In one scene early in Todd Haynes’s new film, May December, Joe’s (Charles Melton) face flickers with the grey-blue light of the TV screen playing a commercial for face wash. The commercial stars Elizabeth (Natalie Portman), the TV star who will be playing his wife, Gracie (Julianne Moore), in an upcoming film and who will be visiting their home to do research for the role. The brief shot of Elizabeth’s face, sparkling with water and freshness and something like “realness,” loops on itself over and over again, while Joe’s eyes glaze over.

Later in the film, days into her research into Joe and Gracie’s lives, a lurid scene of an adult woman seducing a 13-year-old pet store employee plays on the television set in Elizabeth’s hotel room, a black bar on the screen boldly stating “Do Not Replicate.” It signals at once a trashiness and a cultural obsession with toggling between the sensational and the approximation of the truth. Both scenes, flickering on a screen, are as much smoke as they are mirror.

With his latest, Haynes has given his audience the chance to suck on a radioactive lollipop, at once pleasurable and shocking, delicious and diabolical. Haynes is one of the few filmmakers whose work defined the New Queer Cinema grads who managed to go mainstream, but without compromising his ideas, intellect, or formal rigor. May December is an age-gap romance that’s also about swapping personas, performance and performativity, spectatorship and surveillance, innocence lost, the uncanny and the authentic, and the unrealness of the real. Yet, for as intellectually and thematically dense as May December is electrifying and exciting, infused with a poisonous sense of humor, a wickedly prickly cynicism, and a tender, broken heart.

