“Never in any part of my imagination would I have thought myself to be a representative of anything,” claimed Matthew Rankin, the co-writer and director of Universal Language, when asked about his film representing Canada in the Oscar race for best international feature. That expression didn’t indicate any doubts about the quality of the work. Rather, it was a nod to the irony of a film that deconstructs the idea of nations and borders being selected to compete in a race whose parameters were defined by those exact parameters.

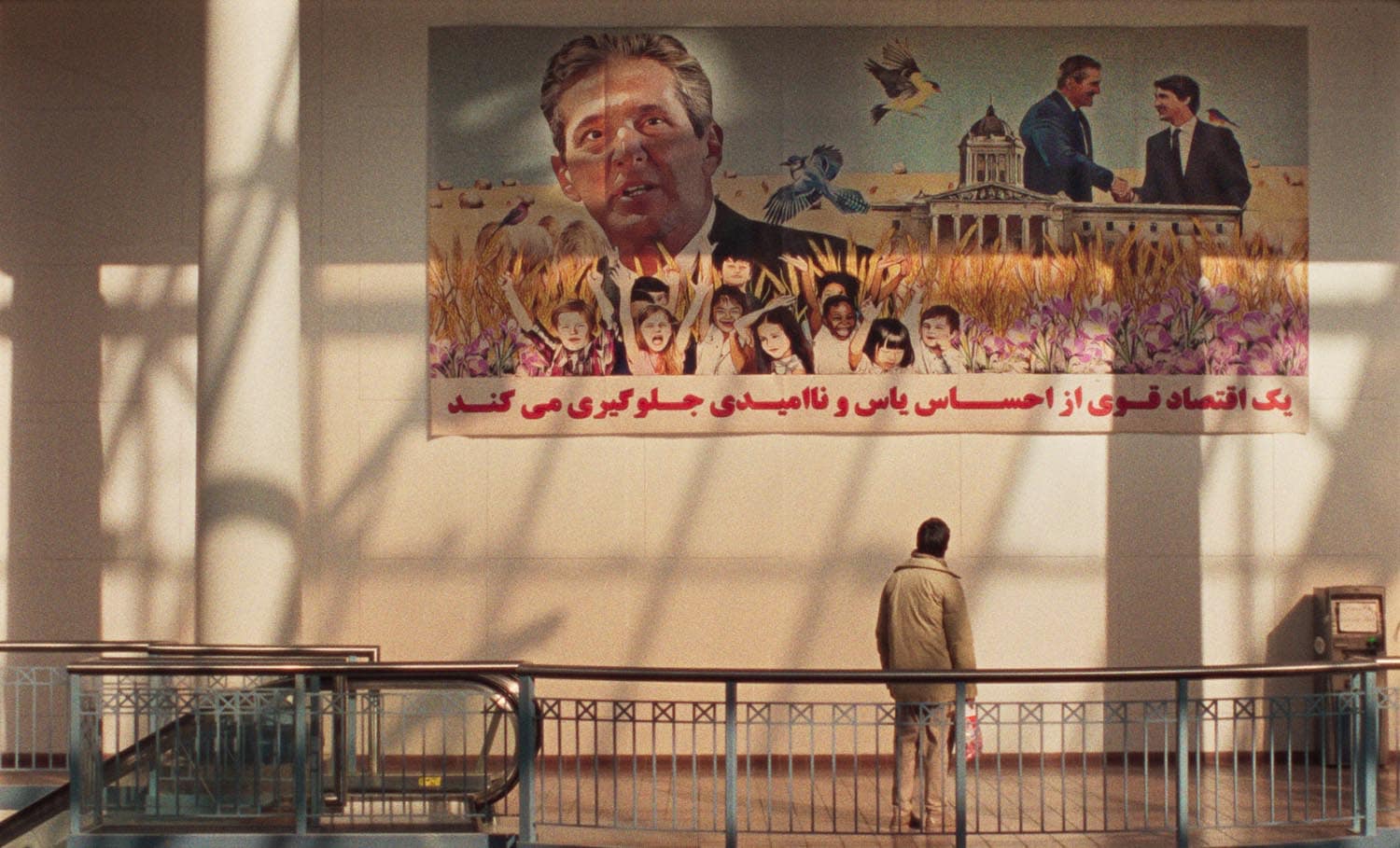

While Universal Language might have missed an Oscar nomination, Rankin’s mode of empathetic and creative intercultural engagement is likelier to stand the test of time than the category’s putative frontrunner. His film blends the deadpan humor of Aki Kaurismäki with the formal playfulness of Abbas Kiarostami as it follows three stories that converge in a wintry setting that seems to fuse Tehran and Winnipeg. Despite its visual austerity, it feels like anything can happen inside the wide, welcoming world of Rankin’s imagination.

Of the three seemingly unconnected stories that make up the film, the most straightforward concerns two children, Negin and Nazgol (Saba Vahedyousefi and Rojina Esmaelli), and their effort to claim a banknote frozen under the ice. Meanwhile, the fictionalized version of himself that Rankin plays follows a more discursive trajectory as he meanders his way from a dead-end bureaucratic job back toward his family. All the while, a tour guide (Pirouz Nemati) leading a group through the film’s parallel-universe Canada manages to disorient as much as he informs.

Each branch of Universal Language contributes to its overarching surrealistic and sardonic vision, but the film is more than merely a collection of absurdist vignettes. Rankin ties everything together through a sincerity that might seem to run counter to the film’s devotion to artifice. Paradoxically, the specific details of his invented reality all work in service of an engagement with wider shared notions of what it means to find home.

I caught up with Rankin over a long lunch just before he premiered the film at 2024’s New York Film Festival. Over lemon meringue pie, he described Universal Language from its earliest conceptual idea down to the execution of dealing with a turkey that went AWOL from set. The conversation also touched on how he developed his visual approach to shooting what he calls the peripheral gaze of the film, why he rejects the idea that fakeness in cinema is inherently bad, and where his collaborations informed the cross-cultural exchange of the film.

