“The unsettled state of the industry is an unavoidable talking point these days, but my hope is that our festival, as it has done through its 61-year history, will serve as a reminder that the art of cinema is in robust health,” said Dennis Lim, the New York Film Festival’s director of programing and chair of the main slate selection committee, in a statement last month accompanying the announcement of the titles that will screen as part of the 61st edition of the esteemed festival. From Hollywood’s double strike chaos, to worries about artificial intelligence, to the ongoing threat that streaming poses to the theatrical model—if there was ever a time when we needed that reminder, it’s now.

While all the features in the main slate this year enjoyed their world premiere earlier in the year at Sundance, Berlinale, Cannes, Toronto, and beyond, many will have their North American premiere at the festival. Among them are the opening night film, May December, Todd Haynes’s melodrama about two women whose personal and professional lines blur as they work on a film based a real-life May-December romance; the centerpiece selection, Priscilla, Sofia Coppola’s film about the relationship between teenage Priscilla Presley and Elvis; Hong Sang-soo’s latest, existentially fraught sketches of life in the realm of the mundane, In Our Day and In Water; and the closing night film, Ferrari, Michael Mann’s biopic of automotive icon Enzo Ferrari.

All but six of the films in the festival’s main slate have distribution, and among the most notable are Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s About Dry Grasses, a gorgeously novelistic look at the life of a teacher in the wake of him being accused of inappropriate behavior toward a student; Justine Triet’s Palme d’Or-winning Anatomy of a Fall, a riveting treatise on a relationship facing public scrutiny after a German writer is accused of her husband’s murder; Catherine Breillat’s Last Summer, an unwaveringly sober look at a middle-aged woman’s tryst with her teenaged stepson; and Jonathan Glazer’s hypnotically austere adaptation of the late Martin Amis’s The Zone of Interest, about a Nazi commandant who lives next to Auschwitz with his family.

Among those returning to the festival with new films are Alice Rohrwacher (La Chimera), Aki Kaurismäki (Fallen Leaves), Hamaguchi Ryûsuke (Evil Does Not Exist), Bertrand Bonello (The Beast), and Wim Wenders (Wim Wenders). But perhaps no return is more anticipated than that of Victor Erice, with his first feature in over three decades, Close Your Eyes, an elegy to cinema that revolves around the mysterious disappearance of a famous actor during a film shoot.

The festival’s noteworthy sidebars include Spotlight, a showcase of the season’s most anticipated and significant films (among them Bradley Cooper’s Maestro, Harmony Korine’s Aggro Dr1ft, Miyazaki Hayao’s The Boy and the Heron, Richard Linklater’s Hit Man, Frederick Wiseman’s Menus-Plaisirs Les Troisgros, and Nathan Fielder and Benny Safdie’s The Curse); Currents, which seeks to place an emphasis on “new and innovative forms and voices,” as proven by such works as Eduardo Williams’s The Human Surge 3, Joanna Arnow’s The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Passed, and Pham Tien An’s Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell, Pierre Creton’s A Prince, and Rosine Mbakam’s Mambar Pierrette; and Revivals, a generous selection of digitally remastered, restored, and preserved films (among them Manoel de Oliveira’s Abraham’s Valley, Tewfik Saleh’s The Dupes, Nancy Savoca’s Household Saints, Abel Gance’s La Roue, and Jean Renoir’s The Woman on the Beach). Ed Gonzalez

For full reviews of the films in this year’s lineup, click on the links in the capsules below. (Titles will be added across the upcoming weeks.) For a complete schedule of films, screening times, and ticket information, visit Film at Lincoln Center.

About Dry Grasses (Nuri Bilge Ceylan)

About Dry Grasses primarily concerns a complaint about transgressive behavior by Samet (Deniz Celiloglu) toward one of his female students, 14-year-old Sevim (Ece Bagci), with whom he’s nurtured a caring bond within an institution where any expression of affection would be fundamentally at odds with its pedagogy and ethos. But Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s novelist’s ability to interweave interlocking narrative layers is such that he keeps the film from ever seeming topical. The institutional drama is only one of Samet’s preoccupations, along with the inability to find an audience for his insightful musings, an outlet for his artistic needs, a remedy for desolation and the suspicion of having botched his existence. Hence the accuracy and pointed irony of the film’s English title. About Dry Grasses is just as much about the harshness of a landscape, which mirrors the spirit of its inhabitants, as it is about a barrage of much more elusive things, rendered tangible by an incredible aesthete’s hands. Diego Semerene

Aggro Dr1ft (Harmony Korine)

Harmony Korine’s Aggro Dr1ft cedes control of its images to pure vibes. The film was shot entirely in thermal vision, resulting in a hallucinatory aesthetic of neon colors that simultaneously assaults and seduces the senses. Coupled with an aggressive electronic soundscape, the film is a Miami Vice-on-acid stupor that’s less concerned with antiquated notions of coherent storytelling than in transporting (or perhaps banishing) audiences into another physiological realm altogether. Whether Korine’s vaporwave fever dream actually means anything at all seems beside the point. The totality of Aggro Dr1ft’s audiovisual experience acts like a serotonin shot to the brain the longer one sits with it. It may indeed be the perfect cinematic representation of our current media landscape, adapting to our collective brain rot from being terminally online instead of fighting against it. Mark Hanson

All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt (Raven Jackson)

The first image in All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt—a close-up of a hand squeezing a freshly caught fish, its reflective scales mirrored by the twinkling, gauzy light captured on 35mm—quickly immerses us in the film’s world. The relationship between bodies and the natural world that surrounds them, mediated by the physical properties of film, is central to Raven Jackson’s work. As the scene progresses, the camera’s focus remains on what may seem like its incidental textures, tracking the interplay of skin, earth, and water as if they were brushstrokes on a canvas. The elemental poeticism of these images is evidence of Jackson’s promise as a filmmaker, and yet this opening sequence also points to why All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt is a limited showcase for her talents. Essentially all of the film’s aesthetic, thematic, and tonal range can be distilled to those few shots, and while they hit a lovely note, the impact of the deceptively ambitious narrative is limited by its unwillingness to deviate from that note. Brad Hanford

All of Us Strangers (Andrew Haigh)

