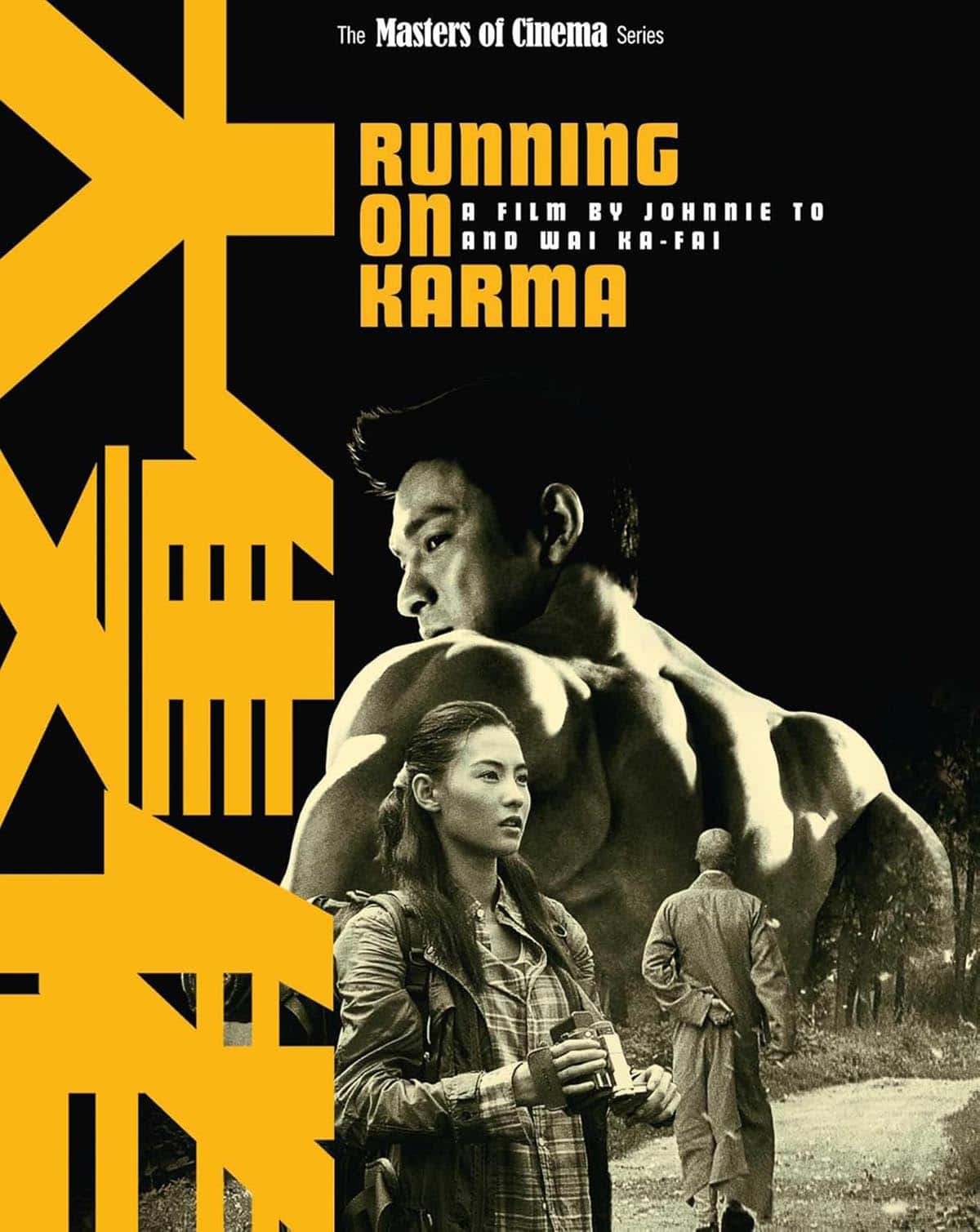

Johnnie To’s collaborations with writer-director Wa Ka-fai often defy genre classification. Among the strangest yet most compelling of their team-ups is 2003’s Running on Karma, a film that’s by turns a romantic comedy, a procedural thriller, and a wire-fu action movie. All of it is couched in a magical-realist philosophical rumination on the Buddhist notions of karma and the possibility of atoning for past sins.

