature Weekend. It was a goal he pursued until the end of his life, constantly revising his methods with new editing and video technology while finding new ways to illustrate the intersections of moviemaking, artistic representation, and the political histories that art both reveals and obscures. His first major summary of this method was 1987’s King Lear, a nominal treatment of Shakespeare’s tragedy that’s a total deconstruction of the prospect of adaptation.

From the moment Jean-Luc Godard returned to commercial cinema with his self-proclaimed “second first film” Every Man for Himself, he devoted himself to crafting a kind of holistic film, one rebuilt from the supposed “end of cinema” represented by his caustic 1967 feature Weekend. It was a goal he pursued until the end of his life, constantly revising his methods with new editing and video technology while finding new ways to illustrate the intersections of moviemaking, artistic representation, and the political histories that art both reveals and obscures. His first major summary of this method was 1987’s King Lear, a nominal treatment of Shakespeare’s tragedy that’s a total deconstruction of the prospect of adaptation.

Godard’s avant-garde approach and totalizing ambitions are obvious from the outset. The first thing we hear is a taped phone call from producer Menahem Colan berating Godard for taking too long with the project and demanding a cut in time for that year’s Cannes festival. Its first images (discounting fragmentary title cards) are of the film’s original screenwriter, the author Norman Mailer, reviewing his screenplay of a gangster version of King Lear with his daughter, Kate, before his own frustrations with the director lead him to quit the project.

The film proper takes place in an alternate timeline where the Chernobyl disaster affected the entire world, though in the end everything and everyone survived save art and culture, which in Godard’s view is the same as saying that nothing survived. “Nothing,” indeed, becomes the crux by which the film approaches King Lear, fixating on the word that Cordelia utters to her monarch father in the first act when she refuses to ply him with flattery in order to secure her inheritance. Left with “nothing” of the original play, Shakespeare’s last living descendant, the preposterously named William Shakespeare Junior the Fifth (Peter Sellars), must reconstruct it, in part, by eavesdropping on an aging gangster, Don Learo (Burgess Meredith), and his daughter, Cordelia (Molly Ringwald), having conversations that recall moments from the play.

Described in an intertitle as “an approach” to the play, Will Jr.’s reconstruction deviates sharply from the original text, and in the process Godard aestheticizes the act of adaptation. A recurring intertitle that breaks down Cordelia’s “Nothing” into “No Thing” is classic Godardian wordplay, but it also captures in text form the same kind of careful examination of meter and emphasis that actors bring to bear on Shakespeare to find new angles into the material.

The startlingly tacit implication of incest between Learo and Cordelia likewise smacks of the kind of bold interpretation that artists have employed when adapting Shakespeare’s work in order to ensure its contemporaneity. Similarly, the rapid accumulation of Learo and Cordelia’s approximations of King Lear’s dialogue, actual lines from the play, and a mix of quotes from other Shakespeare plays and sonnets captures the telltale voice of the author’s prose and poetry.

Will Jr. slowly recreates King Lear by mixing the father and daughter’s interactions along with snatches of the original play’s dialogue that he remembers, as well as lines from other Shakespeare plays and sonnets. This freewheeling mixture of quotations results in more and more divergences from the source that tacitly acknowledge that any act of adaptation from one art form to another will always lose and gain certain aspects of the original. Even an aspect of the film’s incredibly dense stereo soundtrack—that of the frequent intrusion of the sounds of lapping waves and screeching shore birds from around the Lake Geneva shooting location—feels Shakespearean, albeit far more suited to an adaptation of The Tempest than King Lear.

Elsewhere, that soundtrack is part of a larger tapestry of overlapped noises and images that expand the quotations outward from Shakespeare to encompass things like treatises on the concept of imagery by Robert Bresson and the surrealist poet Pierre Reverdy, speed-manipulated recordings of Beethoven’s string quartets, and various film stills and paintings. In forging a new version of a single play, the film keeps flitting between more and more fragments of inspiration until it becomes an artistic variation of Carl Sagan’s old quip “if you wish to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first invent the universe.”

