Just about a year ago, New York audiences breathlessly anticipated the arrival of a heartily hyped West End production of an American classic, Rebecca Frecknall’s pseudo-immersive revival of Cabaret. It was, if not a total disappointment, a letdown, as there was nothing particularly revelatory about Frecknall’s ever-rotating vision of Berlin’s pre-war decadence in a staging that aggressively underlined the material’s self-evident grimness.

And here we are again, anxiously receiving another of Frecknall’s London-lauded takes on an American classic into our prestige-starved harbors. This time it’s Tennessee Williams’s psychological kaleidoscope A Streetcar Named Desire, with Irish A-lister Paul Mescal as the brutish Stanley Kowalski. Is this the underwhelming Kit Kat Club all over again?

Well, yes and no. Frecknall’s production is marked by eyebrow-raising staging choices—a near-constant live drumkit, a heavy reverb on the mics, a series of interpretive dance sequences—that don’t do much to illuminate the play, often even threatening to obscure it. But under all the hubbub, Frecknall has also coaxed two tensely ferocious performances into sharp focus: As Blanche DuBois and Stella Kowalski, Patsy Ferran and Anjana Vasan feelingly define this fatally frayed sisterhood as the dual heartbeat of A Streetcar Named Desire.

Schoolteacher Blanche shows up in New Orleans to stay with her sister and brother-in-law for the summer. Blanche, fancying herself something of a Southern belle—she’s fleeing rural Mississippi—immediately expresses her disgust with Stella’s living conditions, first taking issue with the claustrophobic, rundown apartment and then the boorish, unsophisticated Stanley.

Quickly observing that her sister has gained weight, Blanche insists that she herself hasn’t “put on an ounce in years.” She’s preserved herself in the amber of her girlhood, insistent on remaining as coquettish and proud as she was when she suffered, or perhaps precipitated, a terrible loss over a decade earlier. Throughout, Ferran evokes a fish out of water in the truest sense of the metaphor. There’s a frantic flopping about that motors Blanche’s churning banter as she tries to stave off the reality that she doesn’t actually belong—isn’t actually wanted—anywhere anymore. She’s tried on so many personalities, Ferran’s frenetic shifts seem to suggest, that sometimes she can’t even draw on the right one in the right moment; the seductive flirt might emerge, for example, when she needs to play the upright schoolmarm.

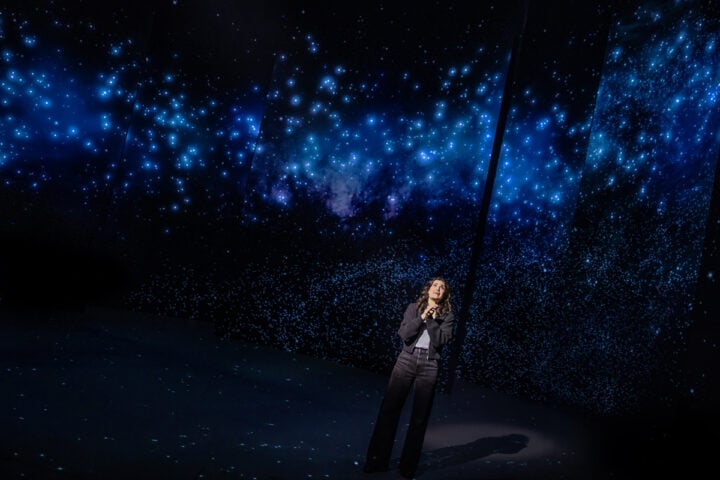

But we’re told that Blanche’s long-dead husband wrote poetry, and she seems to have inherited his tongue for language. Ferran fully integrates all of Williams’s most lyrical passages into Blanche’s frenzy. She’s moving too fast, gasping for air too heavily to hear how beautifully she thinks, but Ferran ensures that we grasp Blanche’s rhapsodic imagination as something more valuable than just a rhetorical web of lies that she’s woven around herself and others.

Vasan, as an increasingly steely mirror, communicates with cool clarity the burden of growing up as Blanche’s sister. Though Stella is gregariously gentle in her initial welcome of Blanche, anxiously evaluating her sister’s wellbeing, those warm embers freeze over as soon as Blanche challenges Stella’s decision to stick with the brutish Stanley.

Vasan and Ferran persuade that there’s a deep, knotty history between the sisters and that Stella’s worked hard to distance herself from Blanche’s shadow. In her iciest remark, Stella offers her needy sister a cutthroat kindness: “I like to wait on you, Blanche. It makes it seem more like home.” In Vasan’s stony delivery, it becomes clear that all the wants expressed and satiated in their Mississippi home were Blanche’s. Stella’s choice to remain with Stanley seems to come from a desire for desire: Stanley represents a freedom to prioritize her own rawest needs, free from Blanche’s demands on her, even if she recognizes that he’s far from perfect.