Johnnie To’s collaborations with writer-director Wa Ka-fai often defy genre classification. Among the strangest yet most compelling of their team-ups is 2003’s Running on Karma, a film that’s by turns a romantic comedy, a procedural thriller, and a wire-fu action movie. All of it is couched in a magical-realist philosophical rumination on the Buddhist notions of karma and the possibility of atoning for past sins.

Andy Lau, sporting a ludicrous muscle suit, plays “Biggie,” a monk turned bodybuilder who left his order due to the stress of being able to see people’s past lives and thus know that negative karma would soon catch up with them in their current incarnation. Biggie finds himself drawn into the hunt for a serial killer whose contortionist abilities lead to a number of elaborate escapes and skirmishes with Biggie as well as cops. Paired with Criminal Investigation Department rookie Lee Fung-yee (Cecilia Cheung), he tracks the murderer via the ghostly imprints left by his victims, all while struggling with the visions he glimpses of Lee’s previous existence as a WWII Japanese soldier committing atrocities in Manchuria.

The film’s tonal shifts—sometimes within the same scene—could easily have derailed the story’s momentum, but To and Wai, working with regular Milkyway cinematographer Cheng Siu-keng, shoot the proceedings with a balletic sense of movement that finds a visual unity between the moments of broad comedy, metaphysical debate, and romantic tension between Biggie and Lee. Cheng’s trademarks of ultra-wide anamorphic compositions and cool green-blue color grading render the densely populated metropolis of Hong Kong as starkly lonely at times, with the frame’s negative space emphasizing the romantic tension between the leads and Biggie’s reluctance to reciprocate Lee’s more openly aired feelings out of fear of her impending fate. Eventually, Biggie’s visions of Lee’s doom prompt an existential crisis in the woman, one that leads her to embrace a Dionysian fatalism far away from the duty and danger of police work.

Just as Running on Karma seems set to run out on a whimsical note, it makes a radical last-act pivot that casts a funereal pall over the story and sends Biggie into a spiral of grief and rage. The odd genre mashup of the preceding 70 minutes is completely jettisoned in favor of a direct, harrowing confrontation with the film’s underlying themes of predestination and the sacrifices required to transcend the wheel of karma. It’s here that Running on Karma becomes something greater than an already singular genre exercise, instead offering one of the most forthright, vulnerable, deeply considered examinations of religious philosophy of any 21st-century film. One of its most resonant underlying themes is a rarely acknowledged undercurrent of much of Hong Kong’s legacy of martial arts cinema: that one’s greatest foe is always oneself.

Image/Sound

Eureka’s transfer comes from a 2K restoration that perfectly captures the delicate color balance and sharp details of Cheng Siu-keng’s cinematography. The seafoam greens and cool blues of backgrounds are all richly rendered, and there are no visible instances of crushing in darker nighttime scenes. Flesh tones are naturalistic, and textures are defined enough to make out the minute ridges of Andy Lau’s muscle suit. The soundtrack fills every channel with Cacine Wong’s percussive but elegant score while leaving plenty of room for ambient city noise and the occasional Foley effects of gunfire and the thudding sounds of the hand-to-hand combat.

Extras

Eureka’s disc comes with two commentary tracks, one by East Asian film experts Frank Djeng and F.J. DeSanto and the other by Djeng flying solo. There’s considerable overlap between the two tracks, which lay out Running on Karma’s themes, the stylistic trademarks of both Johnnie To and Wa Ka-fai’s work and the broader scope of the filmmakers’ careers, and the film’s butchering by censors for its mainland Chinese release. A new interview with Gary Bettinson, editor-in-chief of the Asian Cinema journal, covers Running on Karma’s social context and religious content, while an archival making-of featurette includes some behind-the-scenes footage. A booklet essay by critic David West unpacks the film’s unique blend of genres while placing it in the context of the larger history of the Hong Kong New Wave.

Overall

One of the greatest films in Johnnie To’s formidable canon receives a long-overdue video release in the West with a transfer that does justice to its magical realist beauty.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.