When focusing on Adam (Andrew Scott) and Harry’s (Paul Mescal) sensual and spiritual connection, Andrew Haigh allows himself to put aside some of the magical realism of All of Us Strangers and rediscover the magic of realism that powered such incisive love stories as Weekend and 45 Years. The seduction leading up to Adam and Harry’s first sexual encounter is as poignant as any scene in Haigh’s filmography. As the two men struggle to find the verbal and physical language to express what they both want but cannot articulate, the scene proceeds with tactile attention to each tentative shift in their demeanor. While no moment that follows is nearly as sensational, Mescal’s extraordinary capacity for empathetic, reactive listening leaves his sections of the film littered with gently accentuating grace notes. Marshall Shaffer

Anatomy of a Fall (Justine Triet)

At first, it seems like Justine Triet’s Palme d’Or-winning Anatomy of a Fall may turn into a courtroom spin on Basic Instinct. Like Sharon Stone’s Catherine Tramell, Sandra (Sandra Hüller) is a famous novelist whose books seem to contain troubling portents of the crime she’s accused of. Coupled with her outwardly cold demeanor, the film baits us into thinking she could be a criminal mastermind hiding in plain sight. But as the exhaustive courtroom drama at its center proceeds, it’s clear that Triet’s film has more on its mind than the simple question of Sandra’s innocence or guilt, a position that becomes more or less clear far before the final verdict is handed down. At its best, Anatomy of a Fall is nothing less than a rigorous modern treatise on the knotty interpersonal dynamics of long-term relationships and how conveniently they can be distorted when exposed to public scrutiny. Hanson

The Beast (Bertrand Bonello)

We’re all products of our time and circumstance, but how frequently do we push back against the forces—on the beasts both real and imagined—that keep us in anonymizing check? And, having taken such risks, how often do our own stories still end in tragedy? But then again, is the endpoint, our endpoint, the true crux of the matter? A line from Henry James’s 1903 novella The Beast in the Jungle, the loose inspiration for the disquieting The Beast, illuminates what is likely writer-director Bertrand Bonello’s main goal: “It wouldn’t have been failure to be bankrupt, dishonored, pilloried, hanged; it was failure not to be anything.” What the film most acutely captures, as its sprawling canvas expands and contracts before us, is the ceaseless cycle of two people failing to be over several lifetimes, in certain instances because of circumstances beyond their control, and in others because of their own purposeful inertia. Keith Uhlich

The Boy and the Heron (Miyazaki Hayao)

One of the most vital skills an animator can hone is a sense for how gravity will bear down on their subjects in realistic and legible ways. A character who weighs nothing appears stripped of physicality, and we regard them, consciously or otherwise, as invulnerable. Miyazaki Hayao, over the past half-century, has conquered gravity. His drawings feel like people because they move like people; they’re believable because they’re capable of being hurt. Never is this more apparent than when two of his characters embrace, the total catharsis of human bodies colliding expressed in a tight knot of stumbling feet and clasped arms. This ability to render subjects with such convincing tactility is only one reason why Miyazaki is possibly our greatest living animator, and his latest, The Boy and the Heron—a fable about, among other things, the cost of searching for truth in the unreal—is all the more resonant for it. Cole Kronman

La Chimera (Alice Rohrwacher)

In Alice Rohrwacher’s La Chimera, though, the importance of time is seemingly felt by everyone, suggesting a great sinkhole beneath the feet of the film’s characters, who make note of the fact that even as they justify their looting of ancient artifacts as reclamation from an extinct people that one day they, too, may be looted by the civilization that takes their place. That all brings a melancholic tinge to a largely satirical film, which ties back to Arthur’s (Josh O’Connor) discontent. Part of his frostiness can be attributed to his past relationship to Beniamina (Yile Vianello). She’s only glimpsed in a series of wistful flashbacks—and they’re so dreamy that one wonders if the woman was ever real. Gradually, she becomes just another ghost in this land of the dead, a sobering reminder to O’Connor’s treasure hunter that even the living become little more than a faint memory of themselves in the places they once called home. Jake Cole

Close Your Eyes (Victor Erice)

After three decades and a smattering of shorts, Close Your Eyes marks Victor Erice’s return to—and reckoning with—feature filmmaking. Its opening scene, set in an ivy-ensnared chateau in rural 1940s France, seems of a piece with the rest of his work: softly lit, prudently edited, and shot on velvety celluloid. Then, suddenly, it ends. This isn’t Close Your Eyes. Rather, it’s an excerpt from The Farewell Gaze, a film-within-a-film that was left unfinished in the early ’90s following the unexplained disappearance of lead actor Julio Arenas (Jose Coronado). In a stark, digitally shot 2012, the film’s aging director, Miguel Garay (Manolo Solo), agrees to take part in a television special about Julio, thrusting himself back into a mystery he’s spent 20 years trying to forget. On its most basic level, Close Your Eyes functions as a stirring detective story. But its true interests lie not in unspooling Julio’s past so much as in reckoning with the ways those connected to him have also, in their own manner, begun fading away. Kronman

The Delinquents (Rodrigo Moreno)

The best capers are endowed with a professional gambler’s spirit of self-assured play, and this mischievousness is both taken to logical extremes and given a less flashy treatment in Rodrigo Moreno’s The Delinquents. The film constantly toys with its audience, deploying genre cues only to sidestep their expected payoffs and moral resolutions. Whether one interprets the routes that it takes as relatively frivolous fun or serious arthouse theme-making hardly affects the pleasure of watching it. That distinction is just one of many that are defied in a film that treats the very notion of identity like an easily foiled con man. The Delinquents alternatingly dares the viewer to read it as a caper, a moral parable, a comedy of coincidences, and an existential probe. And the confrontation with the meaninglessness of it all is presented with a spirit of levity, with those doing the confronting coming across more like haps than heroes. Pat Brown

