Deep in the Australian Outback, Kitty Green is, once again, asking us to sit on a knife’s edge, where the threat of violence is constant. In The Assistant, which also starred Julia Garner as a headstrong underling in an environment dominated by men, Green was attuned to the systemic abuses of the entertainment industry. In The Royal Hotel, she considers the ways infrastructural inequities pervade even in the most remote corners of our world.

Green’s film is loosely based on the 2016 documentary Hotel Coolgardie, in which director Pete Gleeson provided a glimpse into a remote mining town where backpackers are cycled in and out as bartenders, or, as a sandwich board labels them in The Royal Hotel, “fresh meat” to be ogled at and harassed. Here, that fresh meat is Hanna (Garner) and Liv (Jessica Henwick), two American tourists who’ve desperately sought out a work-tourism exchange program when their money abruptly runs dry while partying on a yacht off the coast of Sydney.

The Royal Hotel rarely leaves the titular bar hotel located in a desolate part of the Outbook (the film was shot in Yatina, a town in southern Australia with an estimated population of 32). The exchange program employee (Bree Bain) warns Hanna and Liv to get used to having male attention, which ends up being a cruel understatement, as the Royal Hotel’s male clientele practically froths at the mouth at the sight of them. Even Glenda (Barbara Lowing), almost always the sole female patron in the room, is just as keen to scream sexualized epithets at them.

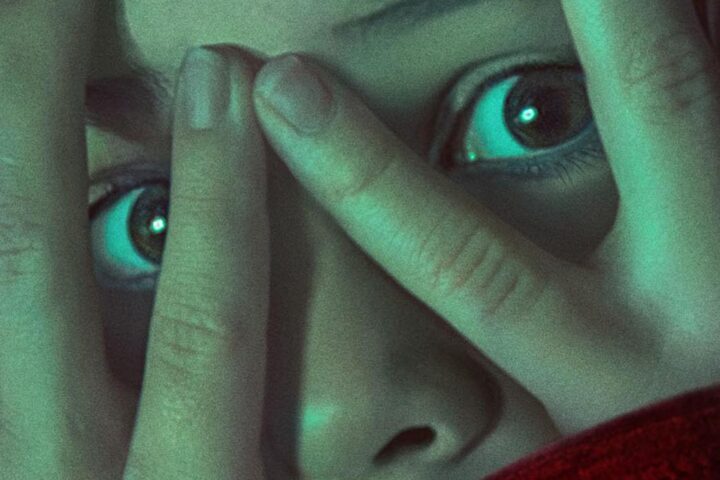

Hanna and Liv are extremely close friends but they each handle the “male attention” with vastly different approaches, which the film subtly suggests is informed by whatever they seem to be running from back home. Liv is more or less content to be flirted with, and is oddly apologetic when the insidious Dolly (Daniel Henshall) acts in such a menacing way that it threatens to turn this thriller about workplace abuse into a real-deal horror film. But while Hanna is more vocal against the behavior that’s been normalized in this place, she’s also the one more susceptible to matters of the heart, falling into a tentative romance with Matty (Toby Wallace), whose cheeky flirtations and offers of adventure-filled excursions are still laced with dread.

The owner of the rotting and sticky hotel is Billy (Hugo Weaving), who calls Hanna a “smart cunt” early in the film. Those sharp-toothed words are emblematic of the film, where nearly every exchange perversely straddles the boundary between positive and negative association, in this case between insult and compliment. The young women try to make the most of their bizarre new existence, embracing the perversity of sunbathing inside a dried-up outdoor pool and even bust a gut when they catch one of the hotel’s outgoing tourist-employees having aggressive sex with a patron in one of the upstairs bedrooms. But soon the torrent of sexual aggressivity is difficult for even Liv to wave away as a matter of “cultural difference” and the two young women find themselves in an increasingly tense fight of sorts for their survival.

Just as in The Assistant, The Royal Hotel’s sonic landscape is used to build a suffocating sense of tension. Besides the perpetually drunk Billy lumbering behind the bar, demonstrating the proper way to slam appliances shut, glasses seem to always be shattering as tables and stools fall to the floor. Throughout, Green intensely keys us to the subjective experience of Hannah and Liv, and by using many of the horror genre’s audiovisual tropes. In this film of clammy anxiety, the potential of male violence is made to feel as scary as the actual article.

The Royal Hotel’s final moments are a bit pat for a film that thrives on the power of fiery suggestion, and Green and Oscar Redding’s screenplay drops the ball when it comes to at least acknowledging the repercussions that Hanna and Liv’s liberation might have on those who aren’t just passing by here, namely Billy’s Aboriginal girlfriend (and the Royal Hotel’s cook), Carol (Ursula Yovich), and anyone like her who’s at the mercy of white men to pay their bills. Unlike The Assistant, then, The Royal Hotel shows its political hand as a feminist rallying cry, but to the very end, the diamond-hard precision with which Green helps us to feel the deadening effect of sexual abuse remains a necessary, if dreadful, marvel to behold.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.