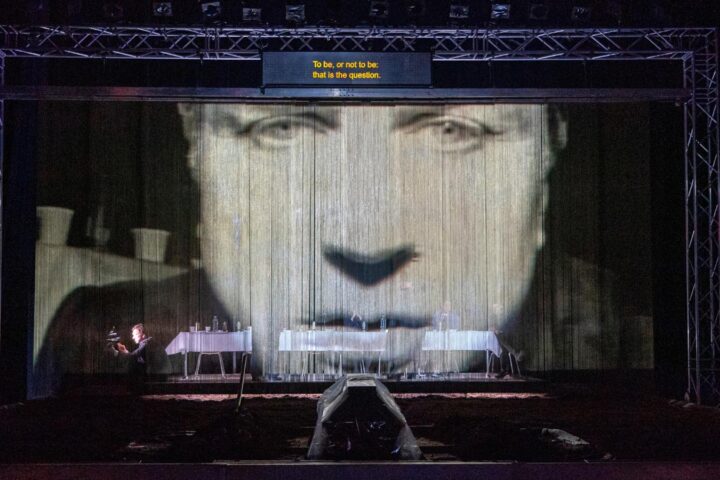

David Hare’s new play, Straight Line Crazy, is generating plenty of buzz for its singular take on Robert Moses, the larger-than-life urban planner and public official who left an indelible mark on New York City, and for the full-throttled performance by Ralph Fiennes, who plays the irresistible monster who wielded power in the city for more than three decades. The production, directed by Nicholas Hytner and Jamie Armitage, has recently transferred from the Bridge Theatre in London to the Shed at Hudson Yards.

Straight Line Crazy focuses on two pivotal moments in the controversial Moses’s career: his battle with the top New York plutocrats of his day over his plan to provide public access to the pristine beaches of Long Island in 1926, and the fight he lost when he tried to ram a highway through Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village in 1955. Throughout, Hare mingles characters of his own invention with real-life ones like Al Smith, the popular four-term New York governor who gave Moses his first break, and Jane Jacobs, the influential author and activist who helped thwart Moses’s ambitions for downtown New York.

Hare’s career has spanned over half a century. The eminent British playwright, also a two-time Oscar nominee (for his screenplays for Stephen Daldry’s The Hours and The Reader) and TV writer, has been regularly produced in New York both on and off-Broadway. A three-time Tony nominee, he’s best known for his incisive and entertaining critiques of the zeitgeist; especially of note are the plays Skylight and Racing Demon and their deft braiding of the political with the personal. Today, the now 75-year-old writer, who received a British knighthood in 1998, is known as one of the most successful English dramatists of his generation.

In 2020, Hare wrote about his near-fatal bout with Covid in Beat the Devil. The raw and witty 50-minute solo piece, which starred Fiennes as the author, channeled what Hare called “survivor’s rage” against the colossal ineptitude of the Boris Johnson administration’s response to the pandemic. Recently, while in New York for early previews for Straight Line Crazy, Hare spoke to me about his particular take on Robert Moses and the kind of theater he favors.

I understand director Nicholas Hytner suggested Robert Moses to you as a subject for a new play. How did you set about approaching him as a subject?

I had read Robert Caro’s book [The Power Broker] 10 years ago and, when I reread it, I realized that a lot of thinking about Moses has moved on since then. It was Caro, as it were, who first told the narrative, but by reading other people and looking at the research, there seemed to me to be another line to take about Moses that would be interesting. He’s one of those archetypal [figures] where you can take any line you want, really. And it varies depending on your experience: from being absolutely loathed and despised in urban communities for the damage that he did, and for the way he ripped through parts of New York, to being admired by others because he was a public builder on a scale that probably America has never had.

Our very own Master Builder?

Indeed. And, in fact, I had done an adaptation of [Henrik Ibsen’s] The Master Builder with Ralph Fiennes at the Old Vic in London [in 2016]. It was one of those great performances and a sort of template for a great architect.

You mix real life people and their actions with invented characters in the play. Can you elaborate on your process with regards to that?

Moses has become a historical character, I think, rather than a real-life character. To me he’s like a fictional character, really. The story of my play is imagined and the characters around him are all imaginary characters. There was no Finnuala and there was no Ariel [Moses’s chief assistants in the play]. The idea of a group of people who worked together for 30 years, I made that up. The story of what happened to Moses in my version—and this is different from other people’s versions—is that he started as a genuine idealist, but the dream that he had was extremely rigid. To realize that dream—a democratic dream to hand over this great beach to the people—he believed that the instrument of liberation would be the car. But opinion changed about the car, surprisingly early. The change of mood happens in the 1950s and then you have Rachel Carson writing about the environment, Kate Millet writing about feminism and Jane Jacobs publishes The Death and Life of Great American Cities in 1961. Suddenly in this century, these three revolutionary writers appear, each attacking a different area of what we would now call patriarchal toxic male dominance. So Moses to me is a tragic figure because he does start as an idealist but then becomes trapped, unable to adapt the dream as time goes by.

Did you draw on your personal experience of visiting New York in the 1960s?

