It’s often said that those who forget the past are doomed to repeat it. Based on the breathtaking creativity of the games we’ve played so far this year, we acknowledge game developers as the historians they are, because every title on this list represents a moment where the past has been celebrated as a foundation upon which something new has been built.

Indeed, a sense of history informs the culmination of a storyline 10 years in the making, as well as the beginning of a new saga informed by the sense and muscle memory of a past platforming classic. History, too, is at the heart of the many ways in which one remake purposefully set out to pick and choose which aspects of the original to deepen. Above all, without history there would be no nostalgia, and it’s been a pleasure to watch studios bait that hook with deck-builders or strategy games that seem familiar but are instead their own brave, bold new things.

From the pointed drudgery of a sorting game that preaches rebellion against a heartless corporate machine, to the filmic metaphors of a living maze of memories, to a board game-esque conquest of hell, good luck forgetting these titles. Just as many were inspired by games made decades ago, each is likely to inspire those we speak about in the future. Aaron Riccio

1000xResist (sunset visitor 斜陽過客)

At the heart of 1000xResist is a nightmare experienced by a teenage girl, Iris, traumatized by her experiences during Hong Kong’s very real and recent political turmoil. That trauma ripples throughout generations—of clones of Iris governed by an unfeeling Allmother, to be precise—but the scope of sunset visitor 斜陽過客’s vision of an unknowable future turns that trauma into everyone’s problem, in this world and beyond. More than that, the game argues that it deserves to be, just as space needs to be not just given, but demanded for people to reckon with it in their own way. But it’s a messy process, and made messier by the ugly confluence of technology, religion, and psychology, not to mention the memory-eating alien threat that’s already decimated the Earth. 1000xResist is an unexpected bullet to the temple, an exploration of societal pain dressed up by wonderfully dense dialogue, expansive sci-fi writing, and an unfathomably deep pool of ideological reference points. Justin Clark

