Yorgos Lanthimos’s films are prone to hitting audiences with a pit-of-the-stomach feeling, from the pyrrhic victory that closes and overwhelms The Favourite to the unbearable uncertainty of whether someone will disfigure themselves for the sake of love that lodges The Lobster in the heart like a knife. No matter how hard Lanthimos’s characters fight for agency or freedom or power or love, life is still savage and cruel and unforgiving.

But in Poor Things, as unpleasant as life can be, especially for a woman, there’s still hope in the sheer and bizarre splendor of it all. The film is adapted by Tony McNamara from Alasdair Gray’s novel of the same name, which is inspired by Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and its interrogation of Victorian repression and hunger for the power of God. And for better and worse, Lanthimos’s acute awareness of that inspiration imbues the film with an unmistakable irony. His penchant for absurdity is unmistakable, but Poor Things is filled with the kind of sunshine and humanist fabling that at times feels discordant with his natural timbre and perspective.

The creature at this film’s center, Bella Baxter (Emma Stone), is a young woman who’s brought back to life by Dr. Goodwin Baxter (a perfectly Karloffian Willem Dafoe), whom she calls God. Bella is defined by her weird baby talk (after all, she now possesses the brain of a child), voracious libido, and boundless curiosity about the world. She mixes that baby talk with complex terminology (a character points out that Bella doesn’t know what a banana is but that she also uses the word “empirically”), is afraid of nothing, and uses her tongue and stoicism as weapons. She’s more self-possessed, particularly as a woman, than most people in “polite society” would ever dare to be, which relegates her to the margins as a kind of monster.

Lanthimos is a skilled director of blunt strangeness and surreality, and the way those qualities collide with fundamentally embarrassing qualities of human nature and how they’re manipulated by others has become a core component of his filmography. And if he weren’t, it would be a lot easier to dismiss Poor Things as an accessibly weird romp through a Victorian-steampunk world defined by its garish colors and topsy-turvy architecture, and which is sometimes presented in black and white and through a fish-eye lens.

The film’s warmth is partly a result of it feeling like a homecoming for Lanthimos. Like his breakthrough Dogtooth, Poor Things is about someone who must contend with the real world’s contradictions. In both, consciousness and free will must bend to social edicts, and language is duplicitous and weaponized. But while Dogtooth’s view of humanity’s capacity for cruelty is an acrid one, Poor Things suggests that Lanthimos continues to soften over time.

Poor Things abounds in spit takes, incongruous expletive-shouting, and slapstick—comic bits that recall Monty Python as much as Lanthimos’s earlier work. Jokes pack and pad almost every scene: This is a film that features a chicken with a dog’s head, sees Dr. Goodwin burping shiny moss-green bubbles, and gets considerable mileage out of Bella’s sledgehammer directness (“Why keep it in my mouth if revolting?” she says, before spitting out food at dinner). Lanthimos’s pristinely dark humor may be softening, but he still demonstrates an interesting range when mining things for laughs here, be it visual gags, crassness, or line readings.

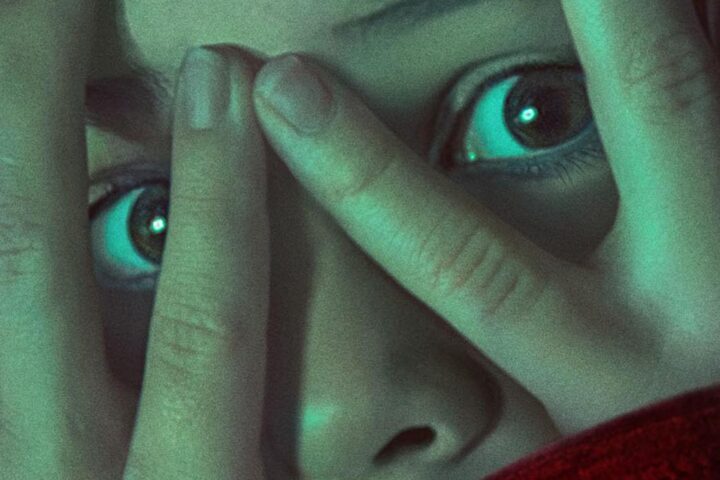

As imaginative as the film’s comedy can be, though, its greatest asset is Stone’s ability to situate Bella first as jester, then as the emotional foundation upon which the whole of Poor Things is built. Stone’s acuity in portraying a woman coming to grips with the overwhelming experience of becoming self-aware and what to do next is entrancing. We read on her face Bella’s ability to negotiate more and more complex and intricate emotions, ideas, and feelings. Stone grounds the film with her smirks, eye-rolls, ecstatic cries, and sullen frowns. While Lanthimos plays around within his Victorian world, Stone does the heavy lifting of adding flesh and blood to Bella.

