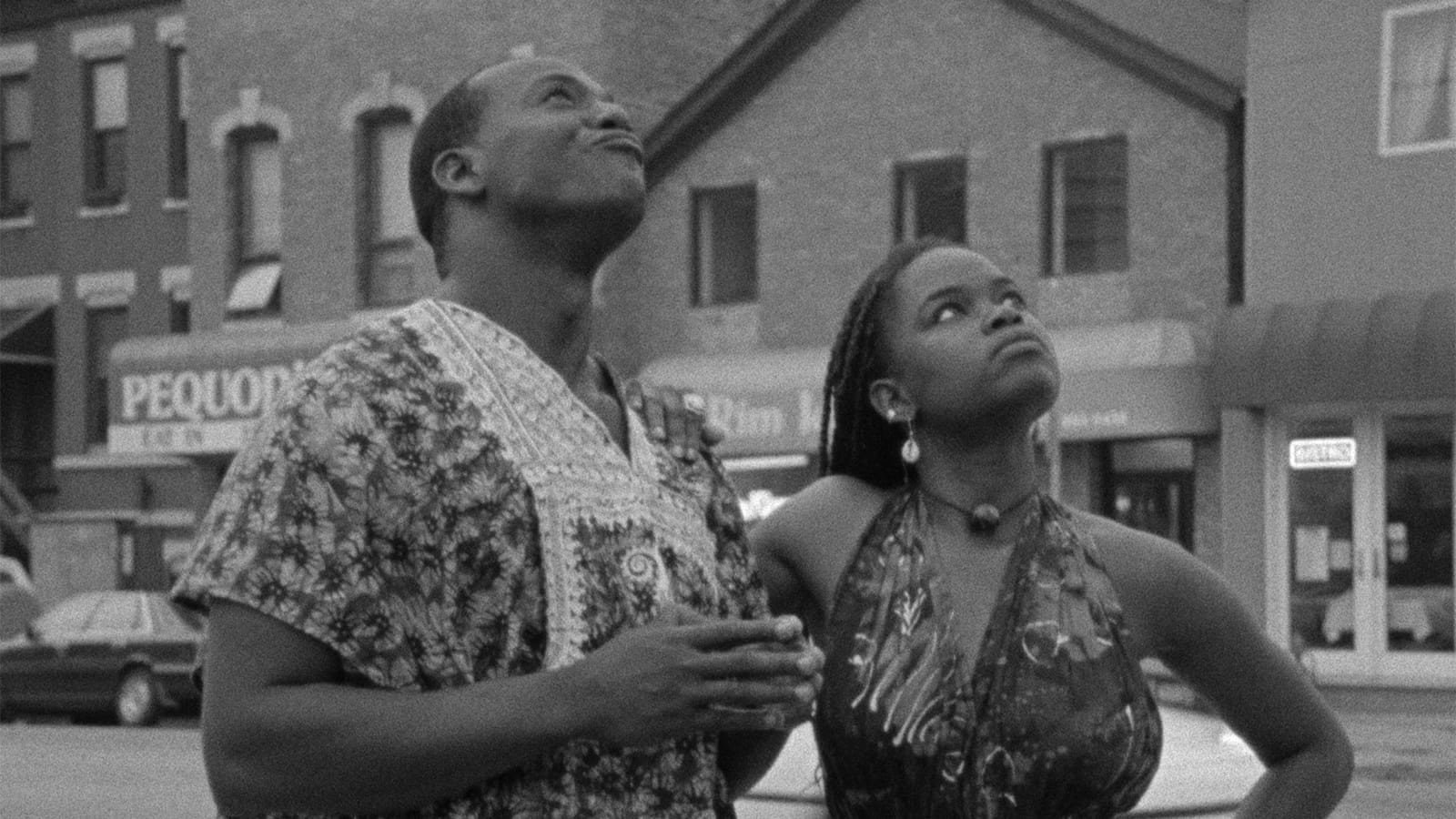

Zeinabu irene Davis’s 1999 film Compensation transcends its modest methods, leaping between genres and time periods with the aid of little more than some costume changes, a bevy of archival photographs, and techniques informed as much by silent film as by the informal, relaxed indies of its time. Following and spiritually linking the fates of two separate couples (both played by John Earl Jelks and Michelle A. Banks) in 1910 and 1990 Chicago, Compensation, written by David and her husband Marc Arthur Chéry, sketches an image of Black history at once ever-shifting and frustratingly locked into cycles of pain and perseverance.