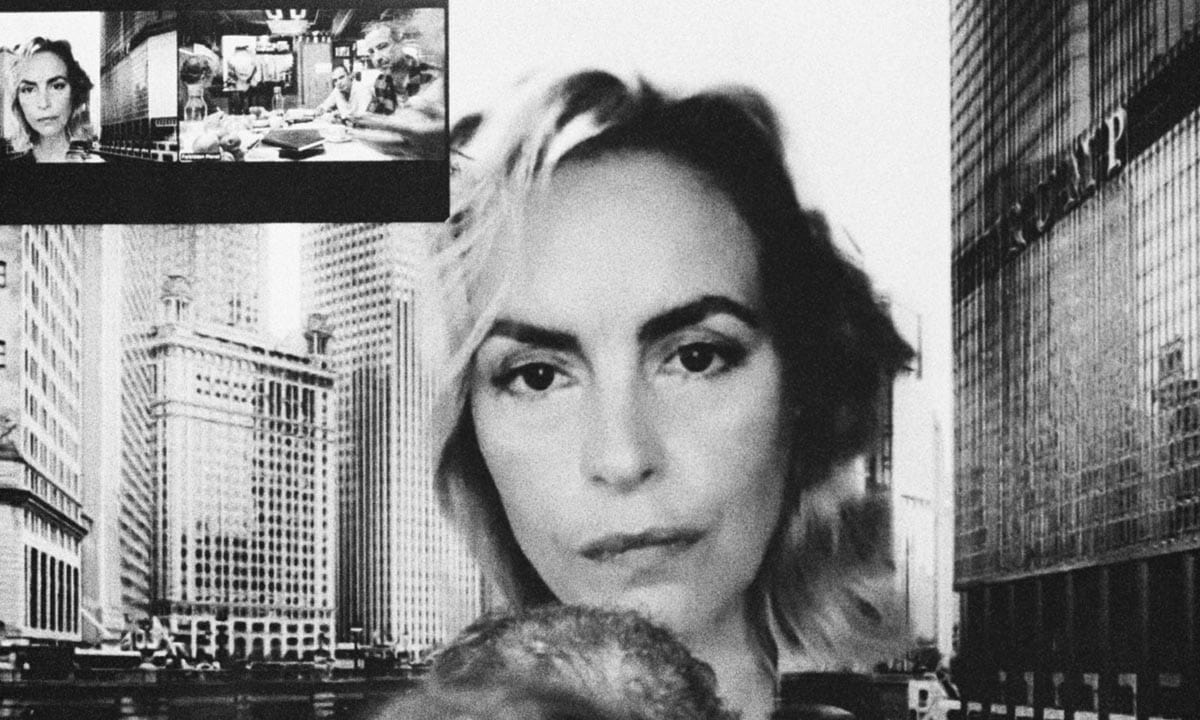

Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World (Radu Jude)

Radu Jude’s Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World presents a nightmare vision of modern life. At the center of it is Angela (Ilinca Manolache), an overworked Uber driver and production assistant who’s tasked with conducting auditions with working-class employees of an Austrian furniture company who were injured on the job. The film’s plot, inasmuch as it has one, ultimately hinges on a man left partially paralyzed in a car-related accident, so it’s fair to say that Jude has vehicles on his mind. His camera observes them as economic necessities, environmental hazards, physical dangers, and, perhaps above all, unsightly detritus cluttering modern cities, embodiments of our dependence on technology. This is a film that listens avidly to what a cross section of ordinary citizens have to say about the war in Ukraine, Putin, Viktor Orbán, Jewish and Romani people, poverty, exploitation, and any other subject that would come up naturally in the course of visiting people in their homes. Seth Katz

Eureka (Lisandro Alonso)

In Eureka, the way in which Lisandro Alonso transitions from Murphy’s (Viggo Mortensen) roaring rampage of revenge to a more disquietingly modern chronicle of a South Dakota reservation policewoman, Alaina (Alaina Clifford), and her sweet, increasingly disaffected niece, Sadie (Sadie Lapointe), is so brilliant and pointed that it’s best to experience it unspoiled. Ditto how the film’s concluding section emerges out of an apparent transcendence of space and time, the focus transposed to an ambiguously South American locale. The South Dakota scenes, in which Alaina moves grimly between drug dens and domestic disputes while Sadie does her level best to connect with everyone from a jailed family member to a naively well-meaning movie actress, are the verisimilar heart of Eureka. The vengeance western and the South American love story, by contrast, are myth-tinged bookends that provocatively grapple with how a given culture’s histories are exploited, packaged, and sold. Uhlich

Evil Does Not Exist (Hamaguchi Ryûsuke)

The forest is a pivotal part of Evil Does Not Exist’s chief setting, Mizubiki Village, a small and isolated countryside community that’s far enough from Tokyo to offer a relief from the clutter and freneticism of city life but close enough to be easily reachable by city folk. Precisely because it’s so beautiful, the community is destined to be gobbled up by developers as a vacation paradise for the wealthy, and Hamaguchi Ryûsuke’s elliptical narrative charts the beginning of this invasion. Curtailing his narratives, seizing up his action, which he foreshadows with the clipped-off score and strange tracking shots, Hamaguchi forces us to reckon with the industrialization of nature—and stew in it. Evil Does Not Exist is a politically engaged act of coitus interruptus, then, though you may not be convinced that Hamaguchi’s new interest in theme over character is a wonderful development in the long run. Preachers are a dime a dozen, while true humanists are as endangered as the woods of Mizubiki Village. Chuck Bowen

Fallen Leaves (Aki Kaurismäki)

Aki Kaurismäki’s Fallen Leaves is built around crosscutting between two narrative strands. In one, the defeatist Holappa (Jussi Vatanen) tries to hang on to a job sandblasting large metalware while sneaking swigs of vodka. In the other, the headstrong Ansa (Alma Pöysti) contends with bureaucratic nonsense and bad luck at a string of dead-end jobs. The film isn’t particularly complicated, but it’s deeply alert to the sensory pleasures of the world, which is what elevates it above the miserabilism latent in its scenario. And in an amusing tribute from one iconoclastic filmmaker to another, Kaurismäki sets Ansa and Holappa’s first date at a screening of Jim Jarmusch’s The Dead Don’t Die, a film that depicts a zombie invasion that brings a bored, anesthetized populace to the brink of extinction. That the budding lovers still leave the theater in a rare state of euphoria indicates Kaurismäki’s abiding belief that not all is lost if art and beauty can still surround us in unlikely places. Carson Lund

The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Passed (Joanna Arnow)

In The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Passed, writer-director-star Joanna Arnow plays Ann, a thirtysomething woman in a long-term BDSM relationship with the much older Allen (Scott Cohen). “I love how you don’t care if I get off,” Ann coos to him at the start of the film. “It’s like I don’t even exist.” While this moment immediately establishing the playful rules of Ann and Allen’s sexual agreement, Arnow also hits on an apt metaphor for the existential crisis of so many modern millennials: that they’re exposed and ignored in an unforgiving social climate still dominated by older generations. In her first feature, Arnow, who speaks in an unwavering deadpan tone throughout, crafts a style that could be described as equal parts Girls and Napoleon Dynamite. Arnow’s dry sense of humor is particularly apparent in the scenes between Ann and Allen, piercing the provocative mystique of a BDSM relationship by displaying their sexual exploits in an exceedingly monotonous way. Hanson

Ferrari (Michael Mann)