I came over in 1965. I can remember the feeling that Jane talks about, the vitality of the city. And I remember the days when you would stumble into a working-class block and next to it would be a rich people’s block and next to it would be a middle-class block. The feeling that everything was jumbled together gave New York its singular vitality. Jane was obviously inspired by that: people living cheek by jowl from different backgrounds and different communities, different classes and different incomes. New York is diminished, I think, for that not being as true as it used to be. Now when I come here, it’s changed completely. I don’t know any young person who would think of living in Manhattan now.

Who could afford it?

That’s what I mean by being diminished. There was a racial mix that was really quite extraordinary in the 1960s. I’ve never seen anything like that and, of course, it was an inspiring place to be. Now it’s become a [playground] for the rich, which is why I have Jane say that line about whose fault it is. Is it the fault of the conservationists who’ve kept the nice places nice but only for the rich and thereby destroyed the character of those places?

You’ve said in the past that you like to write about people who have a stubborn streak. Is that what drew you to Moses?

I like monsters. I know toxic white males aren’t great to work alongside, but they’re great to write about. And Ralph Fiennes is pretty much a monster in the play.

Did you have Fiennes in mind when you wrote the play?

Not really. It was Nick Hytner’s idea. He just read it and said, “Well, its Ralph isn’t it?” In the last 20 years the actors who I’ve worked with the most are Ralph Fiennes and Bill Nighy. And I seem to work with them more and more. So I’m always happy when it’s either one of them.

You recently wrote the script for Fiennes’s film The White Crow and last year he played your alter ego in Beat the Devil. What draws you to him as an actor?

Ralph is very aware of and loves the classical tradition and he wants to be part of it. So, I adore him for that. And Ralph loves the kind of mainstream play that I write. He’s a very singular example in Britain—Judi Dench, I suppose, is the only other one—who’s as big a film star as they are a traditional theater actor. That is an almost impossible combination now, I suppose. We lost Tony Hopkins to the movies, Gary Oldman and Benedict Cumberbatch. There isn’t anybody that I know but Ralph who will come out of Covid and go ‘round the country to help regional theaters by doing a one-man show of T.S. Elliot’s Four Quartets.

Regarding Beat the Devil, which is currently on Showtime, are there any plans to stage it in the U.S.?

Not that I know of. Nobody has offered. What happened was, I gave a three-minute talk on the radio about having Covid and it got an incredible response. People said, “You’re the first person to describe what it’s like to actually have Covid.” There’s all this talk about Covid but not what it’s like if you have it very badly. I did—in a life-threatening way—so I described that. After that talk, Nick Hytner asked me, “Why don’t we do this in the theater?”

Having come through all that, how do you feel now?

I’m absolutely fine now. Unfortunately, I then got another illness, so I’ve had a long time of being ill and in hospitals. I had two life-threatening illnesses in succession, but it’s over now.

Does that change your outlook in any way?

Very much so. I’ve always wanted to get a certain amount of work done and obviously it becomes more and more urgent when you’re a playwright in your 70s. The culture is slowing down, and it’s much harder to get a film made, to get a television series made, to get a play made. It’s almost as if we’re coming out of a post-Covid dream and everything seems to take forever. It took us three years to get Straight Line Crazy on because we kept having to cancel it, or postpone it rather, because of Covid. That’s very frustrating.

What’s next?

Well, I’ve written another play. That’s really the next thing I’ll do, and we’ll see when it goes on.

You have always had strong views about the kind of theater you like and the kind of plays you want to write. What did you mean when you referred recently to a proliferation “pious theater” that gets produced today?

What I was talking about was plays where you just go in and are told what you already know. In England, at the moment, there are an awful lot of plays which basically celebrate liberal truisms and expect you to rally ‘round and kind of be affirmed in what you believe. But, you know, I don’t need to be affirmed in what I believe. I need to discover new things. So, plays which develop in unexpected ways, that make me feel things I haven’t felt about, or think things I haven’t thought about, they’re the ones I love. There’s a sort of falling back, perhaps as a result of Covid, on to these liberal truism plays. I prefer audiences arguing. One of the lovely things, I think, about Straight Line Crazy is the arguments that I’m getting from Americans—the reaction of “we went out to dinner and we never stopped talking about it.” Not about the play, but about who Moses was and the issues raised. I love reverberation—that’s what I’m after.

Is putting Straight Line Crazy on in New York any different than it was when it was done in London?

We thought that everybody here would know about Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs and therefore it would be different. We thought that people might feel so strongly that Moses is a villain that they don’t want there to be a play about him—that the feeling runs very deep about the things he did and the price that was paid for the imposition of this road structure. But that anger—well, it’s only after a few previews so I can’t really say. Of course, younger people don’t necessarily know about Moses. There’s not the tremor of recognition that we expected for the words “Eleanor Roosevelt,” for instance. Those words mean a lot to my generation. We’re in the 21st century and these people who so shaped the way I think and feel, you know, they’re gone.

Do you think the conversation about urban planning has resonance today?

It doesn’t need me to point out that we’re presenting this play in Hudson Yards. Go figure!

What would you like most for audiences to take away from this play?

Oh, what I’d like most is for people to argue. The young Black architect, Mariah, says at the end that she has heard someone say that what this city needs is one man to come along and impose his will on it. [laughs] I don’t think any city needs that! I really don’t. I think that kind of superman behavior can have horrendous consequences.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.