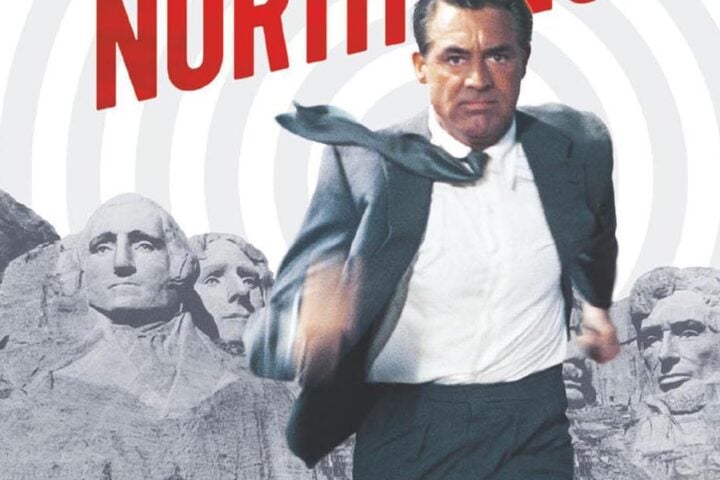

From the brisk strains of Bernard Herrmann’s Antonin Dvorak-inspired opening theme to its concluding gag of a honeymoon train speeding into a tunnel, North by Northwest is the apotheosis of Alfred Hitchcock’s exploration of the wronged man on the run and functioned in 1959 as a summary of the Master of Suspense’s career to date.

Cary Grant, wearing his gray suit like natural skin, embodies smug New York ad executive Roger O. Thornhill, an aging, gin-swilling playboy whose swiftly established m.o. in romance and work is “expedient exaggeration.” Poetic justice strikes as he’s incredibly abducted from the Plaza Hotel bar by the henchmen of an urbane master spy, Phillip Vandamm (James Mason, looking at Grant as if he’s a particularly bothersome housefly), who’ve mistaken him for an undercover agent. Framed for a killing at the United Nations, Thornhill runs a cross-country gauntlet of lawmen and baddies, with time for a sleeping-car tryst with an ambiguously remote blonde, Eve Kendall (Eva Marie Saint), who may doom or save him.

Ending the great director’s most fertile decade with juicy pop entertainment after the semi-realist grimness of The Wrong Man and the dreamlike romantic tragedy of Vertigo, the breezy, “light” North by Northwest is in danger of being pigeonholed as trivial Hitchcock because of screenwriter Ernest Lehman’s double entendre-laden badinage, Grant’s cool star turn, and the popcorn-friendliness of its celebrated action highlights: Roger’s scramble over a desolate prairie landscape to avoid the murderous attacks of a crop-dusting plane and his climactic flight from the villains with Eve across the presidential faces of the Mount Rushmore monument.

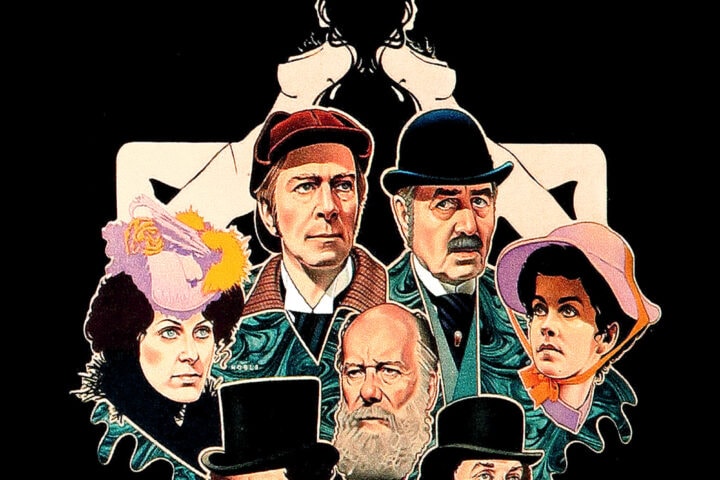

Yet along with the screwball staging of a corpse falling into Roger’s arms at the U.N. and his escape from an auction-room trap through prank bidding, many themes and motifs from more serious Hitchcock pictures can be found within it: the fluidity of identity (Thornhill’s embrace of play-acting the role of phantom agent “George Kaplan”), the burden of mother love (in the hilarious poise of Jessie Royce Landis as Roger’s mocking mom), and even coded-as-queer sadism (Martin Landau as Phillip’s enforcer, equipped with “woman’s intuition”).

Roger’s bitter revulsion at discovering Eve to be Phillip’s mistress recalls the darker variation of the spy-who-screwed-me scenario that Grant and Ingrid Bergman played with in Notorious. And Leo G. Carroll’s character, known only as the Professor, reads as an unusually bloodless American puppetmaster for Eisenhower-era Hollywood, one who defends the human sacrifice of his people or innocent Thornhills as the cost of winning wars, “even Cold ones.” In spite of Kaplan’s nonexistence, the intel chief is the story’s true empty suit.

Still, it’s the sleek and triumphantly assured surface of North by Northwest that’s allowed it to endure. Hitchcock sets his playful fantasy of spy chasing—with his most perfunctory MacGuffin gimmick ever (“Government secrets, perhaps”)—at landmarks like the U.N., Grand Central Terminal, and Mount Rushmore without pushing the subtext of chaos in the midst of placid national icons or the routine humming of transportation hubs and tourist meccas. The film is hugely pleased with itself, but you won’t mind given how funny and expertly calibrated it is. Both Hitchcock and Grant raise relaxed confidence to masterpiece level here, kidding the star’s persona when Thornhill is discovered creeping through a hospital room near the climax. “Stop!” blurts a nearsighted woman from her bed, before adjusting her glasses and sighing, “Stop.”

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.