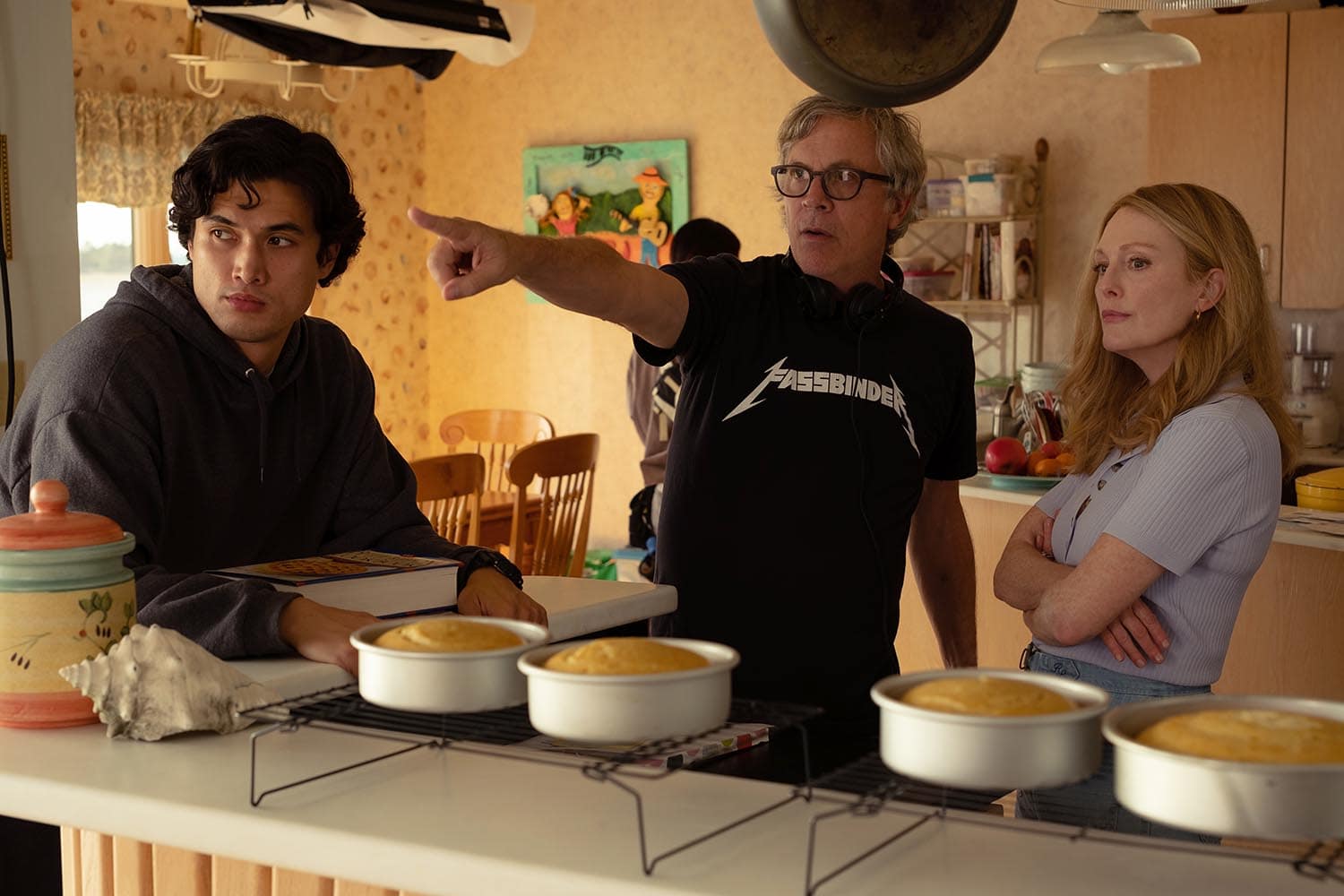

I spoke with Haynes ahead of him receiving the Queer Visionary Award at this year’s NewFest. We discussed the repetitions that abound in May December, the use of Michel LeGrand’s score from The Go-Between in the film, the search for emotional truth, role play, more.

You had a retrospective at the Pompidou and you’re having a retro at the Museum of the Moving Image. How was the former and how’s the latter going?

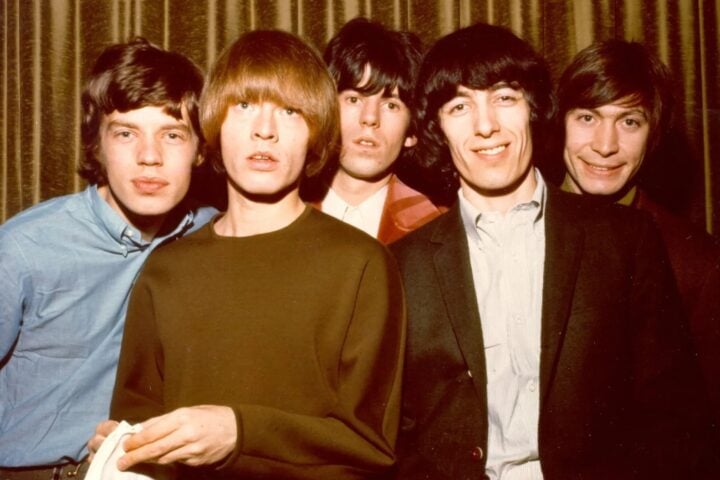

Oh, this year has been really crazy. When I did my opening remarks at the Pompidou I just said it’s sort of like dying and having your life pass before your eyes but in a really good way. I told an anecdote about Donald Cammell, who was the co-director of the movie Performance with Nicolas Roeg, and the way he decided when he wanted to kill himself. He wanted to stay as conscious for his own death as possible up to the last second, so he studied how to shoot himself in the head to do so. And as it turned out, how he shot himself in the head was the way James Fox shoots Mick Jagger in the head at the end of Performance, and so his last words refer directly to his own movie. So I’m living and dying my own life as best I can.

There’s a part in May December where Joe is smoking pot with his son, Charlie, on the roof and he says that it would be funny if he had to take his own X-ray. Do you ever think about having to examine yourself in the same way?

I don’t want to examine myself that much.

But you’re a Freud fan!