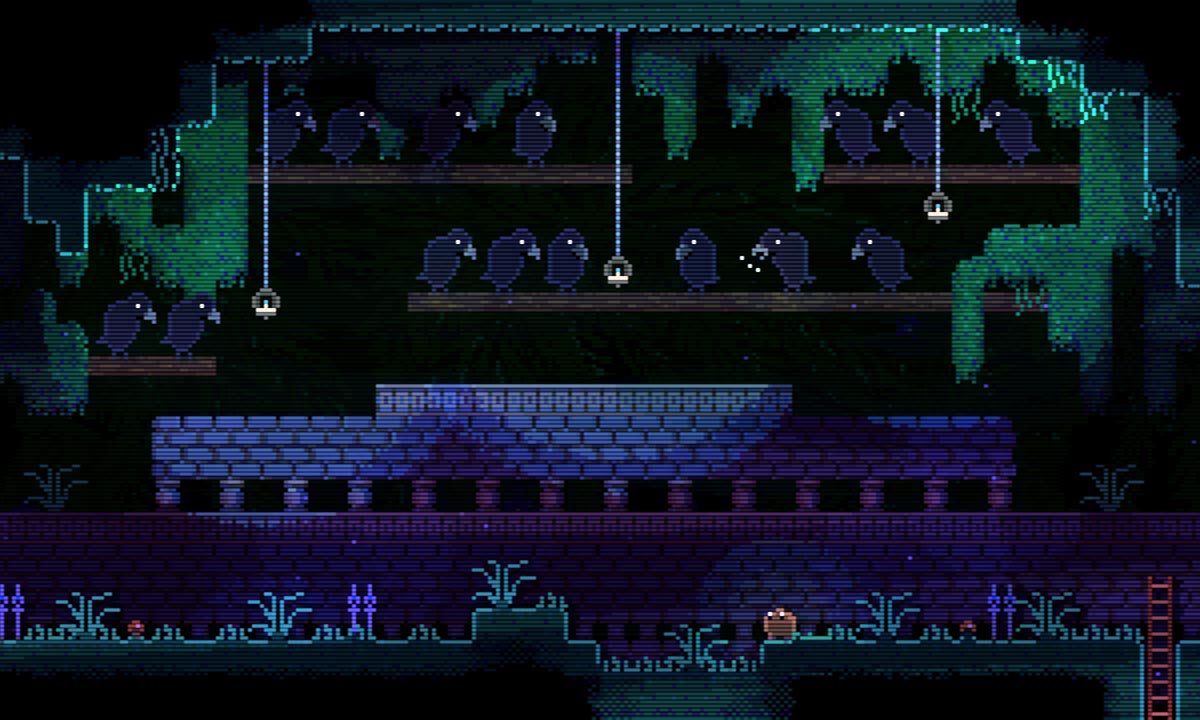

Animal Well (Billy Basso)

There’s a bit of popular wisdom about games made using a retro aesthetic that says they ought to look, sound, and play like your nostalgic memory of them, rather than being actual recreations. Animal Well, from developer Billy Basso, looks, sounds, and plays in a way that, had it existed 30 years ago, might have made you think your cartridge was haunted. Despite its litany of tricks, the game is relatively simple at its core, with little in the way of an overarching mystery or narrative to push you along. And while the lack of long-term hooks sometimes makes the game feel a bit slight, the single-minded attention to the in-the-moment pleasure of the gameplay creates a focus that is meditative rather than expansive. Animal Well isn’t some grand adventure or sweeping artistic statement. It’s just a boatload of tiny interconnected puzzles, woven together to form an almost unimaginably intricate web. Mitchell Demorest

Balatro (LocalThunk)

Maybe it’s the fact that developer LocalThunk had reportedly never played a deck-builder before that makes Balatro so much more exciting than most of the competition. Where plenty of games offer up riffs on the formula pioneered by Dream Quest and popularized (and honed) by Slay the Spire, Balatro feels sui generis. In most roguelike deck-builders, the wide selection of cards and buffs you can win or purchase makes each run a process of perfecting the racing line on your way to an idealized deck. Here, the relatively small slice of the game’s huge array of game-changing Jokers on sale at any given shop forces you to improvise in wildly unpredictable ways, often pushing you so far as to change plans drastically midstream—less Olympic slalom and more drunken cross-country. And the recklessness of its scaling—demanding exponentially higher scores as you progress into the aptly named Endless Mode—gives the sensation of trying desperately to outrun an avalanche that will inevitably swallow you whole. Demorest

Botany Manor (Balloon Studios)

At a glance, the 1890-set Botany Manor looks like any number of puzzle games inspired by The Witness, but Balloon Studios’s debut has something else on its mind. Botanist Arabella Green is working to complete her research book, Forgotten Flora, an herbarium covering the unusual plants she’s cultivated in the titular manor. Playing as Arabella, growing and cataloguing each plant is its own unique puzzle, some requiring different temperatures, environments, even sounds to grow and flourish. Despite her talents, though, Arabella’s work is overlooked and downplayed by the casually sexist academics of the era, and the game documents her struggles and relationships as she overcomes ugly, dismissive attitudes. Gorgeously rendered with bright, imaginative visuals, and enhanced by a beautiful score that lingers long after the game is complete, Botany Manor piercingly contrasts the tyrannical and exclusionary patriarchy with the liberating nature of Arabella’s enthusiasm and creativity. Ryan Aston

Children of the Sun (René Rother)

The nameless, masked protagonist of Children of the Sun has only one bullet per level, but she uses it so deftly, telekinetically guiding it through the air, that it’s all she or the game needs. That’s not to say that this is a thoughtless game. You can’t just point and shoot, and the first half of every level is spent circling your targets, trying to pick out and tag the yellow-clad cultists among the darkly hued environments, as if you’re playing the world’s most morbid version of Where’s Waldo? Once that’s done, you have to figure out how to make a bloody daisy chain of victims as you redirect the bullet from corpse to corpse, later gaining the abilities to slow down and bend the bullet, Wanted-style, around corners, to accelerate fast enough to puncture armor, or to propel the bullet (as if you’re re-firing it) in a new direction. It’s only fitting, then, that each level ends with a top-down map of your physics-defying trajectory, underlining the fact that the ability to take out 14 different targets at once very much puts the art in arterial spray. Riccio