I couldn’t help but notice all the brutalist buildings across Winnipeg that you capture in Universal Language. How much do you feel those structures reflect or shape the character of the people who inhabit them?

On one level, it emerges organically from the material. When I went to Tehran for the first time, I was really struck by how much the buildings [there] reminded me of the buildings in Winnipeg where I grew up. There was a strange kind of architectural echo in these beige, brutalist monuments. My collaborators, Ila Firouzabadi Pirouz Nemati, had a similar experience of recognizing Tehran in a city they had never been to when they went to Winnipeg. The idea of a very brutalist Winnipeg was going to be the point of crossfade between the two cities. Winnipeg does this a lot. It’s a city that’s played Houston, in fact! It’s played Dallas, Chicago, Minneapolis, and there’s one movie in which it plays Tokyo. Insane!

The idea of a city playing another city was my tuning fork. Part of the undertaking is to seek out the poetry in the blandest possible imagery and to fill in these boring buildings with the same love, attention, and sense of the divine [with which] Terence Malick would fill in the sunrise. The film also plays with the ideas of proximity and distance, so I knew I wanted to do a lot of wide shots. Sometimes, you don’t see the characters at all. [Rather], you’re seeing the building in which they’re having a conversation, which is also a very Iranian trope.

Do you find brutalist architecture beautiful?

Yeah, I find it very beautiful! I think it’s utterly ecstatic. There have been a few people who’ve made these offhanded wisecracks about how the movie will do nothing for Winnipeg’s tourism ambitions, but I reject that. I don’t know, that’s a place I’d like to go! I love Soviet brutalism, especially all those former Yugoslavian brutalist monuments. And as far as the city has been represented in cinema, it’s either playing another city or it’s ruin porn that makes Winnipeg look like Detroit. And a lot of Christmas movies are filming Winnipeg, so it’s trapped in this perpetual Hallmark Christmas time. But I had never seen Winnipeg film in this way, and that was part of what I wanted to do: to really put this mid-century brutalist Winnipeg on display.