The first part of Michael Mann’s film follows Enzo Ferrari (Adam Driver) as he attends to tasks ranging from the mundane to the grief-stricken to the tempestuous. Through it all, Ferrari does his best to maintain the steely look and demeanor that becomes many a Mann protagonist. An impeccably tailored suit is utilized like armor. All words spoken are terse and to the point. Emotion is never on display publicly, and only reluctantly in private. It’s all a pose—but to the dual ends of endurance and survival, as Ferrari’s fortunes are waning. His namesake company is near bankruptcy, and the two lives that he leads, the one with Lina (Shailene Woodley), the woman he loves, and the one with Laura (Penélope Cruz), his wife and co-partner in business, are on a collision course. Cruz’s Laura is a primal force of rage and regret who, in Ferrari’s sensational penultimate scene, battles her standoffish spouse to a smoldering detente. Their confrontation is the harrowingly human analog to the film’s virtuoso vehicular mayhem. Uhlich

Foe (Garth Davis)

In the dystopia of Foe, new “self-determinative” lifeforms are conceived to take on dirty work in a ravaged land. They’re first introduced to us as an idea via the opening title card, which informs us that Earth’s natural and fertile resources, like water and soil, will become rare and valuable commodities later this century. Then they’re presented as the solution to marital loneliness, such as in the case of Junior (Paul Mescal) being drafted to try a government-funded space station out as a new home while his wife, Henrietta (Saoirse Ronan), stays behind on their farm. The notion of the fear of being replaced, especially in the context of a relationship and the uncertainty about one’s selfhood, is compelling in its universality. But Foe’s screenplay is so rotely written that its clichés come to feel like a virus that spreads to every other component of the film. The desolate exteriors are photographed in ever-swirling motions, the infinite stretches of desert suggesting as much a knockoff of a Terrence Malick film. Kyle Turner

Green Border (Agnieszka Holland)

The medium is the message in Agnieszka Holland’s Green Border, a piece of political cinema so freshly ripped from the headlines that you can still feel the jagged edges. Agnieszka Holland shot the film, which chronicles the wide ripple effects of a 2021 surge of asylum seekers along the Polish-Belarusian border, in just 23 days in March of this year and had it ready for fall festivals mere months later. In the end, her sense of propulsive, incandescent outrage is both the project’s reason for existence and its strongest attribute. Holland resists the impulse for urgency to trump all aesthetic considerations. Green Border moves beyond documentary-style realism as a shorthand for authenticity, and it’s at its most gut-wrenching when Tomek Naumiuk’s agile camerawork captures bodies in frequent, frightening motion, as well as the illusory sense of security that those bodies feel in moments of rest. Shaffer

Here (Bas Devos)

Here is as delicate and unobtrusive a film as Bad Devos’s previous cinematic journey through Brussels, Ghost Tropic. The story gently, elliptically slides from setting to setting as Stefan (Stefan Gota), a Romanian construction worker on the cusp of his summer vacation, delivers containers of soup whipped up from the remaining fresh food in his fridge to his friends around town. His journey overlaps and eventually intersects with that of Shuxiu (Liyo Gong), a Chinese-Belgian botanist whose musings on the pseudo-relationship between words and things begins in voiceover some minutes before she actually appears in the film. Establishing a deeper connection with the world appears to be a potential cure for what ails Stefan. Here presents this theme with a modesty that seems to radiate from Stefan himself, offering his world to us through rich, dreamy imagery and with an endearing simplicity. Brown

Hit Man (Richard Linklater)

With Richard Linklater’s Hit Man, Glen Powell has been offered a plum opportunity to shape his image into something more complicated and often poignant. Powell stars as Gary Johnson, a philosophy professor at the University of New Orleans who moonlights as a pretend hitman in sting operations. That premise may seem far-fetched, but the script gives a logical pathway for Johnson’s nerdy tech hobby to seem appealing to the Nola police department’s surveillance teams. And, also, this story mostly really happened. As early as Dazed & Confused, Linklater has been most preoccupied with the self and identity and their coherence and mutability. Many of Linklater’s films are united by their celebration of the pretentious in its etymological meaning of “playing pretend.” With Hit Man, he and Powell take this further by demonstrating that acting isn’t just entertainment or art—it’s also a fundamental part of our lives. Zach Lewis

The Human Surge 3 (Eduardo Williams)

Exhibiting a deliberately fragmentary aesthetic that sought to emulate the context-free disorientation of life mediated through laptops and phone screens, Eduardo Williams’s The Human Surge earned him the Golden Leopard at 2016’s Locarno Film Festival, as well as no small amount of bemusement and scorn from other quarters. The idea that such an obtuse experimental work could have any franchise potential inspired the jokey title of the Argentine filmmaker’s latest effort, The Human Surge 3. Though mostly unrelated to its predecessor, the film shares its jarring, hyperlinked structure and focus on the leisure time and everyday routines of unmoored, underemployed youths in liminal settings around the world. David Robb

In Our Day (Hong Sang-soo)

Hong Sang-soo’s In Our Day is composed of two alternating strands, both pivoting on conversations between artists and their acolytes. The film has no plot in the conventional sense, even by Hong’s spare standards, and the audacious structural gamesmanship of films like Walk Up has been abandoned. In Our Day is meant to feel tossed-off, though Hong’s braiding of scenes—by echoes, symbols, and subjects—is characteristically deliberate. The uninitiated may find In Our Day baffling or uneventful, as inscrutability is a risk that Hong is willing to run for his art, but for the admirer the familiarity of Hong’s subjects and patterns is pleasing and reflective of a working ethos so obsessive that it’s become a life philosophy. Hong keeps chipping away at the mandates of commercial narrative cinema, fashioning a radical cinema aesthetic that abounds in the fleeting observational textures of poetry or journals. Bowen

Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell (Pham Tien An)

Compared to his numbed reaction to the present, Thien (Le Phong Vu) finds motivation in retracing the past he left behind when he moved to Saigon, and Pham Tien An’s Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell patiently observes him rekindling prior relationships in his rural hometown, whether checking in with village elders or running into an ex-girlfriend (Nguyen Thi Truc Quynh), who’s since become a nun. One gradually gets the sense that, though the man left his home to get away from a feeling of being suffocated, he feels far more at ease in the realm of nostalgia than he does in the uncertainty of the present moment. Thien may feel cut off from the world, but Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell is deeply in harmony with it, from its masterful sound design that fills in off-screen space with ambient noises, to its observant long takes, to the deference it shows to the wisdom and experience that elders can impart on the young. Cole