I am a Freud fan. I should have gone through analysis at some point. But it’s more that I love the way the narratives that he created for the way we look at human nature and the way we all function and the way we navigate our unconscious lives with our conscious lives and how much being in some state of despair is normal. And not solvable, not fixable.

What part of your unconscious are you bringing to May December?

Fassbinder once said, “Every decent director has only one subject, and finally only makes the same film over and over again.” And somebody else said that the one thing that makes you utterly unique as an artist or filmmaker is the thing you don’t see. Hitchcock didn’t think he was making the same film over and over again. He was interested in all the specifics that were compelling him in each new film—the different locations, the different styles, that different stories, the different camera moves that he was going to work into his movies. But as he was doing that, residually he ended up creating an entire coherent body of work that changed the medium forever. And maybe that’s his unconscious, the thing that he didn’t see, that is him. And the conscious is the thing that you’re preoccupied with each time, you know?

Are you afraid to look at what you cannot see?

I watched a few of my films at the Pompidou because I hadn’t seen them in a long time, and I was going to be talking about them. I’m Not There was, I think, my favorite film that I made. But Carol, I forgot the storyline. And I was watching it, like, “Oh, my God, I hope they get to stay together.” I had forgotten what happens after she gets that letter. It was like I was watching it like a spectator in the room, you know? So, I don’t know. These things come out of you, and they go out into the world, and they kind of are their own. And you can reacquaint. It’s a cliché, but they’re like kids that you have that have their own life. And I certainly know this with kids as they keep growing and changing. But you have an encounter with one of your kids. And you’re like, wow, I didn’t even think I knew you. Until today. Because you’re only who you are at that moment. And then you might be somebody else. As you keep growing and changing.

And so much of your work is concerned with the malleability of identity, performance, spectatorship. May December may be your most explicitly meta-cinematic film, where you have like scenes on a set. Were you thinking about you yourself as an object of spectatorship during that process at all?

No, not so much. I’m interested and I love the multiples that the film circulates in, from the very basic premise of the scandal happening some 20 years ago, to the gulf between the past and the present, to the entrance of an actor who’s going to make a movie about the past who’s coming in and is a mirror of the woman who was the epicenter of the scandal, because she’s now the same age that the woman was when the scandal occurred. In the process of that is the filmmaking, as you’re making multiple takes, you’re doing it over and over again, you’re revisiting the same idea and trying to get it down and you’re breaking down the shots. And it’s a kind of severing and turning it into all of these separate components and then putting it all back together again, as if it never was separated. And trying to hide the fact that it was in multiples in this movie kind of exposes all the multiples and ends in a series of a circular circularity. I’m trying to achieve something that you never will achieve, which is truth.

The two main characters are also trying to achieve that too.

I don’t know that either of them are seeking any idea of truth that isn’t completely and totally suspect, and completely received by culture, right? Particularly Elizabeth, who’s embodying and concealing privilege and power [that she has as an actress]. Whereas Gracie, I think, cannot confront truth. And what the film turns into is a duel of powers around notions of who’s stronger: the one seeking the truth or the one denying it. And in many ways, they both are in all kinds of states of denial, but I think Gracie ultimately wins the hand game.

What were your approaches as far as creating a visual grammar for the Lifetime movie, and then creating an atmosphere for the meta-film at the very end, and having them be in dialogue with each other?

We were playing with all these versions and editions of various forms of representation and narrative. We are enlisted in a kind of hierarchizing of them: which is true, which is better or worse, which is trashy or classier. But that’s kind of an evasion, that process of ranking. And I think the film ultimately also reveals that the sort of ways that these different films are all part of the same fabric of sort of recycling of ideas and, you know, the thing that feels the most contaminated by that process is Joe. And so the film needs a counterpoint to the sort of cynicism of its humor and its representation of all these layers of repetition, and he’s that.

You use the music from The Go-Between, which is also a movie about the corruption of innocence. Were you discussing with the cast, like, the places that you wanted to put the music in? Because I know that you would use it in pre-production and then during the editing process.

