David Henry Hwang’s playfully subversive comedy Yellow Face received an Obie Award and was shortlisted for a Pulitzer Prize when it debuted off-Broadway at the Public Theater in 2007. Now it’s back—in a new Broadway revival directed by Leigh Silverman, the Tony-nominated director of Shaina Taub’s freewheeling musical Suffs. In what Hwang calls an “unreliable memoir,” the playwright—who won the Tony in 1988 for M. Butterfly—places a fictional version of himself, “DHH,” at the center of the story.

The play takes audiences on a clever and humorous journey that blurs fact and fiction. It revisits historical events sparked by the 1990 controversy surrounding the yellow-face casting of a white actor, Jonathan Pryce, in the lead Eurasian role in the mega-musical Miss Saigon. The work also examines allegations made against his father, Henry Y. Hwang, and the increasing prejudice faced by Asian Americans in this country. Portrayed as “HYH” in the play, Hwang’s father, a banker, saw his cherished version of the American dream unravel due to racist-tinged investigations into campaign donations that targeted him in the late 1990s.

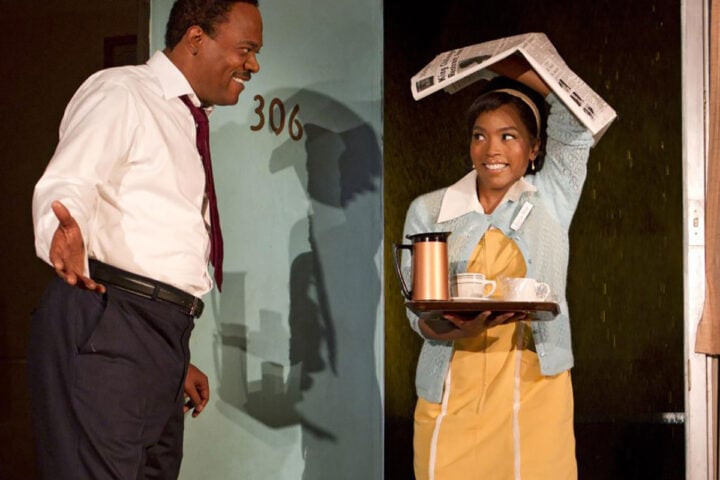

The current Broadway revival of Yellow Face features Daniel Dae Kim (of Lost and Hawaii Five-O fame) as the author’s stand-in and Obie Award-winning actor Francis Jue as Hwang’s father. I recently spoke with the playwright about his autobiographical meta-theatrical creation.

Can you take us back to when you first conceived this play?

You could argue that the origins of this play lie in another play, Face Value, which was my follow-up to M. Butterfly. It was in the early ’90s, and I wrote a comedy of mistaken racial identity attempting to deal with the fracas around the protest against Jonathan Pryce playing the Eurasian pimp in Miss Saigon [on Broadway]. Face Value closed in previews, and was probably one of the biggest flops of the last 30 years on Broadway. I continued to think about that idea for another 15 years or so and then wrote this current play, Yellow Face, also a comedy of mistaken race and identity. But instead of a kind of door-slamming farce, I wrote it as a stage mockumentary which incorporates the history of the flop, Face Value.

How did you decide on farcical comedy to explore the play’s ideas?

I’ve always been interested in comedy. The ability to make an audience laugh, I think, binds us together. It also makes us more receptive to whatever other ideas the play might be trying to convey. Farce is largely driven by situations in which we know more than the characters do—the traditional, you know, the mistress is hiding in the closet. I guess I’ve discovered that you can write a farce in different ways. It doesn’t have to be a door-slamming structure.

Did protests against white actors putting on yellow face first surface because of the casting of Pryce in Miss Saigon in 1990?

I would say that it was the first big national protest against yellow face. And therefore, a lot of the artistic and cultural infrastructure of Broadway, New York, and America rebelled and thought it was an example of political correctness run amok. But I feel I got my start in theater because of a smaller yellow-face protest in 1979, where a white actor had been cast in an Asian role at the Public Theater. The Asian actors of that day, who were few in number and had very little power, protested in front of the theater. Joe Papp [founder of the Public] invited them into his office and ended up hiring one of them onto his staff with a brief to find place for Asian actors. That was how I got into to the Public Theater. So I was really the beneficiary of an affirmative action program essentially, and of an intersection between art and activism.

