It’s only February, but 2025 is already shaping up as a breakthrough year for Christopher Abbott. His physically transformational turn in Leigh Whannell’s Wolf Man marked the actor’s first time leading a studio film. Just as he contorted his body with prosthetics for Blumhouse’s modern monster update, Abbott ties himself into psychological knots within writer-director Christopher Andrews’s Bring Them Down.

Hearing Abbott sporting an Irish accent and speaking Gaelic may come as a shock to longtime fans of the actor. He was thrust into the public eye in the 2010s through New York’s independent filmmaking community, both on television with Lena Dunham’s Girls and on the big screen through scrappy independent work with the Borderline Films collective. Abbott’s simmering intensity, grounded in his naturalistic and instinctive acting style, routinely makes for the best part of whatever project he tackles. Whether dominating the screen with leading turns in James White and On the Count of Three or contributing to large ensembles like First Man and Poor Things, Abbott always leaves an impression.

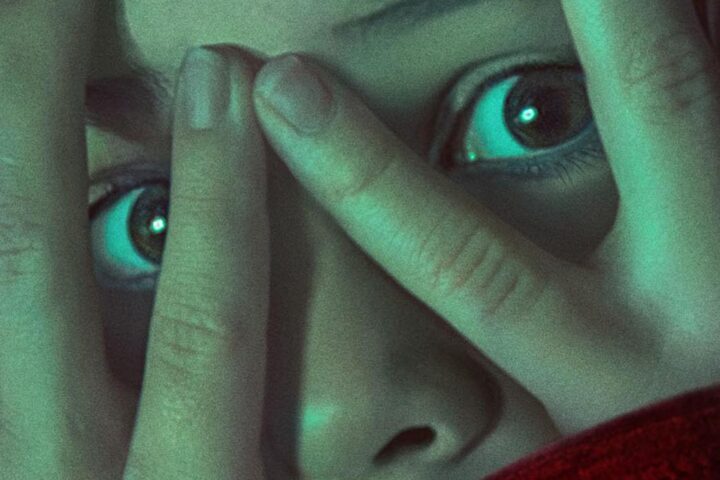

But the brash, brooding essence of Abbott’s typical tortured men remains intact even as he transfers it into the taciturn character of Michael, the last son in a long line of farmers in rural Ireland. The actor’s face is left to express everything ranging from a lifetime of regret toward one-time girlfriend Caroline (Nora-Jane Noone), a momentary burst of anger toward his ruffian neighbor Jack (Barry Keoghan), and the weight of a family legacy dating back centuries with his cranky father, Ray (Colm Meaney). Bring Them Down tells its tale of escalating tensions first from Michael’s vantage point before then doubling back to show it from Jack’s perspective. No matter if he’s the subject or object of the frame, Abbott holds it magnetically.

I caught up with Abbott over Zoom from New Zealand, where he’s hard at work on the upcoming East of Eden miniseries, co-starring Florence Pugh and Mike Faist. Our conversation covered the merging of character and self, where research and preparation are helpful, as well as how Bring Them Down fits into the overall arc of his career.

You did this film before performing in the off-Broadway show Danny in the Deep Blue Sea, which you described as a “swan song” of your angry young man phase. Do you feel a change looking back at this role?

I don’t think I’m in the “young man” territory anymore. Maybe it’s just an “angry man” phase at this point! You can group this one into that territory, but there were a lot of things that felt different and unique about it. Not just the Irish language and accent; obviously, that’s new territory [for me]. Maybe there’s a bigger-picture theme going on that I’m not aware of. I’m just doing angry young men in different accents constantly. [laughs]

What does learning a new language do to help you unlock the character? I chatted with your frequent co-star, Alessandro Nivola, and he told me how the vocal nature of a character is a great entry point into how they present themselves.

I love Alessandro, man. Yeah, it reveals a lot. What I like about it is that it forces your hand a little bit and does a lot of “character work” for you. I’m speaking a different language; that’s character work inherently. I don’t even have to think about it too much. I just have to commit to it. It’s a very cool, unique exercise. I’ve only done it a couple of times to speak another language, but I like the practice of working hard on the language to then feel free. That process is interesting because, at first, you feel restricted by it. Then, you break it down so that you feel free. And feeling free in another language on screen is an inherently very freeing thing to do.

How much of a character like Michael has to be built from scratch? Are you able to draw on previous roles of self-destructive guys?

I would say it’s mostly on the page. I don’t quite have a specific process, but the constant thing throughout is to prepare, prepare, prepare, and then eventually let it all go. That’s just the basic thing. When I first read something, I don’t even necessarily think of the character as me. I almost have an image of someone else in my head, you know. You start there, but then the idea is to bring it back to you. I’m working now, so I’m doing this now. How do you like flesh that out completely to then be able to trust that it is me, my face, and my voice? Maybe through an accent, but that’s the interesting process that I like.

