Though the Holocaust had no one architect, Rudolf Höss remains singularly responsible for the speed and efficiency of the atrocities committed at Auschwitz, later emulated at the other Nazi death camps, thanks to his approval of the use of the deadly Zyklon B gas. And for his efforts at the first Auschwitz camp in Oświęcim, Poland, he was rewarded by being made commandant of death camp administration throughout the Nazi-occupied lands. This is the monster on full display in Jonathan Glazer’s adaptation of Martin Amis’s The Zone of Interest.

While the novel’s protagonist is named Paul Doll, Glazer chose to name Christian Friedel’s character Rudolf Höss. This immediately points to Glazer’s interest in bringing in the weight of a well-recorded historical character living in a specific place and time: the Höss household next to Auschwitz I in Oświęcim from 1943 to 1944. Much of the film follows the routine goings-on in and around the home, such as Rudolf enjoying the rowboat that his family gifted him for his birthday; his subordinates toasting their beloved boss; businessmen and engineers taking meetings in the living room; and Rudolf transmitting and receiving messages via telegraph.

Meanwhile, Rudolf’s boys play with their toy soldiers with an unsettling gravitas while his wife, Hedwig (Sandra Hüller), attends to visitors and scolds the help. At one point, Hedwig takes giddy, chilling pleasure at remarking that she’s known as the “Queen of Auschwitz.” And, indeed, the pristineness of the Höss home and its surrounding garden is nothing if not a testament to the efforts of a queen who takes her commitments very seriously. Life for these individuals is nothing if not undisturbed, until a promotion forces Rudolf to move away from his lovely home, and in an instant the man becomes a victim of his success.

Though Glazer shoots these scenes at a distance (as he did on Under the Skin, he hid the camera from his actors), The Zone of Interest never presents this family as neutral, normal, or completely divorced from the reality of Rudolf’s work at Auschwitz. Throughout these domestic scenes, the soundtrack of the Hösses’ daily lives is a reminder of the nightmare taking place just beyond the wall outside their home: The rumble of machinery fills the air, and occasionally gunfire and screams are heard. These sounds, relentless in their sense of evocativeness, give an extra layer of the uncanny to Höss’s already unsettling character, as this a man who willingly allowed his family to live mere feet away from the killing machine of his own making.

Rather than put gruesome imagery of death and cruelty front and center on screen, Glazer uses the film’s grueling sound design to represent the unfathomable scope of Nazi Germany’s crimes. It’s an aural hell punctuated by rhythmic interludes, courtesy of frequent collaborator Mica Levi, that suggests a dance party in Dante’s Inferno. To heighten the disturbing mood, Lukasz Zal’s camera often places a character in the dead center of the frame, and dollies alongside them as they walk to and fro, channeling the lockstep behind Adolf Hitler. Otherwise, though, it plays the stable voyeur with a lens angle just wide enough to feel unreal.

If the film operated just on that level, it would be easy enough to parse as a confrontation with Hannah Arendt’s observation of “the banality of evil.” But as The Zone of Interest progresses, we catch blunt glimpses of the anything but banal bureaucracy that makes the careers of men like Höss possible. The high command of the Nazi administration congratulate him for working his way up the ladder through hard work and good management, and, though Höss accepts such professional adoration, he finds himself bound by the red tape from the higher-ups and must accept his new role as the commandant of all death camps: a manager of middle managers.

Sure enough, the Volk-first promises of the Nazi regime and the Eigentlichkeit (“being one’s own”) dreams of philosopher Martin Heidegger were swept away by raw business rationality as the dominant working philosophy of Nazi leadership. As Höss knew all too well, those who actually tried to live the simple, traditional life promised to them by Nazi propaganda weren’t rewarded nearly as much as the obedient pencil-pushers of the modern German administration.

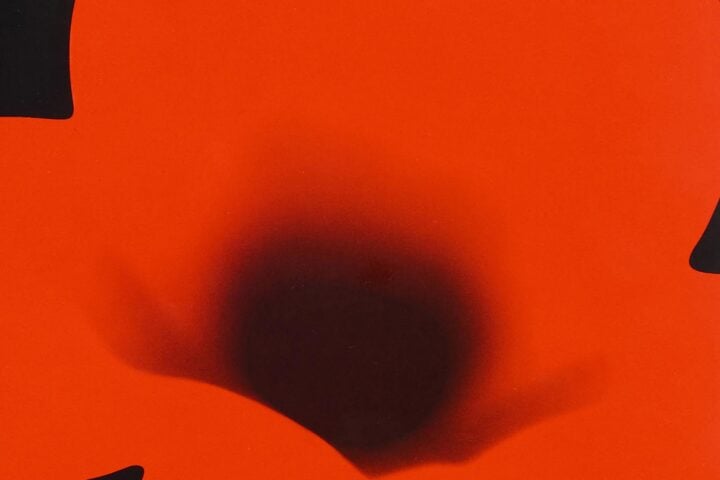

An early scene shows a living room meeting with engineers and architects selling Höss on the most efficient killing machine yet: a cylindrical, rotating system that loads in bodies, burns them, cools down, and disposes of the remaining materials, only to complete a full rotation and begin the process again without the need to stop. Efficiency means higher numbers, and higher numbers means more promotions. Meanwhile, the omnipresent red glow of the camp’s chimney peeks in through the windows of the house, mesmerizing the family late at night.

Across the film, as Rudolf reads bedtime stories to his children, images shot in monochrome by thermal-imaging cameras depict a young girl hiding fruits around a camp for prisoners to find—chilling interludes that attest to Glazer’s fascination, in more ways than one, with disruption. Glazer also has the audacity to end the film after the second act and immediately after a sequence that’s sure to provoke endless debate. This is no simple political message movie, nor is it even a portrait of one of the most horrific moments in history. Instead, The Zone of Interest is the hellish counterpart to The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, another film about the soulless march of the careerist’s life. Only in Glazer’s version, the march is a goose step.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.