Most of us know in our bones the sleep-shattering jab of an early-morning alarm and the plummeting sensation of a job interview gone wrong. If Eric Gavel’s Full Time is more of a nail-biter than the thrillers it takes its breakneck pacing from, this can be chalked up to the relatability of its protagonist. Julie (Laure Calamy) is a single mother of two who commutes to Paris from the suburbs in her capacity as head chambermaid at a four-star hotel, while at the same time looking for a job better suited to her university education. The film’s title is quite literal, alluding to the “second shift” that still falls disproportionately on the shoulders of women, often expected to perform hours of unpaid domestic labor after clocking off from work.

Julie’s day-to-day life would be grueling enough were it not for the transit strike that serves as a backdrop to her struggle. It makes her late for work and late to pick up her kids from their nanny, Madame Lusigny (Geneviève Mnich), forcing her to hitchhike or pay for taxis that she can’t afford while she waits for her ex-husband to pay alimony. Still, she views the strikes almost as a rogue weather phenomenon, never blaming them for her troubles but never showing any solidarity either, let alone pausing to consider why she can’t go on strike herself. Instead of trying to organize her workplace, she pins her hopes on a job interview at a marketing firm. In her desperation, she cuts corners and relies on her co-workers to cover for her.

The frenetic editing of scenes that see Julie sprinting from terminal to terminal through seething crowds and traffic jams, barely keeping her cool as further delays and cancellations of service are announced, never relents, and her work routine is shot at the same level of intensity. The pulsing Minimal soundtrack by Irène Drésel matches the rhythm of rapid-fire close-ups showing Julie changing into her uniform, making beds, fluffing pillows, scrubbing toilets, and so on. All of which provides a palpable contrast to the rare scenes in which she gets a breather.

Full Time’s offers an even-handed depiction of its flawed protagonist. Cornered though she is, the individualism that drives Julie’s actions leads to the firing of another single mother, Lydia (Mathilde Weil). A scene at a party suggests that her past reliance on alcohol, as much as anything, lead to her divorce. When she hears a striker interviewed on the radio saying that he hasn’t seen his children in 10 days, it puts her own struggle into perspective.

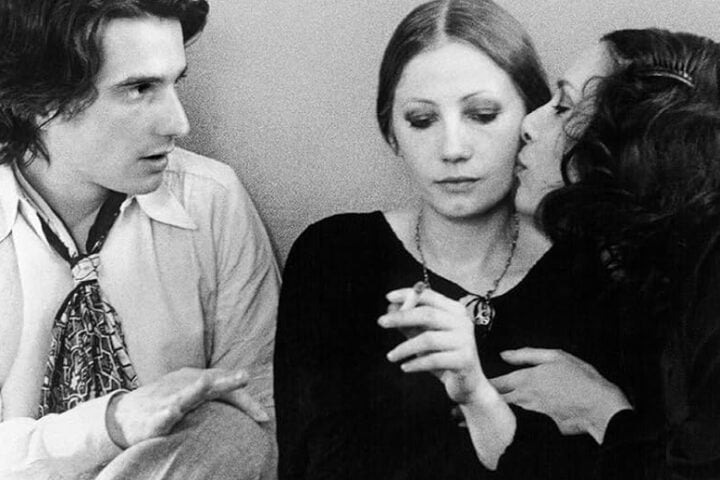

Vincent (Cyril Gueï), the only character in Full Time with any direct relation to the strikes at all, is an ex-military man who gives Julie a lift into Paris on his way to join a supporting march, and later helps her to repair her hot water heater, gently rejects her advances, which he rightly interprets as an act of desperation rather than passion. Here and elsewhere, Calamy’s performance deftly captures the moment-by-moment collapse of Julie’s composure.

The screenplay’s critique of work can only extend so far, framed as it is by Julie’s perspective as a middle-class woman, fallen on hard times but with middle-class aspirations. There’s an ironic edge to the fact that her job transposes the domestic labor she performs at home to a hotel—domestic space in its most alienated form. That both Julie’s boss at the hotel, Sylvie (Anne Suarez), and her job interviewer at the marketing firm, Jeanne (Lucie Gallo), are women suggests that it’s capitalism, not sexism merely, that’s at the root of everyone’s troubles.

But Full Time never resolves what happens with the transit strike, which serves only to intensify the main action. Julie’s situation may change by the end of the film but only as a refurbishment of the status quo. Despite its premise and themes, Full Time doesn’t have much to say about organized labor, or labor in general, other than that work can be really stressful. Julie’s escapist attitude bleeds into that of the film, making it little more than a competent thriller.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.

It appears that Mr. Repass wishes that “Full Time” was a different, albeit important film. One that explores capitalism, the state of organized labor and the disappearing middle class. We all wait for that one, but Full Time is simply a story of one woman’s pursuit of a place in the middle class.

Biggie G, I get your point; this film should not be criticized because it failed to make a sweeping critique of capitalism’s treatment of labor. But if Repass saw the film the same way I did, he found it oddly allergic to context. It was the director’s choice to forefront the transit strike…while avoiding the transit strikers. At times I felt it was mostly a film about a transit strike, and the human cost to other labor sectors. Bringing the two together would have added much-needed depth to this thrill ride of a movie.