The film opens with a title card paying homage to Iranian cinema, citing this is a product of the Winnipeg Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young People. I know it’s cheeky, but do you hope the film actually can prove instructive to young viewers for those purposes?

Sure! Kanoon is the name of that institute [Center for the Intellectual Development of Child and Adolescent] in Iran that produced many of the great Iranian classics, and also a lot of animation. It reminded me of the National Film Board of Canada. It was [based on] this idea that culture serves a public good, so there are a lot of good intentions behind a lot of the work. But a lot of radical artists found their footing in there, and all manner of great early masterworks of Iranian cinema moved through that studio. We wanted that to be like the entry point: Here’s your frame of reference, or a door through which you can walk. This is how you’ll find your path.

Do you see your approach to time in the film as a refraction of the past, a reflection of the present, a hope for the future? A combination? Something else entirely?

It’s told in a fragmented way, and that’s related to this idea of the peripheral gaze. In Western cinema, writ large, we focus on wherever the action is. The camera follows whoever is speaking or acting like a hockey game follows the puck. But a lot of these Iranian films found their influence in Italian neorealism [and] the idea that what’s next to the action is maybe just as interesting as the action itself. By not showing the most dramatic event, what questions does that leave the audience? Seeing the person listening rather than the person speaking, does this not raise new questions about how we experience movies and how we encounter a story? We’re going here on this linear path, and then suddenly we’re over there. It zigzags around. Of course, the movie is about finding your way home, and this is a circuitous path.

How do you go about developing the evolving visual language within the film? Is it as meticulously planned down to the edit as it is with the shot composition?

Some of them were very calculated. There’s one shot of the tour group beginning their 30 minutes of silence, and the camera leaves them to catch up with this meandering car coming to its destination. That, of course, is a very calculated shot and very tricky to get. It required a lot of math and cues. But we did like to keep a lot of space open to whatever was happening. In part, when you’re shooting with kids and a turkey, you have to be open to a certain amount of chaos. Sometimes, the camera captured elements separately so that the actors could express themselves more fully. There was certainly a large amount of openness to chaos, but always with this tuning fork that there was a way of filming. It still had to fit into the grammar of the whole.

How does that also translate into the way you directed the performances?

It’s an interesting thing about tone. I feel like the script itself tells you something about what kind of tone it is, and then people either get that, or they don’t. You try it out in rehearsal, but the lines are written in such a way that either you can tap into that, or you can’t. The absurdity of the film was something we were assessing in the casting process. The ideal is that not only do they get it, but they’re also enlivened by it. They can express themselves fully through it. And to a large extent, we cast our friends, so they understood what’s funny to us.

The film is chock full of visual gags and comedy bits. Where do those originate, and how do you see them through from conception to choreography?

It depends on the bit. The children’s lineup for the swing set, for example, was drawn from my own childhood. I went to this school where there was only one swing set, and we all had to share it, which was kind of absurd. It was just about practicing it until it reached this Bressonian degree of meaninglessness. You work it until you feel it.

The turkey is certainly a whole other kettle of fish. There’s something innately funny about a turkey, and working with a real turkey, there are all manner of challenges. We wanted this turkey to sit next to our friend who plays a passenger on the bus, and we were shooting in the springtime. The turkey wrangler said there was a strong possibility the turkey might try to mate with her! So we put this like a plexiglass barrier between them so that it wouldn’t mate with her. It was the strangest day of filming of my entire life. You never know how this is gonna go; it could be a total disaster. But it worked out! It was a wild turkey, but if you’ve ever watched the president pardon a turkey, you know that a turkey can be coaxed into a calm little space even with lots of people looking at it. Some of these things, you figure out in the moment. It’s a lot of actual reaction. The turkey escaped at one point. It just went AWOL, in fact. We were shooting a snow dump at one point, which is enormous: 300 feet tall, two kilometers wide. It just scuttled up to the top of this, and we couldn’t get him down. The next morning, he was arrested. But then, he was brought back and put in, I think, a very soulful performance.