CorpoNation: The Sorting Process (Canteen)

The first few hours of CorpoNation: The Sorting Process aren’t exactly a blast, but that’s by design. As complexity is added to your job with little warning and often unclear instructions, you realize that the game is about more than just the severity of the discomfort imposed on you. The kind of half-engaged mental autopilot that the game has you reflexively slipping into during your sorting shifts will likely feel disquietingly familiar to anyone who’s worked a similarly repetitive and menial job. As the game slowly introduces new elements into your daily routine, the uncomfortable similarities to the real world continue to pile up. For instance, the main state-approved game, Ultimate Ringo Fighters, that you have access to in your living pod functions as a rather scathing satire of modern live-service games, as this online fighting game boasts microtransactions, seasonal rewards, and a rather awful matchmaking mechanic. Demorest

Crow Country (SFB Games)

To call Crow Country pleasant would seem to clash with its horror setting, an abandoned amusement park whose ransacked corridors are now home to a horde of rotting mutants. But the game nonetheless exudes a rather cozy atmosphere, with its lo-fi style bathing this house of horrors in a warm glow of nostalgia. The colors pop beneath a hazy PS1-esque filter, and the textures are smooth and shiny, reminiscent of early 3D’s plasticene aesthetics. The through line for Crow Country’s puzzles is observation, which plays to the game’s strengths. The simplicity of its lo-fi style aids the act of exploration, ensuring that nothing is buried by the visual noise of quote-unquote “realism.” The park’s backstory can be a bit sparse, but Crow Country’s attention to detail brings the place to life, down to small touches like how the decorative crow-headed trash cans are only used for the public-facing areas. Steven Scaife

Destiny 2: The Final Shape (Bungie)

The Final Shape’s campaign is an intimate reckoning for all of the Tower’s major figures for the sins portrayed in Destiny expansions past, their failures amplified and perverted to the point of near-insanity by the Witness. Even without the late Lance Reddick bringing Vanguard leader Zavala’s story to its conclusion (Keith David admirably takes up the mantle), these stories pay off every ounce of the player’s work from the last few years. And the narrative and mechanical successes ensure that the big blowout climax hits as effectively as it does. Accessing the final mission was a community effort, and it’s wonderful for the way it makes high-level players feel just as much a part of the universe as its lowest level scrubs. But beyond being the final beat of a decade-long story, that mission is a bombastic technical marvel. It’s a victory lap, and Bungie knows it. More importantly, over the course of 10 long years, Bungie has earned it. Clark

Dragon’s Dogma 2 (Capcom)

Dragon’s Dogma’s creative breakthrough—as a series, since much of what the sequel does was introduced in the 2012 original—is that it conceives of the RPG adventure not as a string of combat encounters or dialogue decisions, but as often arduous traveling through dangerous, unpredictable lands—with all the planning, consequences, and improvisation that entails. This angle is so daring and unusual that Dragon’s Dogma 2, which once again sees you set out as the chosen Arisen on a quest to slay the mighty Dragon (or at least it seems that simple at first), somehow feels unlike anything else that’s been released since the first game. The actual combat that punctuates your winding journeys just ups the unpredictability further. Where Dark Souls and its descendants are all sharpness and patience, and Monster Hunter is all depth and studious fluency, Dragon’s Dogma 2 is barely contained chaos and frantic reaction. Demorest

Elden Ring: Shadow of the Erdtree (FromSoftware)

Elden Ring: Shadow of the Erdtree is more about adding a bit of spice to a perfect recipe than a different main course, though the portions will sure have players fooled, as they tack another few dozen hours onto Elden Ring’s already enormous playtime. The Realm of Shadow is massive, and while not as far-reaching as the Lands Between, it’s more dense, intricate, and vertical, with jagged, imposing mountains to scale, cave systems to explore, and a slew of tiny dungeons of varying length, and it will all require you to take multiple leaps of faith. The Realm of Shadow also isn’t lacking for impressive, unique biomes, though (perhaps thankfully) nothing here is as primally terrifying as Caelid in the base game. Then again, there’s also a village where people are begging to be butchered and liquified into sentient jars. As always, the terror of a FromSoftware game is always there if you look close enough. Clark

