Resignation to fate is the dominant affect of Gaspar Noé’s Vortex. Other films about the onset and advancement of dementia have rarely been as steadfastly bleak or as full of futile despair as this tale of an elderly couple, played by Italian horror maestro Dario Argento and French actress Françoise Lebrun, whose bond is dissolved by the disease. Never exactly afraid of formal showmanship, Noé uses split screen to represent the divide between the characters, and in the opening minutes of Vortex, the filmmaker shows us the moment that the disease comes between them by having the black bar that will separate the screen for the rest of the film slowly inch down the middle of the frame as the couple lies in bed.

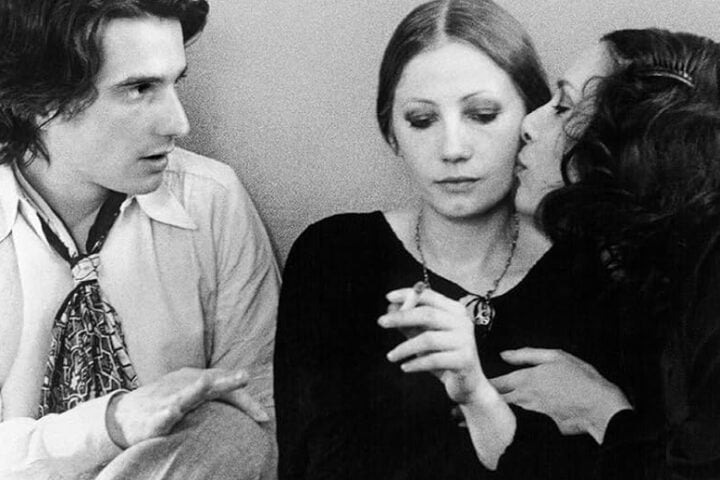

For almost the entirety of Vortex’s two-plus hours, each side of the screen captures the characters from a roving camera’s perspective. In an early scene, we watch on one side as Argento’s professional film critic begins his day of work at his typewriter, while on the other Lebrun’s retired doctor heads to a neighborhood hardware store. As the woman becomes lost in the cramped store, she’s suddenly paralyzed by confusion and fear, and the side-by-side perspectives work to underline how her dementia has disconnected her from her husband.

At other points, like when the pair are meeting with their son, Stephane (French comedian Alex Lutz), and grandson, KiKi (Kylian Dheret), the two frames give us almost continuous points of view on the same thing, but the incommensurability of the two angles becomes apparent when an arm or object stretches across the divide between the frames and appears strangely elongated or foreshortened. While we never get a shot that directly represents Lebrun’s character’s point of view, these moments enhance our sympathy with the disorientation that she feels in her less lucid moments. The way the young Kiki loudly bangs his toy cars on the kitchen table feels somehow more intense when, in one frame, we see him doing it, blithely unaware of its effect on his grandmother, and, in the other, we see her sitting just across the table but utterly alone in the shot, holding her ears and cowering.

The cameras coming together to create a kind of misaligned single frame provides a taste of the visual overload and disorientation for which Noé is usually known. But overall, Vortex finds him relatively reserved, following his characters with unflashy Steadicam shots as they move around their cluttered home, often in different directions and at cross purposes. In fact, during some of the longer stretches of the two characters not doing very much at all, you may find yourself wishing for Noé to mount some minor assault on our senses.

The film takes place in a universe indifferent and unresponsive to its characters’ hopes—in which, at one point, plans are literally flushed down the toilet. In other words, it’s set in a world emptied of the usual sentimental pieties about aging and death. At times, the pessimism here can feel as forced as the false hope offered in any melodrama—Stephane’s turn to narcotics to cope with his parents’ decline comes off as an underdeveloped means of laying the misery on thick—but there’s also profound honesty in the film’s treatment of decline and death. As the possibility not only of a happy ending, but of any real resolution, of any reconciliation with the fact of death that we might hope the characters will make, becomes remote, the film evokes that familiar but unshakeable cliché that everybody dies alone.

One respite from the loneliness of life lived in the shadow of death, perhaps, is the realm of dreams. The film has no dream sequences, but dreams are referenced repeatedly, and Argento’s character is working on a book on the relation of film and dreams. His project gives Noé a reason to sneak into Vortex the coffin scene from Carl Theodor Dreyer’s Vampyr, which plays on the main characters’ TV at one point, presumably queued up by Argento’s character for research purposes. Dreyer’s hero is loaded, frozen but conscious, into a coffin with a window built into its lid, before being lifted up by pallbearers, loaded onto a cart, and carted around town. To continue watching the world even in death—that’s probably the ultimate dream.

Across Vortex’s running time, both of its main characters seem to pass over potential insights into dealing with death that pop up in the background of their lives. The soundtrack of a long section of the film is dominated by a blaring radio report on methods of coping with death, which neither character in their respective split-screen frame seems to give much notice to, and it’s not clear that Argento’s film critic is interested in Vampyr because of what it has to say about mortality. But given what we observe in the oppressive, occasionally mundane, though still quite affecting Vortex, we’re invited to speculate as to what the thesis of Argento’s character’s book should be: that cinema is like a dream because it allows you to experience death and then return to the waking world, hopefully better prepared for the inevitable. In films and in reverie we can enter the vortex, as it were, and live to tell the tale.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.

Noe shows relation and searation of people looks like life and death. The isolation from reality is death and lack of love is some kind of mentality death.