“All this filming isn’t healthy,” says blind but perceptive Mrs. Stephens (Maxine Audley) late in Michael Powell’s resolutely disturbing Peeping Tom, and every aspect of the film’s rigorously self-reflexive construction seems to bear her out. From the opening shot of an opening eye, to the final shot of a blank screen swathed in black and blood-red gel lighting, Peeping Tom obsessively examines the social and psychological ramifications of overactive cinephilia. This situates Powell’s film as a direct precursor to later 1960s autocritiques along the lines of Federico Fellini’s 8½, Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up, and Haskell Wexler’s Medium Cool.

Powell and screenwriter Leo Marks originally wanted to make a film about Sigmund Freud and his theories, but word of John Huston’s upcoming Freud biopic put the kibosh on those plans. So instead they came up with the story of Mark Lewis (Carl Boehm), who works days as a focus-puller at a British film studio, with a sideline taking nudie-cutie snapshots for a Soho newsagent, while all along what he really wants is to direct. What he wants to direct is the ultimate documentary about capturing the final paroxysms of fear in the face of death.

Drawing on his wartime training as a cryptographer, Marks salts the script with Freudian concepts in both the verbal and visual registers that have to be decoded by the viewer. But the vein of mordant black humor running through Peeping Tom often makes these references come across like red herrings or cheeky in-jokes, the latter of which brings the film’s more troubling elements into starker relief. And where the dead-serious psychiatrist in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho wraps everything up so very neatly with a single exposition dump, Peeping Tom’s Dr. Rosan (Martin Miller) is a charming little man with a bad sneeze, who manages to put Mark on to the key term scopophilia. His prognosis for a speedy cure is deadpan hilarity.

When Mark shows Helen Stephens (Anna Massey), who lives in the flat below his with her blind mother, some home movies as a strange sort of birthday present, the fact that his famous scientist father is played by none other than Michael Powell himself, with his son Columba standing in for young Mark, only adds another layer of the self-reflexivity to the film. It’s ironic that the father’s behaviorist research into the effects of fear on the already nervous system, using Mark as a handy test subject, is based entirely on observable effects, whereas the script uses Freudian psychology to probe the unseen world of the unconscious.

Mark’s job at a thinly disguised Pinewood Studios (playing itself) allows Powell to ruthlessly satirize certain kinds of British cinema of the period. For one thing, it’s entirely unclear whether The Walls Are Closing In, the film-within-the-film we see Mark working on, will turn out to be a drama or a comedy about kleptomania. The leading lady, Pauline Shields (Shirley Anne Field), can’t even faint convincingly. And the director, Arthur Baden (Esmond Knight), is quite literally blind. But the most cutting depiction is saved for producer Don Jarvis (Michael Goodliffe), modeled on Rank mogul John Davies, with whom Powell had often feuded. Jarvis’s motto pretty much says it all as far as Powell is concerned: “Is it commercial?” You could say that, along with Mark’s unfortunately victims, most aspects of the British film industry gets it in the neck here.

What’s more, the studio setting allows Powell to indulge in an elaborate central set piece that not only reinforces the central themes but also casts a knowing wink back at some of Powell’s earlier works. Mark has recruited a stand-in at the studio, Vivian (Moira Shearer), for a starring role in his documentary project. There’s irony in Powell casting Shearer as a lowly stand-in when, at the time, she was an international star who had been catapulted into the firmament by appearing in Powell and Pressburger’s The Red Shoes, another tale that concerns the tragic results of obsessively pursuing artistic transcendence.

As though to remind us of Shearer’s history with Powell, Viv breaks into an impromptu modern dance number while Mark sets up the lighting. Her stiff-jointed moves just might remind us of Olympia, the automaton she played in Tales of Hoffmann. What follows is a brilliantly reflexive bit where Viv playfully turns the studio’s cumbersome 35mm camera on Mark, who can only respond by aiming his handheld 16mm Bell & Howell at her. Succinctly summarizing the film’s abiding fixation on self-reflection, Mark explains, “I’m shooting you shooting me.”

