Martin Scorsese’s The Last Waltz approaches the concert movie as a bedrock for formal experimentation, one where every lighting choice and camera movement is carefully considered. As the Band rehearsed for their farewell show at San Francisco’s Winterland Ballroom on Thanksgiving Day, 1976, the filmmaker aggressively storyboarded ideas for each song that the group practiced, envisioning how to adjust the stage lighting to reflect mood and timing cuts and movement around each composition. Scorsese’s unorthodox approach is evident from the start, when the first song that we see the Band play in the film is the last performance of the evening, a short and giddy playthrough of “Don’t Do It.”

The rest of The Last Waltz jumps around the setlist from the Band’s show, which took the form of a revue that stretched nearly 10 hours from a pre-concert dinner and ballroom dance to the final number that opens the documentary. The members of the Band, who began their working relationship as session men and maintained associations with the various acts that they supported even after striking out on their own, surround themselves with all-star guests like Neil Young and Bob Dylan, lending an opulence to a style of music that otherwise stressed the humble folk and blues roots of rock ‘n’ roll. Elaborate camera movements, staged by an assembly of all-star cinematographers including Vilmos Zsigmond and Michael Chapman, highlight the sheer grandeur of the Band flaunting their musical connections.

But the real payoff of Scorsese’s obsessive pre-planning is the elegance with which The Last Waltz captures the interactions between the Band’s members and their guests, as well as each musician’s flourishes and interplay with one another. When Levon Helm takes lead vocals on songs like “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” for example, the camera always frames his face perfectly encased in his drum equipment as he manages to keep time even as he throws his entire body into singing certain verses. And the film never falls into the habit of cutting on nearly every beat like so many concert movies, instead often gliding between instruments in a single take as if tracing the cues that the band members are sending to one another.

The guests, too, are filmed in ways that are appropriate to their style and aura. Joni Mitchell remains bathed in light as she strums out her jazzy “Coyote,” while Ronnie Hawkins’s bawdy energy is matched by darker tones that suddenly give the Winterland Ballroom’s stage a barroom look that’s a perfect match for his bluesy drawl. The show-stopping performance of “The Weight” featuring the Staples Singers is so attuned to the glee on the Band members’ faces as Mavis Staples takes a solo verse that you almost don’t notice that this didn’t even occur during the actual show but in subsequent soundstage reshoots.

For all the intricacy of Scorsese’s direction, some of The Last Waltz’s most memorable moments are the result of mistakes. In several of the between-song interview segments, Scorsese puckishly includes jarring jump cuts to the Band’s members, most especially Robbie Robertson, responding to a question and then asking if they can change their answer. And the hypnotic single take in which blues legend Muddy Waters stomps out his classic “Mannish Boy” wasn’t a conscious choice to hold on his face as he contorts each vibrato hum but the result of every camera but one being down for reloading. As with the Band’s finely oiled but deliberately ramshackle love of primitive rock, these flaws only enhance the majesty of the film, reflecting small flashes of human error that underscore the harmony of everything else.

Image/Sound

Criterion’s transfer beautifully renders minute details like the texture of clothing, the sweat glistening on the performers’ faces, and the subtle overlays of the stage lighting. The darkened shots of the crowd are so free of crush that you can make out people’s faces. The transfer is free of blemishes of any kind and looks significantly sharper and more film-like than prior video release of The Last Waltz. Three audio tracks are included: a 5.1 surround remix and 2.0 stereo track prepared in 2001, as well as the original mono. All three are clear and well-balanced, revealing subtle details within the intensity of the music. The surround sound in particular is so enveloping that you may feel as if you’re actually inside the venue.

Extras

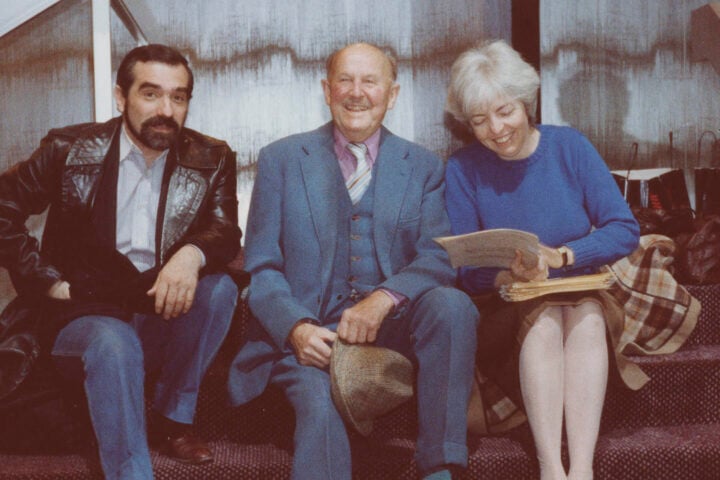

Two archival commentary tracks are included. One features Martin Scorsese and Band guitarist Robbie Robertson, who were recorded separately, and both share their unique perspective on The Last Waltz and the concert itself. The other track features a slew of figures ranging from members of the Band to guests like Mavis Staples to producers and even rock critic Greil Marcus. Both tracks offer a wealth of information, from Scorsese’s precise technical breakdown of shots to Ronnie Hawkins relating his relationship with the Band.

Across a series of new and archival interviews, Scorsese delves into his interest in the project and how he wanted to make a music documentary that was in line with his narrative features of the time. A 20-minute retrospective documentary from 2002 covers a lot of the same ground as Scorsese and Robertson look back on the film and their subsequent working relationship.

The most fun extra is footage from one of the show’s jam sessions where a number of musical guests join the Band for an improvised number. There’s also a booklet essay by music critic Amanda Petrusich, who unpacks the Band’s career, the concert and the film with an expert grasp of the context of mid-’70s rock and contemporary rock docs.

Overall

Martin Scorsese’s radical advancement of the concert documentary receives a superlative transfer that reaffirms the film as one of the director’s great aesthetic achievements.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.