The film frames Bella as a resilient Job-like character as she journeys from London to Lisbon to Paris, with the “real world” trying to dim her enthusiasm for her growing understanding of everything around her. Jarrod Carmichael and Fassbinder alumna Hanna Schygulla make appearances as cruisemates arguing for whether humanity is just plain evil and cruel or not, as Bella’s consciousness and capacity for feeling becomes more complex and intricate. Carmichael’s Harry Astley shows her a slum during one of the cruise’s port stops and she’s brought to tears, unsure of what to do and how she can fix society’s ills.

But while Bella’s perspective about life is supposed to be growing deeper, more contradictory, the parts that are supposed to most complicate her point of view lack the gravity and immediacy of the shock of learning that people can be bad and that bad things happen all the time without reason. Instead, there’s a wink, even when her adventure-time beau, a lecherous lawyer named Duncan Wedderburn (Mark Ruffalo), tries to manipulate and emotionally abuse her. Bella’s simple refusal to acknowledge his attempt at wielding power over her carries the tough double duty of showing her strength and revealing the lengths that men will go to in order to possess women, but Ruffalo’s buffoon isn’t scary so much as he is more babyish than Bella.

A majority of the savagery that’s supposed to contextualize life in totality for Bella is often framed as jokey throughout Poor Things, and such real and existential ferocity never broaches the unsavory or uncomfortable close enough to find the delicate balance between the darkly funny and the truly horrifying. Even when Swiney (Kathryn Hunter), the madame of a Paris brothel where Bella begins to work at, bites our heroine’s earlobes, the real tension that exists between the two is downplayed. Is it too terrifying even for Lanthimos and McNamara to fathom the unpleasantness of the relationship between a predatory boss and a compliant employee?

Certainly, the droll, deadpan acceptance of terrible things happening to someone has stung more and gotten deeper beneath the skin in Lanthimos’s previous work. Punishments like John C. Reilly’s Lisping Man having his hand forced into a toaster oven in The Lobster for breaking a special hotel’s rules by masturbating are awful not only because they are absurd, but also because they’re delivered with such a straight face. By contrast, everyone in Poor Things is making faces. They look agog or lusty, deranged or skeptical, sometimes all at once.

For Stone, that’s advantageous, as Bella’s maturation and contention with the paradoxical nature of the human spirit is totally legible across her expressions. But for everyone else, it takes the snap out of a story that’s fundamentally about whether or not someone can reconcile with the extremes that almost everyone has to live with. The expressionlessness of Lanthimos’s characters, or their ability to make the subtlest of looks, in his earlier work is what gives them their emotional power: simply having to withstand it all, without a flinch.

Poor Things, still, is an adventurous and imaginative film. It has an ingenuity about its exploration of the tension between the capacity for good and bad that people have and how that gets codified within organized societies. It proves that Lanthimos is up to flexing his dictatorial muscles as far as his approach to what period films look like and how they interpret the past, particularly in relation to social and political norms from history.

But given that Poor Things relies nearly entirely on comedy with little real pathos, it makes all of the “furious jumping” (read: sex and masturbation) that Bella likes to indulge in and the film’s cutesy humanist riffing feel a little, if not insincere, then at least hard to fully believe. If the darkest parts of Lanthimos’s film are almost always undermined by a sense that we’re supposed to laugh, how are its more humane and optimistic moments supposed to resonate? There are few scenes of real seriousness, where the stakes for Bella feel like they truly matter. Without the sharp, unforgiving contrast of Bella having to experience the depravity and cruelty that truly impacts others, never mind herself, it makes the film’s sense of humanism, its belief that people are ultimately going to choose goodness, feel somewhat underboiled.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.