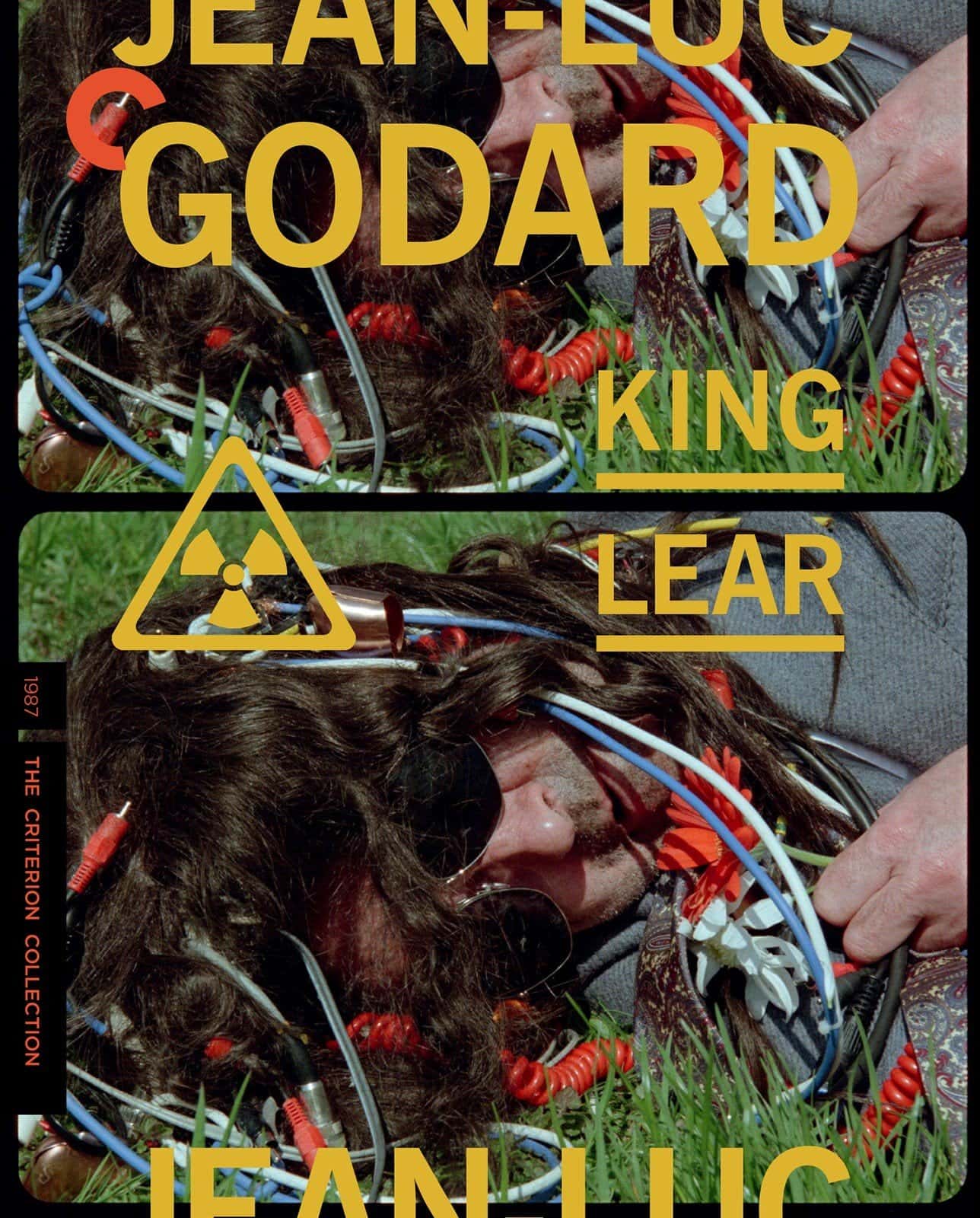

Besides Godard’s own subsequent work, perhaps King Lear’s best point of comparison is David Lynch’s Inland Empire, another insoluble work that both pillories the pitfalls of commercial film production and reaffirms the possibility of art to emerge from a compromised and exploited form. Godard himself appears throughout the movie as “Pluggy,” an eccentric figure so named for the various A/V cables that snake out of the top of his head like cyberpunk dreadlocks. An abstruse guru, Pluggy guides Will Jr. toward a higher understanding of his responsibility of putting art back into the world and mostly pontificates about the magic of montage.

Toward the end of Godard’s film, Pluggy effectively rediscovers cinema and transcends its limits as a plastic reflection of reality by using reversed footage of a plucked flower to “re-grow” the plant. For an artist who’s usually associated with his pessimism, Godard uses King Lear to lay most bare the underlying thesis of his late period: that cinema, whether or not it’s actually dead, can be reborn in ways that are new, invigorating, and beneficial to life itself.

Image/Sound

Outside of rare retrospective screenings, for decades now King Lear has largely been seen, if at all, via low-quality bootlegs. Criterion’s transfer, sourced from a 2K restoration, is a revelation. The painterly beauty of Sophie Maintigneux’s cinematography and its heavy emphasis on naturalistic tones of blues and greens can finally be appreciated, and scenes in dim interiors sport deep black levels with no visible crushing or halo artifacts. Detail is fine enough to make out the faint signs of photo reproduction on the film stills and painting scans woven into the montage. Equally impressive is the soundtrack, which flawlessly renders the stereo track of overlapping dialogue, needle drops and ambient sound. The soundtrack is as blatantly artificial as it is immersively impressionistic, and it’s overwhelming to hear it in its full clarity.

Extras

New Yorker critic Richard Brody, likely the film’s biggest champion in the English-speaking world, contributes both an interview and the booklet essay for Criterion’s release. In both, he makes the case for the film as a Gesamtkunstwerk of Godard’s career while also offering ample insight into the project’s convoluted and enervating production. Brody even obliquely features in the interview with Molly Ringwald, who reminisces about how baffled she was on the set of King Lear and how she came to appreciate the film years later when reading Brody’s Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard. Also interviewed is Peter Sellars, who recalls in depth the strangeness of the production but clearly prides having participated in the project. The disc also comes with audio of a press conference with Godard at its Cannes premiere, in which he’s his usual evasive, irascible, yet always entertaining self.

Overall

Jean-Luc Godard’s long-neglected masterpiece at last receives a proper video release in a stunning A/V transfer that primes the film for overdue rediscovery.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.