“Juvenile Delinquents Turn Heroes,” proclaims a newspaper headline in S.E. Hinton’s 1967 novel The Outsiders, which was famously adapted for the screen in 1983 by Francis Ford Coppola. And the juvenile delinquents on stage at the Bernard J. Jacobs Theatre are doing the same, rescuing a Broadway season overstuffed with undercooked musicals in an unexpectedly persuasive new adaptation of Hinton’s scrappy, moving story.

This show follows close on the heels of two other book-to-movie-to-musical adaptations, The Notebook and Water for Elephants. But The Outsiders far outstrips them both in the sophisticated storytelling of Adam Rapp and Justine Levine’s book, the adventurous staging of director Danya Taymor, and the dramatically specific and potent score from Levine and folk duo Jamestown Revival. Put another way, The Outsiders is, at last, a darn good musical.

Fourteen-year-old Tulsa native Ponyboy Curtis (Brody Grant) is a member of the Greasers, a gang of long-haired rough-housers from the wrong side of the tracks that constantly, and tensely, circles the Socs (short for Socials), their well-off rivals. Orphaned Ponyboy lives with his older brothers, the surly Darrel (Brent Comer) and the happy go-lucky Sodapop (Jason Schmidt in a particularly touching performance), but his family extends beyond their trio to the local community of teen Greasers who’d kill for each other. Ponyboy, though, isn’t looking to kill, as he prefers reading Dickens and staring at sunsets—habits that few of his friends share.

Even if Ponyboy, with his longing for a different life, may be a natural musical theater protagonist, the novel’s construction, veering between Ponyboy’s auto-anthropological introspection and grim depictions of brawls and shootings and fires, doesn’t suggest song right off the bat. The show’s structure hews closely to the novel, sometimes to a fault, namely whenever the stage seems to heighten Hinton’s melodramatic instincts, especially in the relentlessly sad second act. And the dialogue that rings most false often comes directly from the book, as Hinton’s teen banter doesn’t always translate when spoken aloud.

But Rapp, making his musical theater debut (his first Broadway outing was as the playwright of 2019’s gorgeous and taut The Sound Inside), and Levine (the mastermind who assembled the score for Broadway’s jukebox-raiding Moulin Rouge), have a knack for spinning gold in the musical form. Most critically, they know exactly where songs belong: Even if not all the numbers themselves stick the landing, The Outsiders sets up each song shrewdly. Nearly every musical moment feels earned dramatically and serves the show thematically, either advancing character (like Darrel’s bitter “Runs in the Family”) or throttling through plot (as in “Justice for Tulsa,” the thrillingly sculpted act-two opener). The Outsiders vibrates with the sort of purposeful storytelling through song that other Broadway newcomers like The Notebook so sorely lack.

The exposition-heavy opening number and a rowdy gang anthem, “Grease Got a Hold On You,” that lyrically recalls West Side Story’s “Jet Song,” not to mention Grease, make for a slow start. But, at their best, the lyrics, by Levine and Jamestown Revival’s Jonathan Clay and Zach Chance, marry the unpracticed vocabulary of tough youth with gentle internal rhymes that suggest the crackling intelligence beneath the Greaser surface: In “Far Away from Tulsa,” the score’s loveliest song, Ponyboy’s pal Johnny Cade (Sky Lakota-Lynch) sings, “You could read us stories/And outside in the yard/We’d have ourselves a garden/But we wouldn’t work too hard/And ev’ry night we’d stare up at the stars.” And the music, though it occasionally mushes into a folky sameness, more often seems to explode out of the characters deliberately.

There’s always a stylistic match between these aching, restless kids and the aching, restless music they make. Grant is especially heartbreaking and fully convincing in his hope-spattered portrayal of an early adolescence straining against circumstances that force him to grow up far too fast. Though his voice soars on these songs, his diction could be sharper, since many smart lyrics get lost. But isn’t it refreshing to encounter a new musical with fixable problems?

