Just as in his previous feature, Chained for Life, writer-director Aaron Schimberg’s A Different Man throws away the kid gloves to unpack the complicated ways in which contemporary society responds to disability. Eschewing the polemical, the film’s self-reflexive dismantling of victimhood and villainy tropes functions like a puzzle in which the ways in which the viewer responds to the central character provide the final piece.

A Different Man pitilessly plunges into the insecurities gnawing away at Edward (Sebastian Stan), a New York actor struggling to land jobs that don’t center his facial neurofibromatosis. This disfiguring condition pigeonholes him in dementedly cheerful PSA videos about how to accommodate disabled colleagues in the workplace. Schimberg never clarifies if these demoralizing projects create Edward’s low self-worth or merely feed his conception of it. The film refuses to excavate a psychological silver bullet that can explain the character’s behavior.

If anything, A Different Man sides against cultural determinism to help counterbalance hollow narratives about disability. The film persuasively rejects the patronizing premise of the “makeover” movie and reality TV show, which suggest that some secret virtue of “inner beauty” can be revealed were a person to revamp their outer appearance. There’s no secret, redemptive nobility to Edward’s suffering. Though cruel, caustic ironies define his life, he slowly morphs into a fearsome figure not because of how he looks but because of how he acts.

Edward’s ownership over his fate becomes undeniable at the film’s midpoint, when an experimental procedure to which he submits himself vanquishes the tumors from his face. Given the choice to renegotiate this altered appearance with others’ perceptions of his old self or reinvent himself, he opts for the latter in the persona of Guy. He’s rendered so unrecognizable to his neighbors that they’re easily convinced by his claim that Edward died by suicide.

Though Mike Marino’s elaborate prosthetic design effectively disguises Sebastian Stan’s appearance when acting as Edward, little else about the alter ego of Guy exudes the power of movie-star charisma. As he’s receiving oral sex in a public bathroom, he fixates not on the act itself but on his image in the mirror—clearly staring in disbelief that anyone might fashion him an object of desire. Stan’s bone-deep commitment to embodying the character truly shines as the man tries to unlearn the physical manifestations of psychological insecurity. Even something as simple as entering a room becomes a powerful articulation of how the character feels the tacit need to request permission before taking up space. A subtle, tentative crouch speaks volumes more than the traditionally overwrought cinematic interpretations of disability.

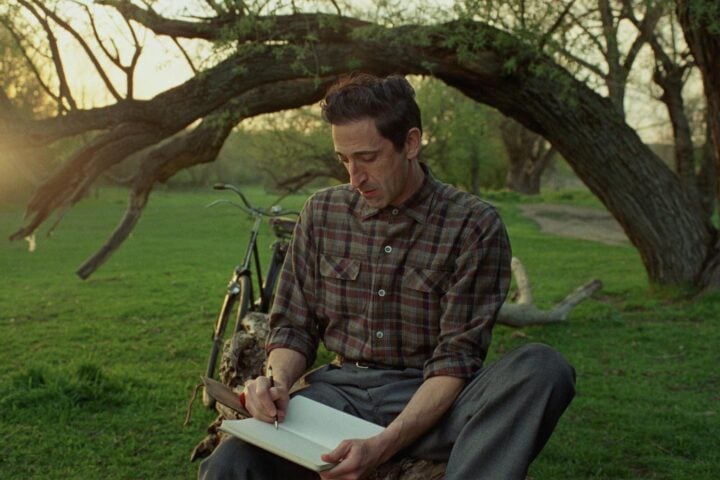

Guy’s initial foray into the transactional world of real estate, which allows him to glide by on his dashing good looks to an extent that surprises even him, helps him get past such qualms in the business world. But this professional stability begins to unravel as he passes a small community theater and begins to feel called back to acting. Soon, a detour into the casting process of a new play sets up his most challenging role yet: playing a fictionalized version of himself.

Edward happens to stumble upon his kindly former neighbor Ingrid (Renate Reinsve) in the early stages of adapting his life and assumed death into the tidy story structure of a theatrical tragedy. Despite her initial qualms in casting someone without a visible disability, she unwittingly casts the subject of her work to reinterpret his own life. But Guy struggles to access the heart of the character, a woe that aggravates him especially because it highlights his inability to resolve his lingering identity crisis. The process nearly drives the protagonist insane as he unconvincingly tries to imitate what he can no longer inhabit.

The difficulty of the task only deepens when the similarly neurofibromatosis-afflicted Oswald (Adam Pearson), a man whose condition has not addled him with any social anxieties, stumbles into rehearsals. He’s a walking rejoinder to simplistic ideas surrounding disability as a definitional element of life for those affected by it. Oswald’s pleasant presence challenges the very assumptions of Ingrid’s play as well as Edward’s self-loathing.

The dialogue Oswald inspires by his participation in the production echoes loudly, not only as an indictment of the play, but also as the essence of representation at large. Schimberg grants plenty of space for Edward to seethe in resentment over what this emerging foil epitomizes. Stan sublimely seizes these moments to demonstrate that, unlike his character, he’s comfortably uncomfortable stewing in the contradictory nature of both acting and being. He and Schimberg are fearless in their embrace of a disabled antihero whose dyspeptic disposition arises from bitter disappointment that his transformation came with no catharsis.

Yet for all the restless inquisition in his script, Schimberg also proves capable of compactly distilling his ideas into searing single shots. Take a moment deep in the film when Guy brings out a mask of his old visage during pre-coital roleplay. At his partner’s insistence, he stands full-frontal naked before her—and the camera—before pulling the Edward mask over his face. It’s at once a revealing and concealing image that, like the film in which it lives, collapses any notion that concepts of authenticity and artificiality in the self can be considered independently. Every neat division eventually folds in on itself in his dense, dynamic discourse on disability.

These bold, often brutal declarations of duality are baked into the reflective structure of the multilayered A Different Man. The darkly humorous undoing of Edward illustrates Karl Marx’s maxim that “history repeats itself, first as a tragedy, second as a farce.” This journey might be punishing for the character, but it’s profound for the audience. The film’s overarching dramatic irony leaves one to ponder the deliberately discomfiting question of whether it’s possible to extricate the experience of disability from the way spectators define its essence.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.