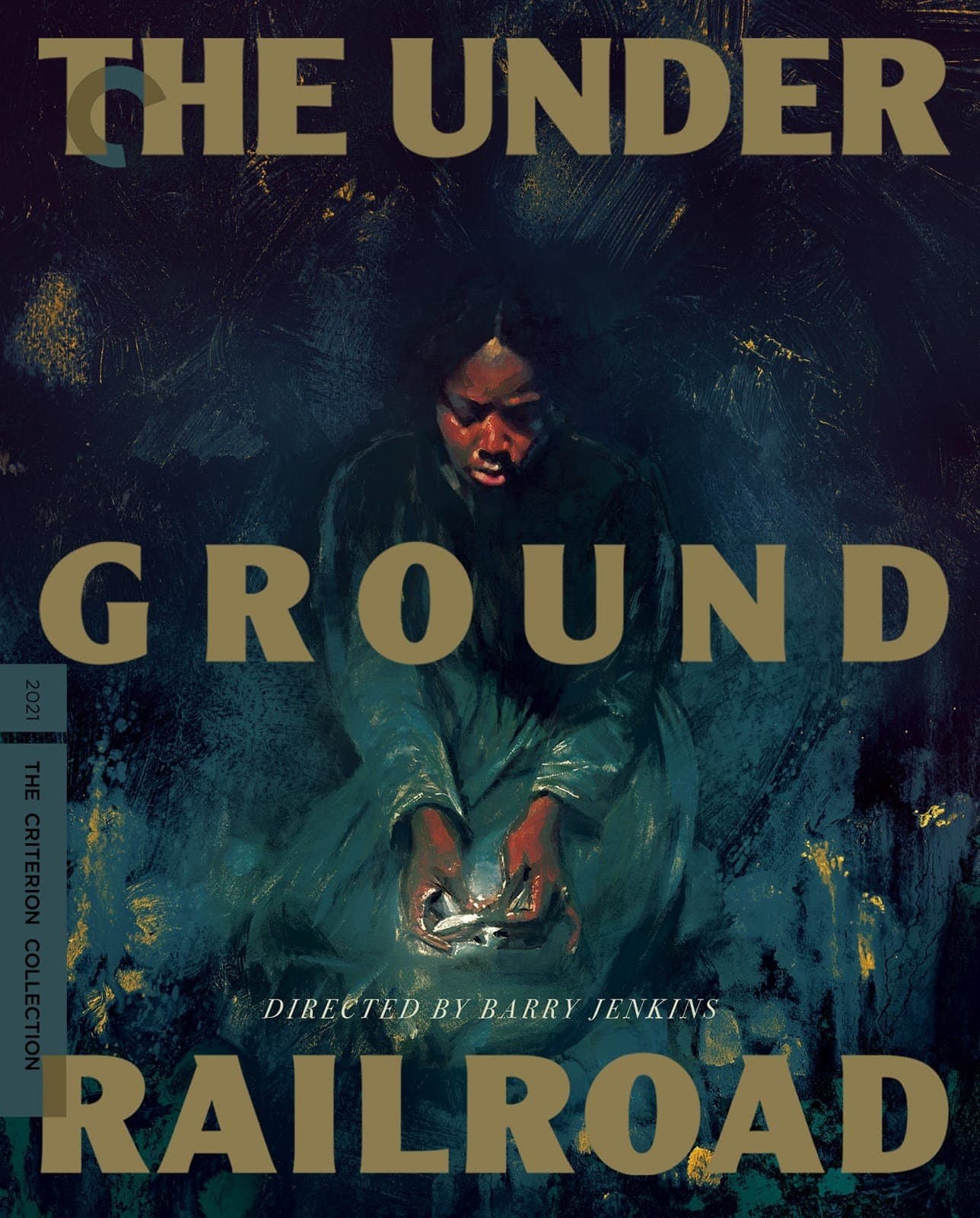

“A plantation was a plantation,” Colson Whitehead wrote in his 2016 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Underground Railroad. “One might think one’s misfortunes distinct, but the true horror lay in their universality.” It’s that sense of infinite trauma—spreading across the United States, backward and forward throughout history, and deep into the souls of the enslaved—that comes across most palpably in the 10-part adaptation of the book, which is unsparingly and expansively directed by Barry Jenkins.

