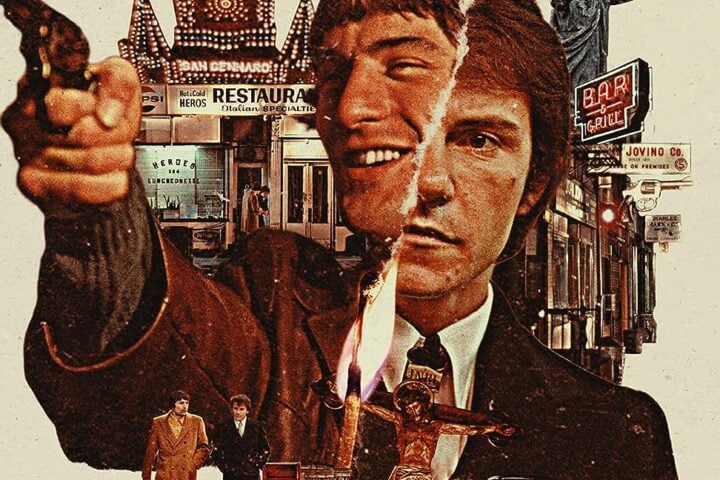

Even by the scuzzy standards of Abel Ferrara’s filmography, Bad Lieutenant is particularly filthy. The film follows the exploits of Harvey Keitel’s unnamed New York City police detective as he nominally investigates the rape of a nun (Frankie Thorn) but largely engages in a series of self-destructive acts involving drugs, alcohol, and abuses of powers. Despite being a Catholic himself, the lieutenant can scarcely show an ounce of sympathy for the nun to his colleagues. Upon hearing of a reward offered for the rapists’ arrest, he explodes, “Girls get raped every day. Now they’re gonna put up 50 Gs just ‘cause these girls wear fucking penguin suits?”

Just beneath this nihilistic surface, however, is a man barely able to tamp down the spiritual crisis that arises not merely from the crime but the victim’s response to it. Not long after the nun returns to her church, she confesses that she knows who violated her but refuses to name them, choosing instead to forgive her transgressors. This show of absolute faith reveals the lieutenant’s lack of his own, and the shame this inspires in him manifests only as yet more rage and self-obliterating harm than he already demonstrates.

Keitel plays the lieutenant with an animalistic intensity that marks him less a lost lamb of God’s flock than a sheep being led to slaughter. He mewls and moans and squeals when he falls into depressive fits, warping his face into an increasingly haggard, sallow state of narcotized deflation and his body language into a defeated slump. Keitel’s performance reaches an absolute peak in the lieutenant’s climactic breakdown inside the nun’s cathedral as he hallucinates a vision of Christ that he castigates for bearing silent witness to the detective’s and others’ suffering before lamenting his weakness to temptations of the flesh and begs forgiveness.

The howling wails with which Keitel delivers these pleas in many ways embodies Ferrara’s approach to filmmaking. For all the gritty, unvarnished nature of the filmmaker’s images and plots, he’s less a realist than an essentialist, blending natural and archly heightened aesthetic registers until they express all sorts of higher truths. Ferrara is regularly likened to a gutter-level Martin Scorsese, but he might equally be called the American Werner Herzog, with Keitel delivering the most Kinski-esque performance of any of the director’s films.

In its own brutal way, Bad Lieutenant is as earnest an interrogation of the implications of Catholic dogma as a lineage of theological dialogue stretching back centuries to the time of Augustine of Hippo. The lieutenant merely acts out physically what others have engaged with as a thought exercise: If we are born sinners only granted salvation by the sacrifice of Jesus, is not a life of sin simply living according to God’s view of His own creation?

Indeed, by that logic, it’s only in offering a path to redemption to such a debauched, lost soul as this man that salvation can be miraculous in the first place. The grace that does come for the lieutenant is hard-won and grimly delivered, suggesting an alternative universe where Flannery O’Connor grew up in Koch-era New York instead of the Jim Crow South.

Image/Sound

Bad Lieutenant’s cinematography hasn’t been well-served on home video, with the naturally lit city exteriors often appearing washed out and soft on DVD editions of the film, as well as on Lionsgate’s 2010 Blu-ray. Kino Lorber’s 4K disc at last presents the film as it should look: not overly saturated but nonetheless crisply textured and balanced between its naturalistic tones and moments of expressionistic color. The boosted brightness of earlier home-video presentations has been replaced with a more accurate contrast that reveals deeper details in close-ups and in backgrounds, as well as richer black levels in dark interiors.

Kino includes a stereo soundtrack and a 5.1 mix, and while the latter adds more depth to exterior shots, it also reveals too much artificial separation between channels, resulting in a few moments of faintly reverberating dialogue. The 2.0 audio sounds just as robust as the surround mix but more naturally blends the elements of the soundtrack. (Sadly, Schoolly D’s “Signifying Rapper” is still blocked from these tracks thanks to a lawsuit over uncleared samples.)

Extras

Kino’s disc comes with an archival Blu-ray commentary track by Abel Ferrara and cinematographer Ken Kelsch, and like all Ferrara commentaries it can be both informative and hair-raising, as the director intersperses his insights on the production and underlying themes with cantankerous rants about his various struggles making and exhibiting the film. The disc also ports over Lionsgate’s retrospective documentary featuring remembrances from cast and crew. New to this edition is an interview with Kelsch, who recalls shooting the film on a paltry budget, and a featurette diving into the locations used for both exterior and interior shots.

Overall

Abel Ferrara’s excoriating exploration of faith and religious guilt finally receives a definitive home-video release that finds the beauty beneath its coat of filth.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.

This release still uses the non-Schoolly D soundtrack. They do not get my money.