Terms like “affirmative action,” “political correctness,” and, now, “woke” tend to be used derisively in many quarters today. Has anything changed?

The thing that has changed is that a play like Yellow Face really can come to Broadway now. This is my ninth Broadway show, but aside from Flower Drum Song, which of course was a Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, this is my first show about Asian Americans. Even though there continue to be these debates and controversies and conflicts about whether we call it political correctness or we call it wokeness, that cultural discussion continues.

The Miss Saigon protest wasn’t successful, but it did ensure that such blatant yellow-face casting wouldn’t occur again. Your play juxtaposes respecting racial identity with artistic freedom. Are we going to get to a point where it only matters whether an actor is best suited to a role, regardless of a character’s race?

I think Yellow Face has always tried to hold this tension of competing impulses that, on the one hand, we’re going for a sort of utopian post-racial society, and that, on the other hand, we have to be aware that race still does matter and has consequence. Racist things happen, which need to be addressed. Previously, this show has been cast in a binary fashion—that is, the casts have been white and Asian. In this version, we also have actors of other ethnicities involved. I was wondering if we could effectively have a non-Asian actor of color play Asian roles. It seems to be something that we can accept—and we’ll see how audiences feel about it. That would represent a sort of step forward toward this notion of looking past race.

Can you talk about the autobiographical elements you’ve woven into Yellow Face?

When I first conceived the play, I thought that it would be structured around two incidents that are true—one at the beginning, one at the end. So the one at the beginning was the casting of Jonathan Pryce and the protest, and the one at the end would be the accusations by The New York Times against my father for allegedly laundering money for China. I felt like there was a relationship between these two events, and therefore writing the play was to some extent trying to discern what that relationship is. It just made sense to actually have a DHH character, because I was the link between those two events. Also, to the extent that I wanted to create a sort of stage mockumentary and actually reference real newspaper articles and real-life people who I’ve made into characters, then I needed to at least do the same to myself. Plus, it was useful to have the David character be essentially the butt of most of the jokes, because that way I could create a structure with real-life characters and not offend very many people.

You said somewhere that one has to make a fool of oneself in order to have a conversation about race.

That does sound like something I would have said!

So you had no problem making your alter ego come off the worst in the play.

Right. David makes these huge mistakes in the show. The plot is centered around him trying to cover up those mistakes, but at the end of the show, he’s able to take some accountability and he’s able to move on. I feel that there’s something important in 2024 about saying it’s okay to make a mistake. And if I can create a character based on me who makes the most mistakes, that’s a very clear way of trying to say that.

The play also refers to the anti-Chinese sentiments faced by Asian Americans—the allegations against your father and the indictment of nuclear scientist Wen Ho Lee. Is that prejudice even more potent today?

There’s a speech in the play where a character says that 9/11 led to an extended distraction phase, and that once Osama bin Laden and his cronies have been eliminated, America will wake up and realize that while we were spending our time and resources in the Middle East, our real enemies were taking advantage of that window to make themselves more formidable—that America’s true enemy in the 21st century will be China. There are people who are making that same argument now. So, U.S.-China relations are probably going to continue to deteriorate and therefore the fallout on Asian Americans is going to continue to be quite perilous.

It seems that each incarnation of the play resonates with the current zeitgeist.

I think that’s the reason we’re now doing it on Broadway. We recorded an audio version for Audible, which dropped earlier this year, and when we did a table read in preparation for that, the play seemed funnier than it was [before], because the issues that are at the heart of the humor seem so much more in the center of American discourse than they did in 2007.

What are your expectations for Yellow Face now that it’s on Broadway in 2024?

I’m hoping that Yellow Face can make audiences laugh, and through the laughter, think about what it means to try to create an ideal society and to move forward. Also [that the play can capture] the tensions and contradictions, and sometimes absurdities, that happen as we’re trying to create something that hadn’t existed before.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.