Tarsem Singh’s The Cell came at the end of a trend of 1990s noir films that merged the conventions of the genre with the aesthetics of music videos. Tarsem himself cut his teeth making music videos, most famously for R.E.M.’s “Losing My Religion,” and his first feature at times feels like an assembly of images that strives primarily for visceral impact, throwing cohesiveness to the wind.

Tarsem Singh’s The Cell came at the end of a trend of 1990s noir films that merged the conventions of the genre with the aesthetics of music videos. Tarsem himself cut his teeth making music videos, most famously for R.E.M.’s “Losing My Religion,” and his first feature at times feels like an assembly of images that strives primarily for visceral impact, throwing cohesiveness to the wind.

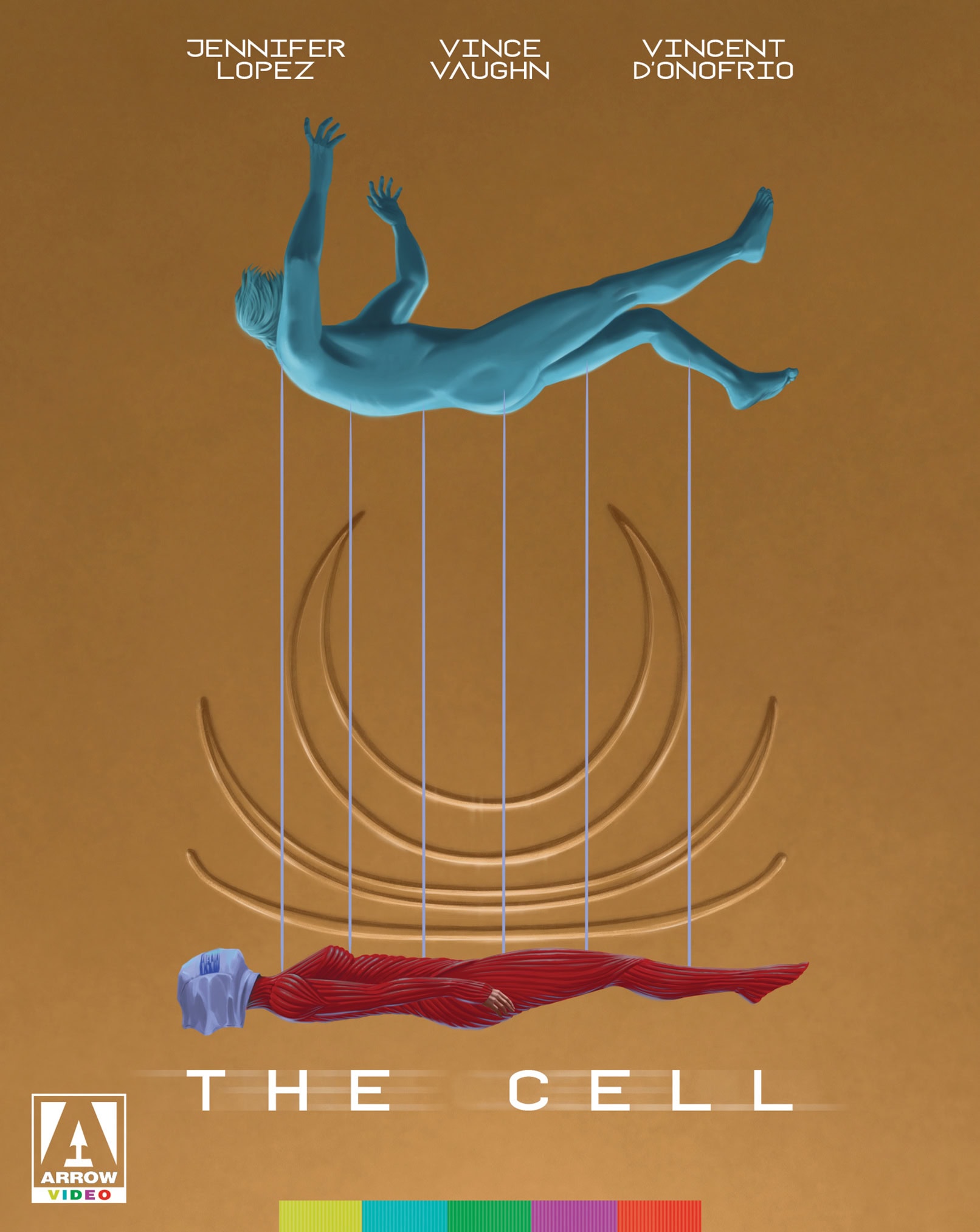

The narrative’s lack of connective tissue does make sense in the context of a film that largely takes place in a virtual reality rendering of the subconscious, the product of an experimental technology that becomes a law enforcement tool when the F.B.I. coaxes one of the tech’s researchers, Catherine (Jennifer Lopez), to enter the mind of captured serial killer Carl Stargher (Vincent D’Onofrio) in order to discern the location of a kidnapped woman set to be his next victim. In so doing, the story pushes past the boundaries of noir into psychological horror.

