English actor Ralph Fiennes moved with great ease from performing on the London stage, mostly as a Shakespeare interpreter, to the world of film, winning early acclaim for his performance as a sadistic Nazi prison commandant in Schindler’s List. He was nominated for an Oscar for his performance in Steven Spielberg’s film, and again for his soulful turn in Anthony Minghella’s The English Patient. Fiennes possesses an innate gift for creating intimacy between himself and his co-stars, which he channeled into his first film as a director in 2011, an ambitious adaptation of Shakespeare’s Coriolanus, which he shortly followed up with an adaptation of Claire Tomalin’s 1990 novel The Invisible Woman.

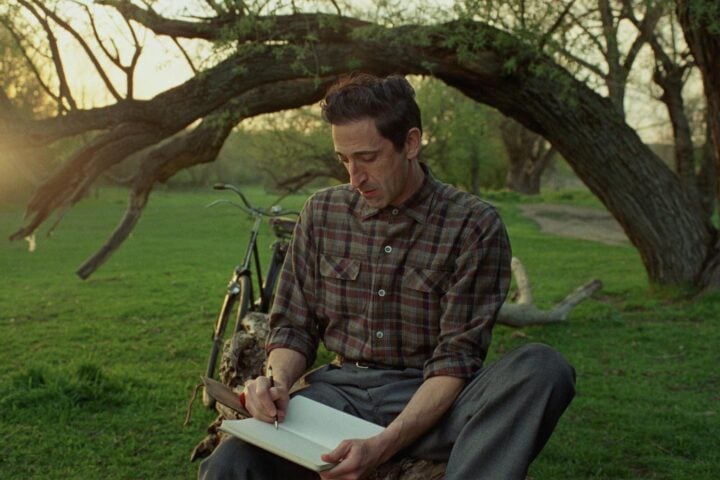

Fiennes’s latest film as a director is The White Crow, the first biopic about Russian ballet superstar Rudolf Nureyev. The title refers to the name the young Nureyev was given in school when he was growing up, identifying him as the odd one out among his fellow classmates. Starring Ukrainian-born dancer Oleg Ivenko as the adult Nureyev (and Fiennes himself as Nureyev’s teacher, Alexander Pushkin), the film, based on Julie Kavanagh’s 2011 biography Rudolf Nureyev: The Life, switches back and forth between the dancer’s childhood in the central Russian city of Ufa, his student days in Leningrad (today St. Petersburg), and Paris, where he made his dramatic defection to the West in 1961.

In a recent conversation, Fiennes discussed the making of The White Crow, his affinity for Russian culture, and exploring Nureyev’s life in nonlinear fashion.

What drew you to tell the story of Rudolf Nureyev’s life on screen?

Julie [Kavanagh] sent me the first five chapters of her book in proof copy—about 1999 I think it was. At the time, I had no conscious desire to direct. I just thought this was an extraordinary story. I didn’t have the other chapters to finish until later when the book was published, but it sat with me. Some years later, I had made two films and producer Gabrielle Tana—she has a background in ballet—asked if I wanted to move forward on this for a film. It was then that we approached David Hare to write it.

Why did you approach Hare specifically?

I know David is very good at writing what I call provocative, high-definition characters. I knew he relishes writing with wit and compassion. Also, his instinct about the world and the social political context in which dramas can happen is very strong. I love his plays, but I think he’s a brilliant screenwriter. He loves film, and he thinks very filmicly. He said he remembered reading the biography and it moved him very much. He completely got pleasure out of the size of Nureyev’s character—his vulnerabilities and then his ego.

I thought of this as the story of the emergent young Nureyev. David was interested in the Paris aspect and I came advocating the Russian background. We both felt that we wanted to explore it in a nonlinear way, with three different time frames interacting, jostling against each other. We wanted this exciting dynamic as you go from one time frame to the next.

I’m curious if you have an affinity for all things Russian?

It’s an affinity and a curiosity, and something of an infatuation, which I recognize is sometimes a bit naïve, because Russia is complicated and not an easy country in so many ways. But I’ve been there over the years, and I actually made a film in Russia in 2013: Two Women, directed by Vera Glagoleva, an adaptation of Turgenev’s A Month in the Country. There’s a connective warmth I feel from the people and a shared interest in Russian culture. I guess life takes you somewhere and you make connections and want to continue keeping them. Sometimes there are things, you know, that politically are disturbing and hard to accept. There are definitely worrying things that go on in the way the state curates its artists. But I have these friendships there and I’ve had experiences that I felt to be very rewarding.