In Water (Hong Sang-soo)

Early on, In Water offers a window into Hong Sang-soo’s astonishingly free working methods. An actor turned aspiring director, Seoung-mo (Shin Seok-ho), scouts an alleyway with his cameraman, Sang-guk (Ha Seong-guk), and actress, Nam-Hee (Kim Seung-yun). Throughout the sequence, Hong shows the audience how he hides his artfulness in plain sight, working In Water’s formal DNA into its very narrative. Such sequences of transcendent minimalism suggest Picasso knocking off a sketch on a piece of paper in a matter of seconds. At times, it’s as if Hong is daring you to call his bluff, contesting whether or not In Water is even a film. Perhaps he even wants us to call him out. And yet, his compositions are hauntingly beautiful. Hong really seems able to make intensely personal cinema out of anything, and perhaps, rather than Picasso, he’s the filmmaking equivalent of the chef who can turn a piece of stale bread, some rotten fruit, and a few odds and ends in the pantry into a revelatory dessert. Bowen

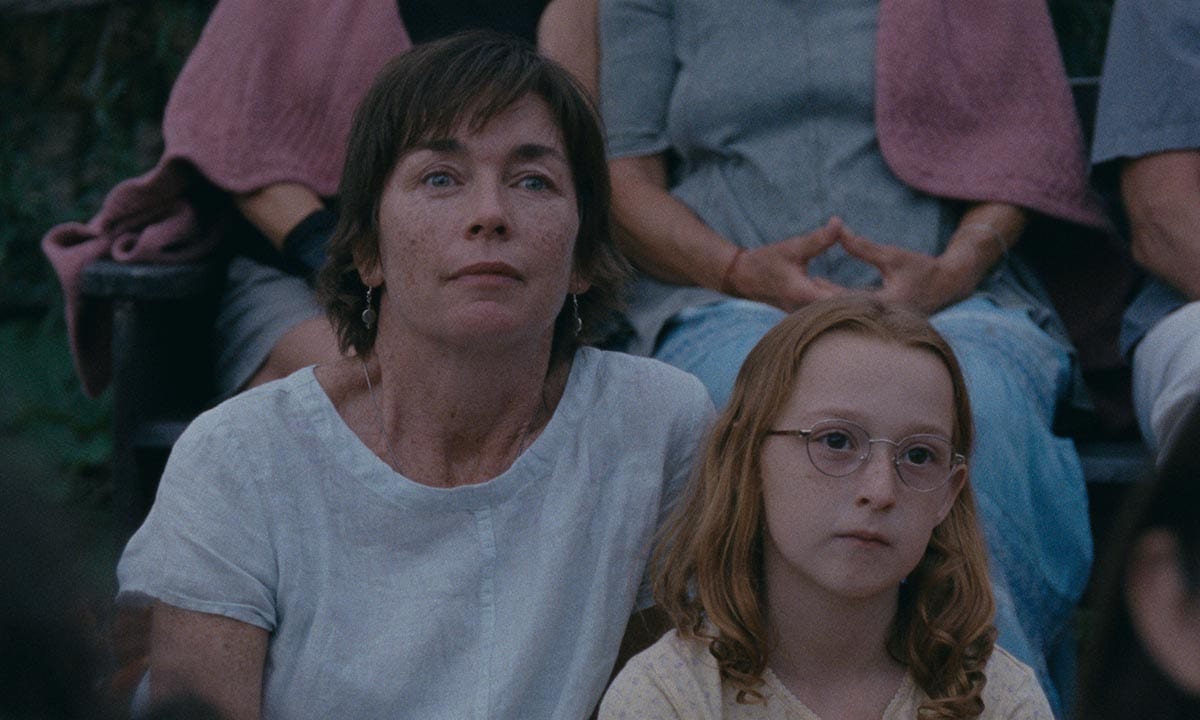

Janet Planet (Annie Baker)

The plot of Annie Baker’s quiet and often moving feature directorial debut, Janet Planet, details the bond between 11-year-old Lacy (Zoe Ziegler) and her acupuncturist mother, Janet (Julianne Nicholson), in rural Western Massachusetts in the summer of 1991 just before Lacy enters the sixth grade. The closest that the film comes to dramatic conflict lies in its portrait of the revolving door of love interests and friends that make up its three “acts.” It’s primarily through Lacy’s shifting perspective that we see her mother and those other characters, with each encounter either bringing her closer to Janet or threatening to tear them apart. As has been typical of Baker as a playwright, though, instead of relying on dramatic confrontations or major plot turns, she homes in on small details to illuminate her characters’ lives. All of those subtleties accumulate to build a fascinating portrait not only of a fraught mother-daughter relationship, but of the precocious Lacy herself. Kenji Fujishima

Kidnapped (Marco Bellocchio)

Marco Bellocchio treats the Edgardo Mortara case as an unabashed melodrama, one kept at a stress-inducing simmer with occasional surges of operatic emotion. The key scene comes early, when the freshly abducted Edgardo—played by Enea Sala as a child and Leonardo Maltese as an adult—is loaded onto a boat by his captors. He’s been a screaming wreck up to this point, but as Francesco DiGiacomo’s camera holds on his face, it stiffens into a chillingly opaque expression. Ripped from his familiar life, the young Mortara has become a suggestible non-person, more readily able to be molded by whoever proves to be the prevailing influence. Kidnapped may sometimes tread a little too close to a palatable prestige drama. Yet as in his late-career masterwork, The Traitor, Bellocchio often uses middlebrow signifiers as aesthetic Trojan Horses, lulling his audience just enough so that the physical and psychological violence, when it comes, hits with a brute force that feels equally rooted in cinema and theater. Uhlich

The Killer (David Fincher)

The Killer is probably David Fincher’s most lightweight literary adaptation to date. This comparatively barebones action thriller has none of the social commentary or pop psychology that color The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and Gone Girl and their page-turning source material, instead following a titular, unnamed hitman (Michael Fassbender) and his efforts to cover his tracks after a botched contract turns him and his girlfriend (Sophie Charlotte) into the new targets of his paymasters. Though The Killer does touch on some weighty themes related to death and fate, particularly in its most lyrical scene where Fassbender’s character has a snowbound showdown with a glamorous, nihilistic fellow assassin (Tilda Swinton), Fincher largely applies his calculating approach in service of a straightforwardly entertaining film, and while it might not offer much in the way of originality or depth, it’s undeniably effective and refreshingly unafraid to embrace its own shallowness. Robb