It was through the entire shoot. We played music every day, scene by scene where music [would play in the movie]. I laid in the queues wherever I thought music would end up playing. This is nothing that you normally do, but I wanted to. I just wanted to just see what it’d be like to lay in the different cues from the Michelle LeGrand score into the script. This music is wild. It breaks every rule of movie music that I’ve ever known. We just played the music that I’d laid into the script, in every place that it appeared in the film. And if there was dialogue, we just would turn the music down, play the dialogue and record the dialogue, and then turn it back up. So the music was informing everything. The DNA of this film is conjoined with this music.

I’ve been listening to it on repeat on my Spotify after having seen it. It really does sort of shake you away. And it’s also romantic and scary and tragic. You said that the shoot was like 23 days. Why say yes to production that’s 23 days?

It was the only way. We only had so much money. It wasn’t a super long script, and had a plan to do it economically. The conception of the movie was that [most] scenes were single shots. It wasn’t as scary as I thought it would normally sound, when you were trying to get more coverage per scene than we did. What’s scary is that there was no alternative. We shot it one way. And that was it. So there was no way to change it once I’d committed to this way of shooting.

And what do you mean by “this way of shooting”?

By doing whole scenes in a single shot. If the shot didn’t work, you’d either just cut out of it sooner or cut the scene out. There was no B plan. So it was just sink or swim. And so I was just, like, “Okay, let’s just go for it.” And so we all did and joined hands. I brought everybody into this idea—this process of playing the music, and they also looked at my image books. Leading up to the shoot, April Napier, my costume designer, was like, “Todd, was there a film list?” And I was like, “Well, yeah, of course, April. There’s always movies I’m watching. Most of them are in the image book, but there’s some other ones.” And she was like, “I want to watch!” Listen, I was like, “I didn’t want to give it to people like homework.” And she was like, “No, no. I want to watch all the movies.” So it was like everybody was watching all the movies.

I love homework. What other movies did you have in the image book?

Bergman’s Autumn Sonata and Winter Light, Allen’s Manhattan, Nichols’s The Graduate, Schlesinger’s Sunday Bloody Sunday, Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt.

One of my favorite scenes is when Elizabeth is giving the talk back at the school. It’s an incredible example of someone who’s performing when an audience doesn’t think they are. Why did you choose to shoot Portman from above her shoulder?

I just wanted a different angle on her. And we never have a shot from, like, the front of the audience’s view of her. It’s always from the side. I just wanted this oblique high of the shoulder angle. I didn’t know how we would use it. But two things on that scene. One is that Natalie was so amazing, because when we did the reaction shots of the kids, she went off script. And she just got more obscene. She just went off the charts. First, Chris Blauvelt, my director of photography, started to crack up, but he wasn’t making any sound. And then I started to crack up. And you can hear me cracking up on the shot and the student and the kids were amazing. They didn’t break. They stay completely in character. But the other thing about that scene is, as much as the scene is a tour de force for Natalie, the scene needs Mary [Elizabeth Yu’s character, Joe and Gracie’s daughter]. She’s the anchor of the object of that scene. And she blew me away.

What was it like filming these young people sort of becoming aware that there’s always a level facsimile to when we’re sort of negotiating everyday life?

These young people are unlike those in Sirk movies. They’re the only ones who really see and understand everything that’s going on, every reason why they need to leave that house and move on with their lives. And they’re going to be fine. The casting of Charles Melton took me in a different direction than other actors who read for Joe, who were more what I pictured when I read the script, and Charles made me see the character in a way that was just so deep and surprising. But it was the same with Gabriel Chung, who was different than I pictured Charlie. And he also had never acted before in his life. And, again, it was like it was the mirror of Joe.

Also fascinating about the film is the notion that all relationships are sort of parental. Everyone’s surveilling everyone else and sort of teaching them how to be in a very parental manner. Whether it’s Gracie and Joe or Joe and his kids.

They keep switching roles. All the roles keep inverting.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.