How do you balance artificial appearances and authentic emotions? These are so often foiled against one another, but they coexist beautifully in your work.

It comes down to intuition. The story comes from my own life, my family history, my memories, and my dreams. It’s a lot of synthesis between the ironic and the very earnest. Too much of one or the other, and the whole thing collapses. You’re walking a tightrope. That was definitely the ambition going in. I’m a big believer that cinema is artifice. Even when we speak of authenticity in cinema, we’re speaking of something fundamentally fake. Embracing the artifices can open up new doors in expression. To this point in cinema history, to a certain extent, the ambition of cinema has been credibility. We’re creating a simulacrum, and anything that reminds us that it’s fake is bad. A continuity error is bad. A stilted performance is bad. You get a period detail wrong, and someone writes you an email titled “YOU IDIOT.”

That’s all fair because I think a lot of people go into movies still with the expectation that they’re supposed to be real. You’re supposed to forget that it’s fake. But a big Iranian concern in a lot of those films the movie is referencing—the Koker trilogy, Close-Up, A Moment of Innocence, the whole Jafar Panahi canon—has intense skepticism about capacity [for realism]. It’s a poetic and artificial undertaking, and the idea is that it creates a new emotion. But it’s fake! That’s a line that I find interesting, when you’re confronted by how un-credible and not real it is.

We have this change of cast in the last section of the movie, which people have described as a spiritual transfer, which [it is]. It’s artifice, but it contains poetic property. As cinema goes on, I think it’s something that we will explore more. If we’re looking for simulacra, there’s other stuff that can do that better than cinema. So what does that mean for cinema? To me, I think it means we will go into more abstract territory, just like painting changed with photography.

You’ve said that you wanted the film to be a reflection of what was going on in your life as you were making it. How do you go about folding that into the artifice?

I go on and on about artifice, but the point is still to create something real. The idea is to look at the world in a way we haven’t looked at it before, but still to create real emotions. This movie is processing a lot of things that were consuming my thoughts while we were making it, and that all comes from a real place. They’re given expression in this film. It’s a very personal film, and very different from the last one. The form is changing as I change.

When does sound start to come into play? Most people tend to fixate on the visual over the aural, but from the wheelchair noises to the turkey calls, there’s a lot of sly wit taking place in the soundscape.

I work with a brilliant sound designer named Sacha Ratcliffe, who also does soundtracks. She has her own artistic sound practice and is motivated to go into the abstract spaces. In the sound, we tried to cast this peripheral gaze. Sometimes, the image stays static but the sound moves across a wall. I remember when we were mixing, I’d be like, “Is there any rule to this?” In the first shot, we’re outside looking in, and the sound moves inside as the camera stays out. Then, it comes back outside when this little boy walks in. We were like, “Does the sound inside have to fade away when we go back outside? No, it can be both!” This was a process of discovery for us with a lot of experimentation. Even just managing this weeping man in this cubicle while this conversation is happening, it’s a very delicate operation to get those two sounds happening simultaneously but not competing with each other to create a comical, disrupting logic of space.

You brought Canadian-Iranian communities into the creation process of the film. What did they add to the film that you didn’t anticipate?

First and foremost, it would be the Iranian community of Montreal. We shot most of the film in Montreal, but we did shoot for about a week in Winnipeg. There were Iranians in Winnipeg who were part of that shoot, in front of and also behind the camera. But I would say, overwhelmingly, it was Montrealers, particularly my co-writers Ila Firouzabadi and Pirouz Nemati who also acted in the film and were executive producers of it. It was a very loose process, all about measuring the degree of merging. There’s no element of Iranian culture in the movie that isn’t also merged with some element of Winnipeg. The idea was to keep the two almost indistinguishable from each other, as much as we might imagine a great distance between them. There was this overlap and cross-pollination, so it’s in two different places at once. Maybe it’s Tehran; maybe it’s Winnipeg. Maybe it’s Tehran doing a bad imitation of Winnipeg; maybe it’s Winnipeg doing a bad imitation of Tehran. It was all about walking that fine line, and that was something we’re talking about every day on every level- particularly in the art department and the script.