“A plantation was a plantation,” Colson Whitehead wrote in his 2016 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Underground Railroad. “One might think one’s misfortunes distinct, but the true horror lay in their universality.” It’s that sense of infinite trauma—spreading across the United States, backward and forward throughout history, and deep into the souls of the enslaved—that comes across most palpably in the 10-part adaptation of the book, which is unsparingly and expansively directed by Barry Jenkins.

On her flight from the Georgia plantation that her mother vanished from years earlier, Cora Randall (Thuso Mbedu) is asked to share the story of her pain. In Whitehead’s version of history, the railroad isn’t a metaphor but a real underground transportation system with stationmasters and conductors and locomotives, some with curtained windows and wine aboard. Every stop represents a new hope and space for testimony. In each state that Cora disembarks, she reckons with her history, giving voice to where she’s been while facing slavery’s long shadow twisted into new forms: the smiling eugenicists glad to teach her how to read, or the religious fanatic (Lily Rabe) eager to save the soul of the woman trapped in her care while neighbors execute a Black woman in the public square.

Even when Cora finds refuge (and love) on a Black-owned farmstead, a community brimming with care and art and comfort, her emotional and physical scars resurface. As a railroad conductor warns her and her companion, Caesar (Aaron Pierre), her journey North will show her “the true face of America,” and Cora sees the specter of what she left behind again and again. This is a world, after all, where Black achievement, exemplified by the railroad that carries Cora from Georgia to Indiana, can only thrive when hidden beneath the earth.

Horror inconspicuously seeps throughout the pages of Whitehead’s novel, and the most shocking brutalities come and go so softly, sometimes in the space of half a sentence. Not so here: The opening episode is a graphic montage of assault and destruction of Black bodies, a terrorscape of violence that feels present in every scene that follows. It doesn’t matter where Cora goes or who goes with her; running away is an option, but escape—escape to safety, escape from memory, escape from the need to keep escaping—is an impossibility.

It’s in the rare moments of joy that Cora experiences that Mbedu’s performance is most meticulous. When Cora smiles, relaxes, even giggles, she transforms, but there’s a shuddering sadness in her eyes that never quite dissipates. And because we’ve seen what she sees, we sense the searing undercurrent of her history and can understand the meaning of her glance: She’s caught in the balance between the promise of a future at peace and the certainty that the past will not leave her alone. In Jenkins’s series, trauma becomes tangible.

It’s harder for the viewer to keep track of Cora’s inner life when she’s most in danger, which is much of the time. Whitehead fills the novel with visits inside his character’s thoughts, especially Cora’s, fleshing out identities beyond the circumstances of terror with crisp precision. But Jenkins, rather than trying to filmically capture that sense of dense perspectives coming into focus, leans in the opposite direction, favoring an abstract mode of storytelling with blurry, lingering shots, prolonged wide shots of tableaux in the distance that make identifying characters impossible, and slow moments of zooming-in on details that don’t necessarily reveal their meaning. Of all the music cues, it seems right that the quintessentially impressionistic “Clair de Lune” should be playing during one such disorienting reverie.

Jenkins frequently frames his characters in blinding light, the sun burning through the shot, obscuring the actors, rather than illuminating them. But that kind of light draws attention to itself rather than to what—or who—is lit: Jenkins’s storytelling, for all its surprising boldness (like the back-to-back episodes “Fanny Briggs” and “Indiana Autumn” that run 19 and then 70 minutes, respectively) and the stunning geography the camera captures, sometimes acts like that blinding light, pulling focus toward itself instead of the characters.

This adaptation also has an uninspiring investment in Ridgeway (Joel Edgerton), the slavecatcher who failed to find Cora’s mother, Mabel (Sheila Atim), all those years ago, leaving him angrily obsessed with Cora’s recapture. While the novel glances for a few pages on Ridgeway’s youth, Jenkins grants this backstory an entire languorous episode that seems to try to humanize the slavecatcher, or, at least, probe the origins of his inhumanity.