The vigorously athletic ensemble may suggest Newsies with knives, but Taymor’s staging supplements the writing with opportunities for the individual Greasers to develop distinct identities. Joshua Boone’s Dallas, the Greaser ringleader with a robust rap sheet, is a powerfully ambiguous presence, nurturing to the boys in his entourage but nastily lewd toward the girls he encounters. There are similar contradictions at play in Comer’s Darrel, sacrificing everything for his brothers while remaining unable to express any tenderness toward Ponyboy, and Joshua Schmidt’s Sodapop, unfailingly sweet but irreversibly entrenched in gang violence. It’s Ponyboy, most of all, who embodies those tensions: His creative passions and tender imagination have nothing to do with the motiveless menace of the streets, but he was brought up, more or less, to serve in an adolescent war from which he’s never had the chance to unenlist.

Few musicals have more searingly or sympathetically diagnosed and dissected the sort of involuntary performances of masculinity that undergird the Greasers’ actions. It’s not easy for these guys, so trained in their cocksure aggression, to show love for their male best friends or brothers, or even respectful decency toward the girls who assume the worst about their intentions. (As an older, wiser teenager who finds a thoughtful kindred spirit in Ponyboy, Emma Pittman delivers a fierce humanity.) But just like Hinton did in the ’60s, crafting these characters when she was only 16 years old, the creators of this adaptation condemn the Greasers’ violence while remaining seriously—but never preachily—invested in understanding the fury, isolation, and fear that made these lost souls who they are.

That undirected anger spills out into violence that erupts across the stage, most often decked out as a parking lot complete with gravel-covered ground. (The set design by AMP and Tatiana Kahvegian is at its most effective in a runaway scene as a few planks and barrels morph ingeniously into trains and ladders.) Brian MacDevitt’s dramatic lighting design starkly illuminates a gritty battle in the most effective rain scene on Broadway (sorry to The Notebook).

And while Leonard Bernstein and Jerome Robbins musicalized West Side Story’s deadly Rumble and re-physicalized that show’s brutality through dance, The Outsiders takes a different tack. In the musical’s two most harrowingly visceral scenes of violence, the music drops out entirely, and, while the fighting is lightly stylized by Rick and Jeff Kuperman’s choreography, it also feels queasily real. Like the Sharks and the Jets before them, The Outsiders’s Greasers and Socs glamorize and glorify themselves and their aggression, but, when those bloody confrontations detonate, this show demands that the audience see those scenes as they really are, in startling contrast to the safer surreality of the musical theater form.

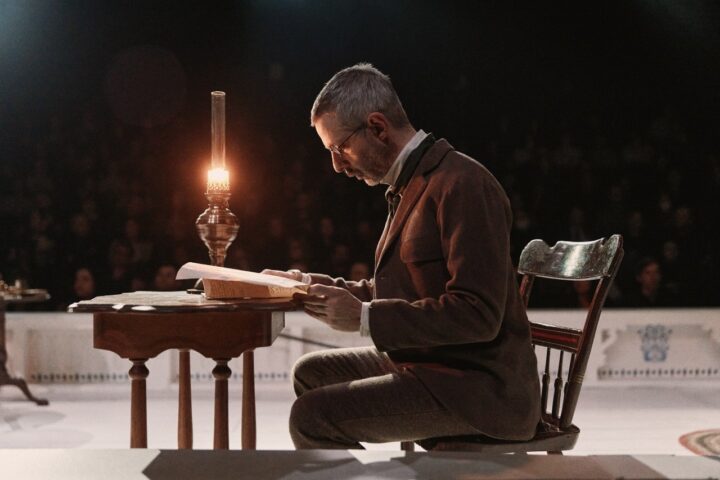

It’s that kind of fully realized theatrical gesture that most distinguishes Taymor’s directorial vision, elevating The Outsiders’s well-made material to a remarkable, emotionally arresting piece of theater. And, in the musical’s final minutes, as Grant’s sorrowfully resilient Ponyboy begins to pen his own self-portrait in the face of unrelenting loss, one could almost call that kind of heart-wrenching theater-making heroic.

The Outsiders is now running at the Jacobs Theatre.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.