How much of it can you intellectualize, and how much of it has to come from the concrete details of being out on the land or with the sheep?

That’s the challenge. My job is to tell the story and commit to the truth of a scene. I try to be as open as possible when I get to set. It’s an interesting process because it just changes on a daily basis. I have days where I feel good, and I have days where I don’t. On the days where it feels good, I think it’s just [about trusting] in the preparation and [knowledge] that you’re telling the truth at the same time. Playing a character but then using your own experience at the same time…however that mixes. It’s tricky sometimes, but when it works, it works well.

How do you power through the bad days?

That’s an exercise in letting go. I can’t think about the end product too much while doing the thing. That’s the daily struggle of shooting something. Sometimes, you only get one shot and one day to do a scene. But that’s the beautiful thing about it. Sometimes, it’s imperfect, but it’s what it was that day, and that’s all you have. But then you go down a rabbit hole, and you’re screwed. Because if I’d shot a scene on a different day, where I was maybe feeling not as tired or all these other human daily factors [weren’t] involved, maybe the scene would have been different. That could have been for better or for worse. Whatever’s out of your control is out of your control.

How does the audience’s perspective affect both how you act and how you’re perceived? It struck me during the back half of the film that I might feel differently about Michael if I saw Jack’s side of the story first.

Not to keep relieving myself of duty here, but my job is just to tell the story as best as Chris wants me to and play the truth. But I have a filmmaker’s mind in the sense that I’m aware of how this thing is going to be edited. I’m not saying I’m just going in like a hippie every day and just being like, “Whatever happens, happens.” I’m aware of how it needs to cut together and how this scene leads to this. It’s a very amorphous thing. It’s not a ball that you have control over. It’s like a glob just constantly falling through your fingers and [trying to] catch it.

Did the task of playing Michael change at all in each half of the film? If you knew it was your perspective rather than someone observing you, does that affect the way you approach playing a scene?

The short answer is no. I didn’t think about it like that. But it’s a good question because it’s something to think about in anything if the camera and the audience are the perspective of whatever character. Obviously, I don’t mean just POV where you’re looking at what I’m looking at. Maybe you do sometimes have to change how you play it based on the audience’s perspective in that moment. I didn’t think about that, but now I will.

You just mentioned that so much of the work of finding the character is done for you on the page. Especially with this character who expresses a lot but little of it outwardly or verbally, how do you find him between the lines?

I love that stuff. Someone asked me earlier about a scene that [people] may not think is a favorite, but honestly, one of my favorite shots that I was happy Chris left in was when I’m just taking a break and eating a sandwich with the dog sitting there. It can be boring, and it’s not particularly emotional. It’s just a very observant moment in this guy’s day-to-day life. I love that because so many scripts, not to a fault, are all about the story. I love it when there are moments that aren’t about the ABCD of plot points. I like the in-between. I prefer the in-between!

I’m glad you brought up how he eats on screen because I had planned to ask about the very specific way he puts jam on the toast in an early scene. How are you thinking through all of these different ways he would do certain tasks?

It’s not like I planned it like, “I’m gonna do this,” but I think something happens when you’re just there. For that specifically, it’s such a boring fucking thing that he’s eating. It’s so lame. Maybe the only thought behind it is that this is just sustenance. There’s nothing romantic about it. I think that’s the only thought I had.

How much of building the character comes from learning the Irish context, and how much is it just playing him as a guy who just happens to be in Ireland?

I think it’s a bit of both, really. To go back to the process of [bringing the] character into being me and present, it falls somewhere between that. I can do all the research I want about that area in Ireland and the history of the Irish sheep farming families that goes back hundreds and hundreds of years. But there’s only so much you can play. I can’t play 500 years of family sheep farming communities. I can only play the scene. It’s really a mixture.

Is it helpful to think through the allegorical or biblical resonance that Chris has built into the script, or is your job purely tied to Michael’s immediate reality?

Exactly. As an audience of this film, I love those allegorical themes. I think it’s so cool. It’s a small story set in a rural, small kitchen sink setting, but it has these much bigger picture, good-shepherd parable things that are happening. That’s me as an audience, but then playing it, you just have to play the truth of it and commit. Commit to eating a sandwich next to a tree as much as I commit to carrying a head around. It’s truth, no matter what, ideally.

One thing I noticed a lot researching for this is your frequently expressed admiration for Tennessee Williams. Does the Irish context give you some new insight into the more American brand of masculinity that defines Williams’ work?

I think you can switch out accents for anything. Those themes are universal, no matter where you’re from. You can make the argument for, geographically, what it means to be in a rural setting versus a very urban setting. Does this story work in New York City? Probably not just because of the environment. The story is so connected to the land and the animals. You can place that anywhere in America or Canada, that’s the thing.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.