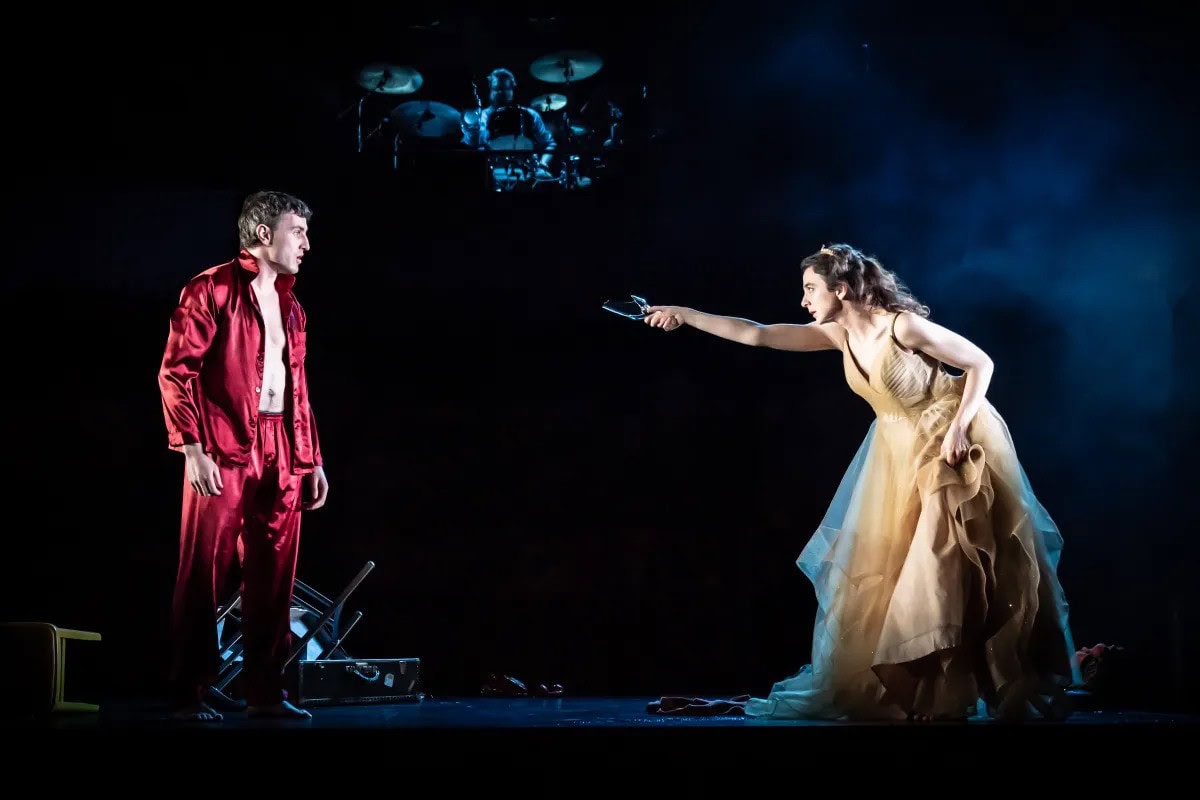

But for all the freshness that Frecknall allows Ferran and Vasan to bring to Blanche and Stella, her over-editorializing of Stanley’s presence leaves little room for Mescal to define the character for himself. During most of Stanley’s scenes, the drums rumble low, eerie echoes invade the audio design, and sometimes a vocalist hums snatches of fractured jazz standards. How could Stella stay so smitten when even the sound designer is telling her to run?

So when this production arrives at the climactic moment when a director should really be able to rip down the curtains and reveal Stanley at his basest self, there’s no surprise or dramatic shift. By telling the audience so explicitly what to think about Stanley in every scene up to that point, it’s clear that Frecknall has had this date with him since the beginning.

Those staging choices leave Mescal, ably assertive and cocky, without much control over his portrayal; even the rhythm of his monologues are dictated by the drums. He becomes, then, less of the third leg of a dramatic triangle than a straightforward bogeyman in a Blanche-centered thriller, menacingly threatening to upend her summer of reinvention by revealing her past.

If Williams was exploring how Blanche and Stanley might mirror each other in their contrasting immoralities, Frecknall has little such curiosity. Decentering Stanley is a fair choice, but it drowns out his specificity with those drums. (Dramatic impact aside, Tom Penn is the impressive drummer who doubles as the doctor in the play’s final scene.)

Not all of Frecknall’s inventions and interventions are distracting. The scenes play out atop a bare raised platform, and the ensemble members playing smaller roles hover outside the perimeter when not in scenes. When a character needs a new prop—for Blanche, it’s usually a bottle—an actor on the outskirts will subtly place it on the edge of the platform, a sleight of hand that sometimes makes it appear as if the set is building itself out of thin air. It’s a lovely gesture, even if this kind of communal storytelling seems out of a place in a play about how easy it is to feel completely, irredeemably alone in a neighborhood, in a marriage, in a family.

Blanche declares, “I like an artist who painters in strong, bold colors, primary colors,” and Frecknall and costume designer Merle Hensel keep the stage awash in the joyous, youthful hues that pervade Blanche’s imagination: bright reds and yellows and blues that seem impossibly bright for the setting. The most coherent reading of Frecknall’s production might be just that: Everything here, from the crashing drums to the sudden bursts of indoor rainfall, represents Blanche’s trauma-addled perspective. But Ferran shows us all that internal tumult already, and neither the actors nor the audience require that kind of interpretive hand-holding.

Crucial to A Streetcar Named Desire’s lasting vitality is Williams’s disinterest in providing psychological answers for his characters’ behaviors. Why do people do what they do? “I don’t know why I screamed,” Blanche admits after shrieking when a splash of Coke spills on her dress. A production that tries to annotate these moments of unknowability, to know more about the characters than the playwright does, may be working too hard at the wrong thing.

A Streetcar Named Desire is now running at BAM.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.