What are your thoughts on universality now that you’ve made the film? What unites us across cultures but doesn’t flatten out the things that make us unique?

I feel like we’re living in a time of very great suspicion, and there are a lot of binaries that have shot up around us. Culture, politics, gender, geography…great Berlin walls have shot up. This movie is a very intercultural one, and that’s an unusual space. It’s about having no borders and creating something new. It’s not an Iranian movie. It’s not a Canadian movie. It’s somehow a confluence of both creating a new space. I feel like there’s real value to creating new spaces and a certain catharsis to that. I actually think our lives are like that! However much we might like to divide the world into binaries, I don’t think our lived experience is like that. I’ve spent time in Iran, but I overwhelmingly encounter that space through Pirouz. He’s spent time in Winnipeg, but he overwhelmingly encounters that space through me. Are we not, in some way, part of the same story? The movie explores that space not as an absolute but as a possibility.

The Tim Hortons in Farsi embodies that possibility. This can be theirs too.

That’s right, it’s about a shared space. How do we create new centers and spaces of overlap? There’s a certain catharsis to building that. Definitely for us, making the film was an enormous catharsis. Everybody learned something. Everybody’s experience with the world was enlarged just by making this thing together, and it belongs to everyone who made it.

People across the world may experience this as a film from Canada, but it’s so deeply tied to a smaller subset of identity. What do you make of having something from such a specific region standing in for the nation at large?

Universal Language, we shouldn’t neglect, is also a very Quebecois film. It references three cinematic languages, but I really gave myself the permission to go into very deep specificity as much as possible. As much as the film is reach[ing] out into the macro of the cosmos, it comes from this very tiny, provincial space. It’s trying to connect those two.

I like to think that the more specific something is, the more universal it is.

I think that’s the pleasure of watching a movie: seeing a world that’s very precisely defined and looking into it. I know so much about Brooklyn based on movies! Growing up, any movie that took place in New York always had a joke about New Jersey, which would go over my head. But then, I was living in New York for a little while, and I went to see some New York films. The Jersey joke would get a huge reaction—like shooting fish in a barrel. People show up for that joke, and they’re ready to laugh. Growing up, I understood that New Jersey must be an object of derision for New Yorkers. I don’t necessarily participate in that, but there’s a pleasure in watching a world that’s precisely defined.

It’s a fine line, and at a certain point, too much is too much. But I know there are little things in [Universal Language] that Iranians will have the fullest pleasure of this specific moment, or French speakers will have the fullest pleasure of that moment, but nothing hinges on that.

I’m hoping you can clear up some confusion I had: Were you literally a student of fellow Winnipegger Guy Maddin’s?

A disciple, maybe. The two Johnson brothers [Evan and Galen], with whom he now directs, were his students because he taught at the University of Manitoba. But I was never his student. I took a workshop that he gave a long time ago, but not other than that. I’m not [a student] in any active way, but I did learn from that. The Guy Maddin model of working on an epic scale with a Dollar Store budget—those were important lessons for me.

Maybe the comparisons feel particularly loud this year because you both have films touring the festival circuit simultaneously, but a lot of people put your work in conversation with that of Maddin. Obviously, that’s a great legacy to inherit, but where do you see the points of convergence and divergence between you?

I love Maddin, and I’m honored to be compared [to him]. It’s true that sometimes when we have to talk about a movie, we compare it to this or that, and that can stick. A lot of people see Wes Anderson in this movie, which was surprising to me, [as] he wasn’t in any way part of my consciousness. Tati definitely was, and, of course, there’s no Wes Anderson without Tati.

They’re branches on the same tree, and I think people are so starved for visually interesting comedy on a grand scale that Wes Anderson might be their only contemporary frame of reference.

It’s a measure of how he’s at the forefront of cultural consciousness, [and] in a way that I didn’t realize. Sometimes, I find myself surprised by how much people insist on comparing a movie to another movie, but that’s how we talk about stuff. It’s a way in, and that’s great.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.