Final Fantasy VII Rebirth (Square Enix)

Final Fantasy VII Rebirth’s greatness lies in its granular concreteness. Even in sand-blasted deserts of poverty like North Corel, on the western continent of the planet, it feels like there’s a story explaining why every square foot of the world is the way it is, some piece of history to learn, some weird quirky minigame to play, a flashback waiting to be unearthed, some local resource to be found that only grows in what only seems like the middle of nowhere. More than this, Rebirth puts a premium on learning how and why the world functions the way it does instead of trying to bend the world to your will. Progress requires talking to locals, scavenging ruins to find out what kind of vehicle or chocobo will get our heroes where they need to go. Throughout, the game’s deep-seated respect for the natural world is refreshingly at odds with the “do what thou wilt” approach of most modern open-world games. Clark

Like a Dragon: Infinite Wealth (Ryu Ga Gotoku Studio)

In Like a Dragon: Infinite Wealth, the expected ooh’s and ahh’s about how pretty Hawaii can be give way to a surprisingly straight-faced look at how the effects of colonization, tourism, inflation, and xenophobia simmer on. And not only is the game the first to directly address the Covid-19 pandemic, it’s one of the few pieces of media to give a nuanced look at Hawaii’s unique political landscape, with a plot that ultimately indicts every foreigner—especially the organized criminals—to sully native lands. That makes for a game with a markedly different feel than anything else in the series. All of that is somehow able to break through even when Like a Dragon is back on its usual hilarious bullshit, where Kasuga is smacking around street thugs with giant Hitachi Magic Wands, delivering poke and pizza in a wild Tony Hawk/Crazy Taxi hybrid mini-game, and his new best friend is a cabbie who scrubs enemies to death. Clark

Lorelei and the Laser Eyes (Simogo)

Of the many different puzzle types in Lorelei and the Laser Eyes, the central one is a maze, and the way in which you interact with it speaks to the game’s all-encompassing brilliance. It’s a credit to the Simogo team’s incredibly sharp writing that however obtuse the game’s puzzles may seem at times, they never feel unsolvable. As noted in one of the many bits of sumptuous flavor text scattered about the Hotel Letztes Jahr: “Getting stuck is one of the key parts of the process.” And in holding true to the manifestos of the artists at the heart of the story, Lorelei and the Laser Eyes manifests puzzles as art, requiring the proper interpretations of mixed-media sculptures, paintings, and more. It’s all one unexpected thrill after another as you go deeper and deeper into a maze of memories, metaphors, and magic. Riccio

Minishoot’ Adventures (SoulGame Studio)

In the taut and delightful Minishoot’ Adventures, you guide a sentient, earthbound spaceship on a quest to rescue their friends from a once-dormant evil. The vibrant landscape you scour from a top-down view recalls The Legend of Zelda’s 2D heyday in its encouragement of curiosity. Secret passageways betray themselves with passing glimpses, luring you toward hidden treasures and playful changes of pace, like racing challenges that send you whirling along snaking tracks. Action unfolds in twin-stick-shooter fashion, though a welcome auto-fire setting turns combat into a Vampire Survivors-esque blend of the relaxed and the riveting. As you find and free your fellow ship-beings, they gather in a cozy town, where they provide services while communicating with R2D2-like beeps and endearing full-body wiggles. One character whistles melodies when you interact with them, causing musical notes to materialize and glide into the air, embodying the game’s breezy, refreshing charm. Niv M. Sultan

Mullet Madjack (HAMMER95)

The first few minutes of Mullet Madjack are a flashback to the days when the anime that stabbed its way Westward was edgy, gory, and very much adults-only. For a brief time, anime was a well-kept dirty secret hidden away at one or two in the morning in the dark corners of TV. More than just an aesthetic choice, though, the cel-shaded look of the game embodies that hyperkinetic ’80s swagger of wild-haired heroes exploding heads however they can through gritted teeth and the screaming, bloodthirsty banshees who love them, and as both of them take on an unending legion of squishy cannon fodder. Building actual gameplay around that feeling without it getting stale is trickier, but mechanically designing a game like the watercolor, ADD-riddled hate-child of Bulletstorm and Hotline Miami is a hell of a foundation to start on. Clark

Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown (Capcom)

Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown convinces players to see both traversal and combat as two halves of a whole, with impressive, multi-phase bosses that throw many attacks at you to acrobatically dodge and precisely parry. The fluidity of combat informs the platforming and vice versa, all while gentle checkpointing allows players to remain engaged in mastering harder segments. It helps, too, that Mount Qaf is a cleverly designed place to get lost in. It’s fascinating to see all the ways in which time flows (or doesn’t) throughout the game’s varied regions. These places not only serve narrative purposes, but also thematic ones, in that the astral clockwork calendars of the Upper City demonstrate the terrifying effects of broken time as much as the encounters that Sargon may have with alternate versions of himself. Put simply, time isn’t merely an effect in The Lost Crown—it’s the consequential core of the game. Riccio

Solium Infernum (League of Geeks)

This Solium Infernum resembles an elaborate board game due to its measured pace and the tactile quality of your demonic holdings. Its masterstroke is how much commitment it requires, to the point that the simple act of moving a unit, the bread and butter of most strategy games, carries a weight on par with all manner of subterfuge that might better suit your purposes in the long term. Also, the game is played over such a long period of time and involves enough random elements that you can’t possibly form a foolproof plan, and such entrancing chaos is what makes Solium Infernum shine as a multiplayer experience. More so than the original, it feels as if this remake, given its specific brand of prolonged negotiations and conniving, will live and die by whether it grows that dedicated audience. Perhaps the greatest compliment I can pay the game is that I very much hope it finds one so I can play more of it. Scaife

Tales of Kenzera: Zau (Surgent Studios)

The look and feel of Tales of Kenzera isn’t nearly as impressive or enduring as its narrative, taking our hero through a whirlwind hellride through the stages of grief. Death himself is Zau’s constant companion in his journey, focusing him on the journey at hand, ever disappointed in his need to prioritize one man’s life against the natural order. Zau’s adventure is, inherently, a fool’s errand but a necessary one for the shaman Zau must become. Zau—and the player—may be playing this game to win, but Death is along for the ride to teach a valuable lesson. With every swamp, every desert, every erupting volcano, Zau is forced to process his grief, to assess the motivations for wanting to bring his father back, and figure out the man he must embody to truly win. And the narrative allows Zau to fail, to be petulant and mournful and pissed off in ways that Black men aren’t always allowed to be in reality, let alone games. Clark

Unicorn Overlord (Vanillaware)

It’s rare to find a game as overwhelming in its technical mastery as Unicorn Overlord. A triumph of granular precision, this tactical RPG plays out like a duel between Rube Goldberg machines—to either satisfying or frustrating effect. But that’s countered by a necessary injection of tactical uncertainty. And the icing on the cake may be the top-notch graphical style. The overworld evokes the ’90s stylings of its inspirations but is richer and more detailed than RPG overworlds of the time. The story might initially come off as a letdown, with its pedestrian fantasy setting and mostly ordinary character arcs, but sometimes stories in games simply serve as a kind of backdrop against which you experience the main event—the play itself. Unicorn Overlord’s predictable plot beats hang out in the background, unoppressive, so that you’re free to let the rush of its expertly crafted systems wash over you unimpeded. Demorest

Ultros (Hadoque)

Every inch of Ultros attests to its themes of ecological preservation. The title is illustrated in a way that reflects the game’s cyclical growth patterns, each letter mutating a bit more than the previous one; the in-game font looks like a clustering, wriggling mass of bacterium; and the lurid, psychedelic setting known as The Sarcophagus plausibly depicts the behaviors of a living spaceship. Everything, big and small, within this revitalization of the Metroidvania works to stylishly demonstrate the game’s commitment to giving life to ecosystems. Indeed, possibly the most impressive thing about Ultros is the extent to which it goes out to justify every single choice that it makes. The time-loop mechanism isn’t being utilized because it’s trendy, but rather because it underlines how the time and deliberation that it takes to repair The Sarcophagus is of a piece with the ecological heart and soul of the game. Riccio

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.