At first, panning shots over still photographs of 1900s life in Chicago’s Black neighborhoods and figures like poet Charles Laurence Dunbar (whose 1905 poem lends the film its title) make Compensation seem like the kind of PBS documentaries that proliferated in the wake of Ken Burns’s The Civil War. The images are accompanied by intertitles that mark moments in Black cultural history, from the mass migration to northern states to the artistic contributions of authors like W.E.B. DuBois or composer Scott Joplin. In a manner redolent of some of Burns’s techniques, Davis lays a soundscape of early 20th-century city life over these images, such as setting photos of factory labor to the sounds of machinery grinding away. It’s a small touch that lends an illusion of three-dimensionality to what could have been a simple montage.

Each of Compensation’s timelines is anchored by Banks playing a deaf woman who finds herself in an unlikely relationship with a hearing man with no knowledge of ASL. In the 1910 storyline, Malindy, a teacher at a local school for deaf Black children, has a chance encounter on a Lake Michigan beach with fisherman Arthur (Jelks), who attempts to sell her some wares. When she attempts to communicate that she’s deaf via note, the man admits that he cannot read.

Despite this seemingly unbridgeable communication gap, the two hit it off and begin to see each other. Malindy simultaneously teaches Arthur literacy and basic sign language while letting down the understandable guard that she’s erected over the years against hearing people. Or, as one intertitle puts it succinctly and poetically, “Arthur learns to read. Malindy learns to love.”

This romance contrasts with the similar one begun by graphic artist Malaika and librarian Nico in 1990 on the same stretch of lakeshore. Here, again, the initial interaction between the deaf woman and the hearing man is awkward, which doesn’t impede a connection from forming nor the hearing man from dedicating himself to learning to sign in order to get closer to the woman.

Compensation bridges the gaps between these time-dilated romances via a number of parallels, from the use of bass-heavy music (Arthur’s guitar in 1910, Chicago house music in 1990) to the skepticism expressed by Malindy and Malaika’s friends toward the risks of dating a hearing individual. Most prominently, both plots concern the specter of epidemic diseases, namely tuberculosis in the past timeline and AIDS in the contemporary one. In both cases, illness not only drives an additional wedge between two people but also subtly highlights the increased vulnerability to viral outbreaks among marginalized and underserved communities.

As the twin dramas play out across Compensation’s runtime, Davis fills the film with small aesthetic touches that deepen the contrasts between the two time periods while also subtly linking them in a continuum. The intertitles are a constant delight, not only for the manner in which fonts shift according to the penmanship or articulation of people speaking and writing letters but also for the distinct borders around the intertitles depending on the time period. The intertitles for the 1910 segments are bounded by elegant white lines with baroquely curled edges, while those that break up the 1990 material have African patterns along the edges—a subtle reflection of people’s more open embrace of roots culture over the preceding decades.

The film’s most extraordinary aesthetic element, though, is its sound design, which is alternately boisterous and filled with pockets of silence, capturing the bustle of big city life as well as the perspective of its deaf characters. Booming, vibrating noises cut through the mix at any given moment, but there are often packets of dead air around those sounds; on-screen actions that you expect to be accompanied by a corresponding sound effect are entirely mute, as when someone knocks on Malaika’s door and she only registers it via a device that lights up to notify her that she has a visitor. The intricacy of the mixing is astonishing, and Davis’s thoughtfully thorough subtitling for accessibility even extends to noting sound effects and music cues in detail that recalls some of the audio-textual experiments of Jean-Luc Godard’s late period.

The immersive quality of the sound design is but one facet of the way that Compensation deftly uses intimate methods of character identification to encourage the viewer to imbibe the larger history lived through those figures. Through the specific experiences of Malindy, Malaika, Arthur, and Nico, we get ground-level glimpses of Chicago at the beginning and after the apex of its rise as a major cosmopolitan city, in both eras shaped in literal and cultural ways by its Black populace. The triumphs of self-expression and tragedies of ongoing marginalization are lived out through both romances, and the divergent paths of the two stories are linked in demonstrating the value of embracing hope and connection even in the face of inevitable loss.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.