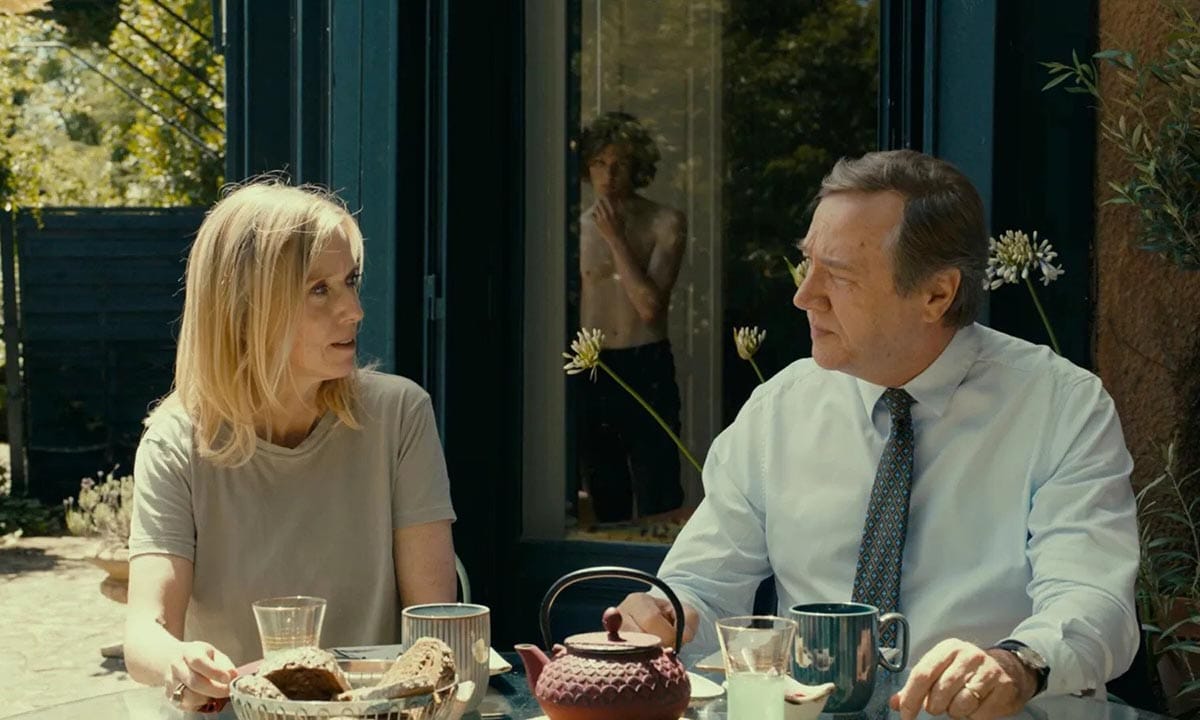

Last Summer (Catherine Breillat)

In Last Summer, Catherine Breillat brings her icy, unwaveringly sober sensibilities to one of the most common of American pop cultural sex fantasies: a teenager’s tryst with a MILF. At their home in the suburbs of Paris, we see Anne (Léa Drucker) with her older husband, Pierre (Olivier Rabourdin), who’s successful but scans as dull and schlubby when compared to his trim and attractive wife. If we know Last Summer’s narrative ahead of time, we may feel as if an equation is being established that’s typical of older-woman, younger-man sex fantasies: that a boring husband gives a wife license to get her groove back elsewhere. But we’d be wrong. Elsewhere, Breillat doesn’t mar the realtionship between Ann and Théo (Samuel Kircher), Pierre’s 17-year-old son, in the harlequin clichés a daydream. The reality of this situation is always compacted by Breillat’s committed and very pointed objectivity. No one in Last Summer is sentimentalized, and Breillat denies neither the ickiness of this affair nor its potential pull. Bowen

Maestro (Bradley Cooper)

Maybe no biopic, however sensitively done, can come close to encompassing the entirety of Leonard Bernstein’s life. This was a man so filled with passion for music in all its forms that he couldn’t help but let it out not only in the music he composed, but also on the podium as a conductor and throughout his teaching. But Bradley Cooper’s failure to come up with a film that does such a charismatic, mercurial, and complicated figure full justice is especially disappointing. With Maestro, he’s essentially reduced Bernstein’s boundary-pushing life and legacy to the sum total of its most accessible (read: audience-friendly) elements: his interpersonal relationships. To that end, Cooper mostly relegates Bernstein’s art to the sidelines, perhaps on the assumption that his accomplishments are already widely known. Such a fundamental failing on Maestro’s part may well lead one to the broader conclusion that perhaps not all Great Men need to have biopics made about them. Fujishima

May December (Todd Haynes)

Loosely based on the tabloid scandal of Mary Kay Letourneau, Todd Haynes’s May December examines real-world events through the lens of mass media with a wry humor that masks profoundly complex and painful undercurrents of emotion. The subject matter is certainly fraught, especially at a time when so much of our collective imagination has been consumed by compounding and corrosive obsessions with both age-gap relationships (or outright pedophilia) and the cynical content-ification of real-life crimes and tragedies. The addition of Natalie Portman’s character, then, is the masterstroke that affords the filmmakers the distance to investigate and comment not only on the relationship between Gracie (Julianne Moore) and Joe (Charles Melton), but also on the hidden desires and neuroses that drive our own insatiable desire to turn real-life social pariahs into on-screen subjects. Hanford

Music (Angela Schanelec)

Crudely summarized, Music is a modern re-telling of Oedipus Rex. Angela Schanelec composes her shots with a beautiful but harsh precision, holding them longer than even the contemporary masters of slow cinema, but the primary action always seems to be just off screen, either spatially or temporally. In fact, the most impressive component of this style is how much she’s able to get the viewer to piece together, and how captivating it can all be. It’s as if she wants us to play the absent film in our head during the long stretches of silence that begin and end virtually every shot. We’re invited not just to draw the connections between the events of the film and the Oedipus myth, but also to read between the lines, to infer story from indirect signifiers. Initially, more than mere fun, this makes for surprisingly affecting storytelling, but once you’ve figured out how to play, the game begins to feel a bit, well, ancient. Brown

Menus-Plaisirs Les Troisgros (Frederick Wiseman)