But the Russian ballet stuff was a whole new thing. I came to this story because of the ferocity of who Nureyev needed to be. That was compelling to me, like some Greek story, of a kind of god-man who challenges the gods. I responded to it in some kind of Jungian way, I suppose. And then I had to get to grips with the ballet. And that was scary, out of my comfort zone. I had to do major immersion and surround myself with people advising me on it.

Did you specifically want to cast a dancer in the role of Nureyev?

I wanted it to be authentic and shoot it in the Russian and the French language. So, I wanted a Russian in the lead. And I started to feel very strongly that it should be an unknown person that the audience couldn’t project any baggage onto. I wanted a face that was totally new. I knew if I was going to get a dancer, I wouldn’t have the resources to do face replacement or body doubling. I could see my head spinning, being taken up by these technical challenges. So, I thought if I could get a dancer who could act, that would be great. My producer asked, “Should we not get an actor?” And I said that if I did, the moment they raise their arm or something, the world is going to know. This is Nureyev, so he’s got to have it in his body. And also, the way dancers carry themselves, the whole way they’re formed, is different. So, I thought I just couldn’t make a film about a leading dancer and not have a dancer.

Anyway, we set a big casting sweep through the Russian-speaking ballet world and Oleg was very quickly on the list. He has a real ease about him when he’s in front of the camera. I had to guide him a little bit into my sense of Nureyev’s attitude—his hauteur, and that slightly “fuck you” quality in his demeanor. Oleg is very smiley and lovely and warm, but he got it very quickly. He weirdly had an experienced actor’s confidence. In fact, some experienced actors are full of nerves on their first day of a new film. I know I’ve been full of nerves. With Oleg, maybe it’s because he didn’t know what he had to be afraid of. He didn’t come with an actor’s ambition, asking, “What if I fail, what if don’t succeed,” all the wrong crap that you put in your head. He just said, “I’m very lucky I’m here,” and it gave him a sort of openness and flexibility.

What about you taking on the role of Nureyev’s ballet teacher, Alexander Pushkin?

I wanted to have a Russian actor playing Pushkin, but there was a point where the commercial element came in. It was a Russian producer who said to me, “Ralph, if you’re going to get Russian money in your film, why are you not in it?”

You sound very fluent when you speak Russian in the film.

Well, I had to work very hard to achieve that. I had made a film before in Russian. My Russian is quite limited, actually, but it wasn’t alien to me. I can assimilate a new word relatively quickly because I have a little foothold in the language. But also, now there’s the magic of modern technology. I would run off like 20 of the same vowel sounds with my Russian teacher and the Russian sound editor going, “No, no, no, yes, no, no, yes”—and then they would pick the best one. You can literally stitch it in because the sound technology is so sophisticated. It mattered to me that to Russian ears it was plausible. Even so, I think I’ve got a slight accent.

Do you think Pushkin was aware of his wife’s affair with Nureyev?

Well, no one knows what he thought about it. Julie actually gave me all the tapes of the interviews with the people she met in her research and there’s one person who says it was clear that Pushkin’s wife, Xenia, had a predilection for young male dancers. And Pushkin seemed to accept this. There are people who say that he may himself have been gay. But the two of them had a very strong marriage and very strong bond.

Pushkin’s whole world was the dance. He came from a very humble background and was sort of a self-cultivated man. He was a dancer before he went into teaching in the mid to late 1930s. He was known to be incredibly sensitive and very, very kind. And quiet. He was loved, and he obviously got results. His whole mode of teaching—people say that he would just look and make a comment and allow the dancers to discover and correct their mistakes themselves. There is an interview with the older Nureyev saying that every time Pushkin gave you a combination of steps, it all made sense. Pushkin was very protective of Nureyev. People thought he gave Rudolf too much attention.

Almost like he was in love with him?

I think a bit, yeah.

Is directing movies something you now wish to pursue more than acting?

I know I need a bit of time to find the next thing. What I love about directing is that another part of my brain is being challenged. I love the interaction and the people who are there to help me realize something and, indeed, bring their own talent and artistic ideas to the table. It was thrilling talking with David about creating the piece, and then putting it together with a cinematographer, and then the editor. And then the actors—I just love the process of nurturing a process with an actor. I find it rewarding to see how a character can evolve. I think a lot about Anthony Minghella. Of all the directors I worked with, he was the one who gave a lot of time to actors and was most curious about what actors would reveal. He’s often in my head as a sort of spiritual mentor.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.