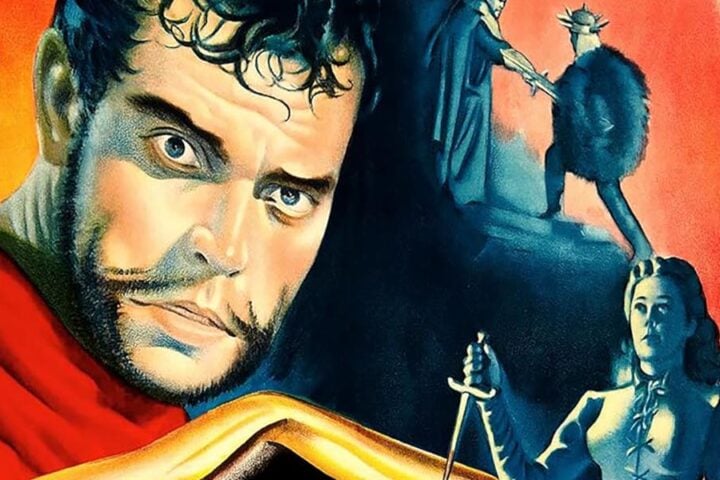

Documentarian Vittorio De Seta’s first narrative feature, Bandits of Orgosolo, builds upon several of the director’s shorts about the Sardinian region where the film is set. Featuring a cast of non-professionals, the film follows the shepherd Michele (Michele Cossu) as he and his young son, Peppeddu (Peppeddu Cuccu), end up fleeing deeper into the mountainous countryside when the father is wrongly suspected of livestock rustling and murder. With carabiners on his trail, Michele leads his child and his sheep into higher and rockier ground, and as vegetation and water become increasingly scarce, starvation rips through the flock. Eventually, and in a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy, circumstances force Michele into the sort of crimes of which he was initially innocent.

This overarching narrative recalls Vittorio De Sica’s seminal Bicycle Thieves. But where De Sica’s neorealist drama took a snapshot of postwar Italy’s shattered economic and moral torpor, De Seta’s own approach aims at ideas less tethered to a specific time or place. Moving the story from the city to the countryside casts the same basic story as a depiction of man’s elemental, and ultimately futile, struggle to both survive the vastness of nature and assert dominance over it.

Throughout, De Seta routinely arranges shots in which the characters are dwarfed by their surroundings, even when people stand in the foreground. Some shots gaze over Michele’s shoulders as he stands on outcroppings, with the vast landscape of rolling hills and dales below him making the man into little more than a dot at the bottom of the frame. Elsewhere, the camera films him from low angles to stress the rising cliff faces behind him, as if to suggest that no amount of climbing will ever result in him reaching the summit of the mountains.

Bandits of Orgosolo often feels outside of time. When we first meet Michele, he’s wearing a fur cloak that looks positively prehistoric, and even his regular dress is the sort of peasant wear that could have existed in the 19th century. (The film regularly spotlights laborious tasks like boiling drinking water or salvaging old rope that have clearly been practiced by people in this region for hundreds of years.) It’s remarkable to consider that this film was made at the same time that Italian luminaries like Federico Fellini and Michelangelo Antonioni were depicting the nation’s urban centers as hotbeds of aesthetic modernism and postwar alienation. Those directors showed an Italy overcompensating for its recent past by forging a new identity, but Bandits of Orgosolo suggests that the nation’s deeper history could still assert itself over its citizens.

Image/Sound

While there are discrepancies in image quality owing to the film’s mix of natural and stage lighting, Radiance’s presentation looks stunning overall. Barring a few instances of flicker and softness from fluctuations in sunlight, even the exteriors boast crisp detail and stable contrast that render the panoramic landscapes in painterly clarity. So much of Bandits of Orgosolo’s power stems from its depth-of-field images, and detail is so fine that you can make out faint contours in the craggy background landscapes. The mono soundtrack has all the benefits and drawbacks of classic Italian dubs: Each line of dialogue and sound effect is crystal-clear, even if the falsity of these post-sync sounds clashes with the naturalism of the film’s shooting methods.

Extras

Radiance’s disc comes with interviews with film curator Ehsan Khoshbakht, who discusses Vittorio De Seta’s unique position within postwar Italian cinema, and cinematographer Luciano Tovoli, who shares his experiences working with De Seta on several of the director’s short documentaries and the unique challenges of shooting Bandits of Orgosolo.

A booklet essay by Italian film historian Roberto Curti offers a wealth of historical information about the Sardinian region where the film was shot. Curti also meticulously analyzes De Seta’s formal methods and how they play into the narrative’s textual and subtextual threads.

Frustratingly, the North American edition of this release lacks “The Lost World,” a compilation of De Seta’s extraordinary anthropological shorts, which sit at a fulcrum point between pure ethnography and the kind of transcendental realism that Roberto Rossellini pioneered starting with his collaborations with Ingrid Bergman. Fortunately, though, both versions of this release are region-free, and the U.K. edition is easily purchasable at specialty retailers.

Overall

Bandits of Orgosolo, Vittorio De Seta’s evocative work of ethnographic fiction, looks gorgeous on Radiance’s Blu-ray, though viewers who want to see a selection of the director’s iconic documentary shorts should seek out the label’s region-free international release.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.