In Menus-Plaisirs Les Troisgros, Frederick Wiseman settles into a three-star Michelin eatery in Roanne, France, and unearths another of his temples of contemplation. In a kitchen populated by working-class heroes looking to prove themselves, hysterics might seem inevitable, but here the chefs and other artists and technicians seem to take their brilliance as a given, seeking to coax it to its fullest expression. The sophisticated feng shui of La Maison Troisgros meshes intimately with Wiseman’s beautifully lucid long takes, and the filmmaker is alive to the class tensions that separate La Maison Troisgros’s kitchen from that of a less rarefied restaurant. Wiseman has made a career documenting class in various social systems, but he allows such differences to remain implicit. An artist himself, Wiseman is less interested in landing classist broadsides than in honoring the internal biorhythms of the realm surrounding him. Bowen

Orlando, My Political Biography (Paul B. Preciado)

Paul B. Preciado’s interlacing of the personal, the interpersonal, and the political is intricate and evocative in ways that often belie his no-spectacle staging and no-frills camerawork. Even so, Orlando, My Political Biography’s pointed disregard for straight filmmaking tends more toward academic discourse than rambunctious subversion. Though the opening titles claim that what we’re watching has been “freely adapted” from Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, the film languishes in an undefinable interstitial space, floating between fiction and essay film. It brings in members of French trans communities, ostensibly to act out scenes from the book, but has each of them step in and out of character, intermingling their own stories with Woolf’s nine-decade-old rendition of non-binarism. The scenes performed are thus at once adaptation and commentary, and this indefinability has clear thematic resonance. Brown

Perfect Days (Wim Wenders)

With Perfect Days, Wim Wenders aims for simplicity, following a middle-aged man, Hirayama (Yakusho Kôji), as he goes about his day cleaning Tokyo’s toilets, taking pictures of trees, listening to American rock, reading classic literature, and savoring the humble sources of day-to-day affirmation that we tend to take for granted. The film wants to be an invitingly human movie that homes in intensely on the little moments of a man’s life so as to unearth universal truths. A few scenes late in Perfect Days hint at trauma that Hirayama may be suppressing, but Wenders generally sees him as a man without warts. He does nothing that would disrupt the filmmaker’s fetishizing of his immaculate grace. In other words, Wenders hasn’t quite escaped one of his straitjackets: characters that scan only as symbols. There’s even something cutesy and self-congratulatory about an act as simple as how Hirayama drinks ice water after work at his favorite restaurant—yet another testament to the man’s purity. Bowen

Picture of Ghosts (Kleber Mendonça Filho)

At the heart of Kleber Mendonça Filho’s argument in Pictures of Ghosts is how much of the resources and capital that allowed for a thriving cinephilic culture in Recife, Brazil, was stripped away in the 1970s and ’80s, and committed instead to making the city into a tourist destination for wealthy foreigners. One of the first pieces of archival footage we see features Janet Leigh and Tony Curtis on vacation in the city (with little Jamie Lee in tow), a flash of Hollywood glitz that carries uncomfortable associations in context. At one point, Mendonça Filho comments that “fiction films make the best documentaries,” which sounds like a banal truism until the final scene, an unexpected departure from nonfiction that slyly implicates the filmmaker in his own commentary. As always with Mendonça Filho, to reflect reality isn’t enough, as cinema has to find its own truth, even if it takes some imagination to get there. Hanford

The Pigeon Tunnel (Errol Morris)

Less a last will and testament than a mischievously mutual final troll, Errol Morris’s The Pigeon Tunnel sees both its director and its subject, the late spy novelist John le Carré, engage in a circuitous dialogue, shot over four days near the end of 2019, that’s as charming and playful as it is oblique and ominous. There were plenty of affairs in his love life, a subject he cheekily declines to discuss here, as well as betrayals of colleagues and confidants for which he doesn’t express remorse so much as a retrospective curiosity about his actions, as if he was a pathologist prematurely examining his own corpse. Yet plenty of his deceit was, of course, sanctioned by his own government. All the willful obfuscation at times makes The Pigeon Tunnel feel slighter than Morris’s best work, and the slow-mo-tinged re-creations he employs in service to Le Carré’s words are a bit too reliant on dodgy CGI. Yet the sense of getting nowhere in particular proves to be crucial toward grasping Le Carré in all his impish glory. Uhlich

Poor Things (Yorgos Lanthimos)

In Yorgos Lanthimos’s Poor Things, as unpleasant as life can be, especially for a woman, there’s still hope in the sheer and bizarre splendor of it all. The film is adapted by Tony McNamara from Alasdair Gray’s novel of the same name, which is inspired by Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and its interrogation of Victorian repression and hunger for the power of God. The film abounds in spit takes, incongruous expletive-shouting, and slapstick—comic bits that recall Monty Python as much as Lanthimos’s earlier work. The Greek weird auteur’s pristinely dark humor may be softening, but he still demonstrates an interesting range when mining things for laughs here, be it visual gags, crassness, or line readings. As imaginative as the film’s comedy can be, though, its greatest asset is Emma Stone’s ability to situate Bella Baxter, a young woman who’s brought back to life by Dr. Goodwin Baxter (a perfectly Karloffian Willem Dafoe), first as jester, then as the emotional foundation upon which the whole of Poor Things is built. Turner

La Práctica (Martín Rejtman)

Martín Rejtman’s La Práctica fits nicely into his catalog of low-stakes black comedies full of characters who are too busy hanging out to really care about anything else. Throughout, his still camera allows for moments of irony and absurdity to land as lighthearted jokes, such as an affair being revealed by a character walking into frame during breakfast or Gustavo (Esteban Bigliardi), an Argentinian yoga instructor living in Chile, disappearing from the frame as he takes another fall. And despite the characters’ growing intimacy, they all speak in a deadpan manner reminiscent of characters from a Aki Kaurismäki or Jim Jarmusch film, which makes a fellow yoga instructor’s suggestion that Gustavo fix his medical problems with Russian YouTube video exercises sound even more ridiculous than it already does. Such subtle humor is La Práctica’s way of highlighting the follies of a world of regimented self-improvement, in the process reminding us of how absurd and beautiful a mortal life can be. Lewis

Priscilla (Sofia Coppola)

Based on Priscilla Presley’s 1985 biography Elvis and Me, Sofia Coppola’s Priscilla is another impossibly photogenic tale of fame, solitude, material wealth, and female desire in a world that often contrives to deny its existence. Spanning 14 years in the life of Priscilla (Cailee Spaeny), from her meeting Elvis (Jacob Elordi), the rock ‘n’ roll heartthrob she idolized near the army base where he was stationed, to her leaving their lavish Memphis home after the dissolution of their marriage, this is the most ambitious film Coppola has made to date. Unfortunately, its larger scope proves to be something of a hindrance. While her prior efforts tended to focus on just a few places or a forcibly truncated amount of time, lending even the most dramatic incidents an allusive quality and mirroring the sense of dislocation experienced by the characters, Priscilla’s expanded canvas often obscures its emotional subtleties. David Robb