Even so, for all the hype over Tarsem’s artistry, so much of the film feels weighted by its allegiance to the likes of The Silence of the Lambs and Se7en. Written by Mark Protosevich, The Cell is also broadly concerned with the sexual pathologies motivating its serial killer antagonist, but it lacks the same interest in character that deepens those earlier films beyond mere flash. Catherine is effectively a blank slate of a heroine, defined solely by her innate skill at connecting with the subconscious of those whose minds she shares, while Carl is a run-of-the-mill monster forged from childhood traumas. The underlying staleness of the narrative constantly works against the vivid stylization of the material rather than being elevated by it.

Nonetheless, The Cell’s visual splendor is remarkable, and in no small part due to Tom Foden’s production design and Geoff Hubbard and Michael Manson’s art direction. The film’s dreamscapes are vast chambers of Escherian recursion, the brain rendered as architecture that’s simultaneously perfect in design and baffling in its lack of spatial coherence. Even the moments in which Carl’s mind takes Catherine into concrete memories of cramped childhood homes or the film cuts back to the antiseptic coldness of the virtual reality facility exude a hyperreal quality that highlights explosive bits of color like arterial reds and neon blues.

And, of course, there’s the absolutely breathtaking costume work by Ishioka Eiko, some of the most expressive and singular of her storied career. In the real world, the virtual reality suits that Catherine and patients must don before being neurolinked recall the ribbed red armor that Gary Oldman’s Vlad wears in Bram Stoker’s Dracula, for which Ishioka won an Academy Award). But Ishioka’s imagination takes full flight in the simulation, with increasingly elaborate, expansive outfits for both Catherine and Carl’s inner demon, all billowing robes and gowns with impossibly long trains that billow out behind the actors like giant wings.

Critics of auteurism cite the tendency to devalue the contributions of the various artists and craftspeople behind a film, but The Cell arguably illustrates the virtue of auteurism by the absence of an overriding directorial vision uniting the individual contributions of others. Only in the final half-hour, when the film gives in fully to its kaleidoscopic intensity as Catherine battles Carl’s evil side, does a unified sense of purpose emerge and give it a distinct identity of its own. A concluding flurry of images, which blend religious iconography, cyberpunk-esque aesthetics around the fusion of flesh and machine, and pop-transcendentalist spiritualism, establishes Tarsem as the 21st-century answer to Terry Gilliam, another maker of modern-day fairy tales consisting of phantasmagorical images that elaborate upon straightforward themes and morals.

Image/Sound

Arrow’s UHD release sports a Dolby Vision-boosted transfer, supervised by cinematographer Paul Laufer, of a new 4K restoration of both the theatrical and director’s cuts that renders the high-contrast, floridly chromatic images in all their beauty. The bloodletting and red costuming look particularly radiant, as do the greens and golds and even the blinding whites of Noh-like makeup that Vincent D’Onofrio’s character has in some of the film’s more surreal moments. The 5.1 audio is well distributed in all channels, making excellent use of surround sound for Foley effects and Howard Shore’s alternately dread-filled and boisterous score.

An accompanying 2K Blu-ray disc features an alternate version of the theatrical cut—presented in a 1.78:1 aspect ratio and different color grading—that was never released. Though it obviously lacks the same richness of color and lighting afforded by 4K and HDR, it boasts a stable, texture-rich transfer with no discernible video artifacts or print flaws.

Extras

This release includes a whopping four commentary tracks. An energetic track by Tarsem and one by members of the production team, among them Laufer, production designer Tom Foden, and composer Howard Shore, have been ported over from prior home video releases. The other two are newly commissioned. One is a breezy, effusive chat between film scholars Alexandra Heller-Nicholas and Josh Nelson, and the other a relaxed but informative conversation between screenwriter Mark Protosevich and film critic Kay Lynch. The latter is the most accessible and wide-ranging of the commentaries, as Protosevich thoroughly tracks the project from his first draft to the contributions of the crew in realizing the story’s visual potential.

Arrow’s release also comes with a host of other featurettes, including a new feature-length interview with Tarsem in which, among other things, he offers insights into his work, such as the formative childhood experience of spending time in Iran seeing films in a language he didn’t know and conceiving his own stories based on the images. In a separate in-depth interview, Laufer discusses meeting Tarsem when they were studying at the ArtCenter College of Design and how a collaboration between the two on a Nike ad led to them working on The Cell. Laufer then breaks down his approach to the film’s real and dream worlds.

Elsewhere, a video essay by critic Abbey Bender focuses on Ishioka Eiko’s costumes. Archival featurettes on Tarsem and the film’s visual effects are also included, as are a handful of deleted scenes. An accompanying booklet contains a number of new essays by critics Heather Drain, Marc Edward Heuck, Josh Hurtado, and Virat Nehru that cover topics ranging from the influence of music videos on Tarsem’s style to Jennifer Lopez’s work in genre cinema.

Overall

Arrow shines a spotlight on Tarsem’s flashy debut feature with a gorgeous A/V transfer and a generous assortment of new and old extras.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.