Mark’s voyeurism seems untethered from conventional notions of beauty. In the cheesecake shoot above the newsagent, Mark is completely bored by having to work with blond bombshell Minnie (Pamela Green, a notorious pinup girl of the period), but he’s immediately smitten by the disfigured visage of Lorraine (Susan Travers), going so far as to switch over from a still camera to his beloved Bell & Howell. And his camera is quite literally an object of desire, something that Anna refers to as “almost another limb,” an appendage Mark endlessly fondles and lovingly fiddles with, never more overtly than with the lingering kiss he bestows on it immediately after Anna gives him a rather chaste peck on the cheek.

But then beauty isn’t what Mark’s ultimately after. Above all else, he wants to bring together love and death in some kind of poetic Liebestod right out of Wagner. This fixation culminates in the final scene where Mark, conducting a perverted sort of Muybridge experiment, sacrifices himself on his camera’s fixed bayonet. It’s frankly orgasmic the way he silkily states, “Helen, I’m afraid!” But does Mark get his money shot? As he succumbs to his all-too literal death drive, the viewer is left bereft, with only a spooled-out film reel, a blank screen, and a childish voice bidding his father goodnight. Mark’s impossible project ends with oblivion, with endless night. We don’t even need a “The End” to know that we’ve arrived.

Image/Sound

The new 4K restoration of Peeping Tom looks phenomenal, a major improvement over the Criterion Collection’s then-impressive DVD release from 1999. The lurid splashes of Eastmancolor that mark Otto Heller’s cinematography are deeper and richer, and the restoration brings out far more of the fine details of the meticulous production design. Grain levels are well-maintained throughout and never get too blocky. As anticipated, the HDR on the 4K disc elevates the colors and fine details by several further degrees. Audio comes in a LPCM mono mix that suitably delivers composer Brian Easdale’s eerie, piano-heavy score.

Extras

This stellar release boasts two well-matched commentary tracks, one from film scholar Laura Mulvey that dates back to Criterion’s 1993 laserdisc edition, and a more recent track by film historian Ian Christie. As expected from the queen of “the male gaze,” Mulvey’s track leans heavily on Freudian psychoanalytic interpretations. However debatable these sorts of analyses can become, the approach makes particular sense here, since director Michael Powell and screenwriter Leo Marks deliberately layered Freudian concepts and terminology into Peeping Tom for audiences to decode. Christie’s track provides a close thematic reading, while also going into lots of details of the film’s production history.

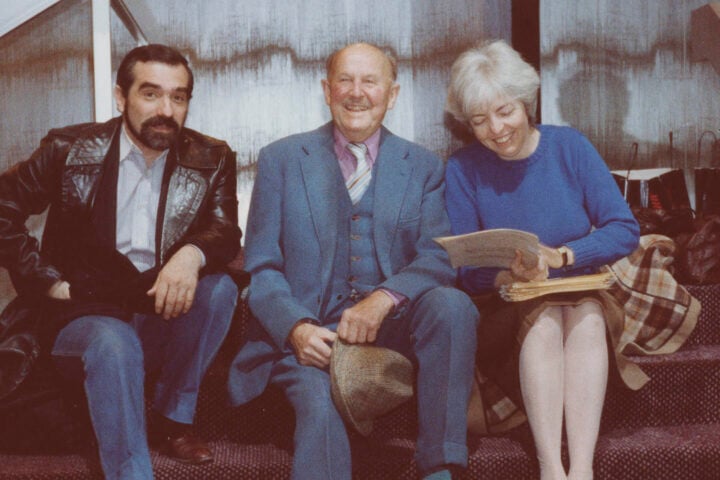

Most of the other supplements have all been ported over from Criterion’s previous Blu-ray release, including a brief introduction from longtime Powell fan Martin Scorsese. Chris Rodley’s “A Very British Psycho” is a fascinating examination of the life and career of Leo Marks, from being raised in a legendary Charing Cross bookstore to working as a cryptographer for MI6 during WWII. It also provides an excellent overview of the film’s production and reception, with lots of talking-head contributions from cast, crew members, and critics of the film.

The extras are rounded out by an interview with Powell’s widow and longtime Scorsese editor Thelma Schoonmaker, a 20-minute profile of the film from 2007, as well as a new piece on the film’s 4K restoration. The enclosed leaflet contains an insightful essay from Megan Abbott that touches on the film’s themes of trauma and voyeurism, its sense of meta-play, and more.

Overall

Michael Powell’s elegant and disturbing Peeping Tom turns its camera eye on an unhealthy obsession with all things cinematic.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.