But the adult Ridgeway, played by Edgerton with a steely torpor, doesn’t seem to merit this attention. “So Arnold Ridgeway is human after all,” Cora says, unimpressed by one of her captor’s long-winded monologues about society and their proper places in it. “So here I thought you just some demon who murders folk in cold blood.” Studying Ridgeway, much like scrolling through the Twitter feed of a vocal white supremacist, doesn’t yield much unexpected nuance, and The Underground Railroad, in granting Ridgeway the empathy that he’s unable to show to others, only reinforces the futility of investigating the crudest evil.

Jenkins, though, has assembled a cast of actors who, mostly confined to one or two episodes, bring a sharp specificity even to the series’s hazier depictions of each character’s relationship to liberation. Calvin Leon Smith desperately animates Jasper, captured by Ridgeway alongside Cora, as a man who believes he can find freedom only by ceasing to fight for it. Amber Gray and Peter De Jersey deliver some of the series’s most impassioned speeches as the gregarious founders of a Black community that they’re willing to defend with their lives. And as Royal, who courts Cora in the final few episodes, William Jackson Harper movingly conveys the attempts of a man born into freedom to fully understand the suffering of the woman he loves.

The Underground Railroad’s most haunting performance, though, belongs to Chase Dillon as Homer, an emancipated child who serves as Ridgeway’s loyal, even loving, companion, choosing to manacle himself to the slavecatcher’s wagon every night with his own key and chains. Homer’s inscrutable fear of freedom is at the root of the series’s raw depiction of slavery’s scorching of the spirit. In the opening episode, as Caesar tries to convince Cora to leave with him, he tells her, “I’m not supposed to be here” and she responds with a broken “But I am.” Cora’s freedom from that belief, her ultimate surety in the birthright of her humanity, is the only untainted victory that The Underground Railroad will allow.

Image/Sound

While the fundamental strengths of the cinematography shone through on Amazon, streaming compression frequently compromised moments of low-light photography or heightened contrast with crushing artifacts and loss of detail. Though the Criterion Collection only offers a 1080p Blu-ray of The Underground Railroad, at times it outshines the ostensibly 4K stream on which it was originally broadcast. Detail is consistently razor-sharp and color balance is attuned to the subtle variations in the African-American cast’s respective skin tones while showing off the full range of greens, browns, and cool blues of the show’s color palette. Dark interior and nighttime location shots are free of crush and show deep black levels, and the occasional gas lamp looks incandescent in its intensity against natural lighting or the soft glow of candlelight. The Dolby Atmos soundtrack is enveloping and immersive, ably blending dialogue, background chatter, and music across all channels while maintaining clarity of each element.

Extras

Criterion’s set comes with commentary tracks by Barry Jenkins for each episode, as well as an introduction in which he notes that he recorded them in the order that the episodes were shot, not in the order in which the episodes aired. Joined by cinematographer James Laxton and editor Joi McMillon on select chapters, Jenkins offers copious details on his approach to adapting the Colson Whitehead novel, his collaborative spirit with the actors, and the careful balancing act of showing the horrors of the era without exploiting them.

But perhaps the single most consistently insightful aspect of his commentaries is Jenkins’s material focus on how hard he and his crew worked to stay within budget for a series that lacked the usual avenues of cost amortization thanks to its period detail and constant changes in location. Hearing the director break down in detail all the shrewd ways in which The Underground Railroad was structured around making the most out of limited resources is a fascinating reminder that great art is often born out of limitations that test artists’ creativity.

Elsewhere, there are deleted scenes from various episodes; a featurette on the design of the railroad station sets; a graphic-novel adaptation of an episode cut for time and budget in pre-production; teaser trailers made by Jenkins; and “The Gaze,” a short film by Jenkins comprising shots of cast members in costume filmed silently staring at the camera. The film slowly attains power through repetition, what might have initially just been test footage becoming a conscious engagement with the inevitable distance of a fictionalized period portrait and the paradoxical connection it can nonetheless offer to the real past. There’s also a booklet essay by critic Angelica Jade Bastién that details the ways that both Colson Whitehead’s novel and the adaptation shake up clichés of slavery dramatizations.

Overall

Barry Jenkins’s remarkable TV adaptation of Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer-winning novel receives a gorgeous and generously loaded box set from Criterion.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.