Ryuichi Sakamoto | Opus (Sora Neo)

Many artists appear to discover the power of minimalism in their older age: the beauty of paring their art down to bare essentials, the profundities that come with evoking more by saying less. That appears to be how the late pianist and composer Sakamoto Ryuichi approached his art in the last years of his life before passing earlier this year from throat cancer. The evidence of this can not only be heard in his final studio album, 12, but it can also be heard and seen in his son Sora Neo’s concert documentary Ryuichi Sakamoto | Opus. This, though, is no ordinary concert film, beginning with there being no audience. Sakamoto, having by late 2022 sworn off live concerts as a result of his declining health, decided to perform 20 of his works on a piano in NHK Broadcast Center’s 509 Studio in Japan, with only Sora and a camera crew present to capture it all. In essence, the film boils down to just Sakamoto playing his works on a piano. The result makes for a uniquely affecting last will and testament. Fujishima

The Settlers (Felipe Gálvez)

Felipe Gálvez’s feature-length debut, The Settlers, takes place in an independent Chile at the end of the 19th century that’s still defined by its period of colonization. Any story that directly confronts the wanton brutality of colonization and manifest destiny in the Americas perhaps inevitably draws comparisons to Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, a Grand Guignol of frontier extremity. Alexander MacLennan’s (Mark Stanley) callously detached carnage against indigenous South Americans blatantly recalls some of the more wanton violence of that book, but Gálvez takes an inventively circumspect approach to depicting that slaughter. The Settlers also recalls McCarthy’s sense of pitch-black humor, which is so intense that it threatens to absorb all light. Gálvez’s satire lacerates the contradictions and hypocrisies of European racism and how its convolutions would pit even fellow whites against one another. Cole

The Shadowless Tower (Zhang Lu)

Zhang Lu, who was an established novelist before pursuing filmmaking, handles the parallels between his characters’ out-of-time-ness and the cultural confusion of an evolving state with literary finesse. Moments of contemplative silence between Gu Wentong (Xin Balqing), a divorced father whose life has settled into a dispassionate existence, and Ouyang Wenhui (Hung Yao), a young photographer, take the place of what might have been internal monologues or omniscient third-person narration on the page, letting the nonverbal gestures speak to the film’s ideas. These characters are often framed in doorframes and windows, or reflected in mirrors—subtle indications of how they always feel on the precipice of performing an action that never fully takes place. The Shadowless Tower spends much of its 140-minute neck-deep in ennui, but the tentative efforts at rapprochement between Wentong and his father (Tian Zhuangzhuang) belatedly justify the inviting warmth of Piao Songri’s cinematography as an undercurrent of hope that refuses to accept alienation as a permanent condition of contemporary life. Cole

Strange Way of Life (Pedro Almodóvar)

Strange Way of Life feels tame and flat, given that this was Pedro Almodóvar’s chance to turn the western inside out in his unique way. His penchant for eye-catching production design has often helped him play with the tropes of melodrama, noir, and sex comedy—the sets elaborating upon the director’s goals in exploring how genre is shaped by material space. But this short has no such desire to tinker with how color influences our perception of what a western is or looks like. If the history of the queer western is built on innuendo and a certain kind of subversion, and Almodóvar’s specialty is deranging genre itself, it’s frustrating to encounter something like this that doesn’t take advantage of interrogating the literalism of “queering the western” itself and what that ethos means. The western, with its anxieties about masculinity, modernity, and the natural, is as perfect a place to find the danger of desire blister beneath the desert sun. But Strange Way of Life ends up as unremarkable as any clay-colored rock. Turner

The Sweet East (Sean Price Williams)

It’s not much of a spoiler to say that the final image of Sean Price Williams’s solo feature directorial debut, The Sweet East, is that of Lillian (Talia Ryder) nonchalantly strolling toward and past the camera, a smirk on her face. That’s effectively the whole vibe of the film, an odyssey that traipses through the world of white supremacist academics, PizzaGate conspiracy theorists, self-satisfied filmmakers, mixed-media artists of questionable talent, and religious zealots. For all the tactility of Price Williams’s cinematography, the film is pretty fuzzy on what it wants its national tour of brainless dogma to mean. Lilian drifts from milieu to milieu, sometimes without a phone, sometimes with an ambition of what kind of person she wants to transform into, sometimes with her eye on whatever platform can surveil her at any given moment. But seldom with enough cohesion to pass the movie off as a character study of someone living in, as playwright Matthew Gasda would call it, “the dumbest of times.” Turner

Youth (Spring) (Wang Bing)

Whereas Wang Bing’s 15 Hours seems very much designed to be absorbed in sections in a gallery setting, and Bitter Money scanned as a bleaker portrait of capitalist exploitation, Youth (Spring)’s immersion in the social culture of textile laborers projects mainly a sense of buoyancy and curiosity. An assortment of Mando-pop songs play over tinny speakers as Wang’s subjects engage in both synchronized and syncopated labor, their choreographed hands dancing around sewing machine needles. During these sequences, and without any overt aestheticization, the film sometimes takes on the feel of a movie musical. There’s a tension at work here between mechanical, collective labor and the expression of individualism, which seems continually catalyzed by the musical accompaniment—not only in that it causes workers to break their stoical facades to sing along, but also because the music’s romantic narratives seem to spur the little flirtations and courtships that unfold in front of us on the factory floor. Sam C. Mac

The Zone of Interest (Jonathan Glazer)

Rather than put gruesome imagery of death and cruelty front and center on screen throughout The Zone of Interest, Jonathan Glazer uses the film’s grueling sound design to represent the unfathomable scope of Nazi Germany’s crimes. It’s an aural hell punctuated by rhythmic interludes, courtesy of frequent collaborator Mica Levi, that suggests a dance party in Dante’s Inferno. To heighten the disturbing mood, Lukasz Zal’s camera often places a character in the dead center of the frame, and dollies alongside them as they walk to and fro, channeling the lockstep behind Adolf Hitler. Otherwise, though, it plays the stable voyeur with a lens angle just wide enough to feel unreal. This is no simple political message movie, nor is it even a portrait of one of the most horrific moments in history. Instead, The Zone of Interest is the hellish counterpart to The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, another film about the soulless march of the careerist’s life. Only in Glazer’s version, the march is a goose step. Lewis

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.