Joel and Ethan Coen bring a touch of levity to their faithful adaptation of Cormac McCarthy’s relentlessly bleak 2003 novel No Country for Old Men, though it’s the type of nervous humor born from relieving immense tension. The Coens’ first film since their leaden remake of The Ladykillers is an exceptional return to their Blood Simple roots, offering up a crime saga in which money is almost as irresistible as bad choices are inevitable.

The Coens’ cynical streak finds its perfect complement in McCarthy’s gloomy tale of bibilical-scale chaos in 1980 Texas, and yet the filmmakers nonetheless locate the black comedy hidden within the acclaimed author’s terse, punctuation-sparse prose. Brusque exchanges and austere violence are the story’s stock-in-trade, with both elements so downbeat and harsh that they occasionally veer close to absurdity, thereby providing the filmmaking siblings with opportunities to wryly alleviate the oppressive despair and viciousness that hovers over the proceedings in the same way that the enormous western landscape and its weighty silence hang over its human inhabitants. As Tommy Lee Jones’s sheriff Ed Tom Bell says in reference to a particularly grim anecdote, “I laugh sometimes. ‘Bout the only thing you can do.”

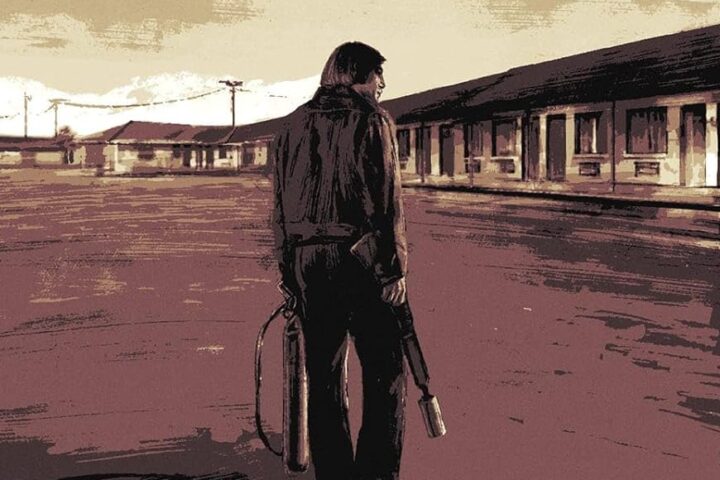

Hunting pronghorns out on the expansive Texas desert, Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin) stumbles upon a gruesome scene: vehicles abandoned, heavily armed men dead (aside from a solitary survivor begging for agua), a pickup truck flatbed full of heroin, and—a little ways off, next to another stiff—a suitcase full of $2 million in cash. A welder and Vietnam veteran, Moss discovers this mess by following a trail of blood spied on the dry, cracked earth, a perceptiveness that immediately marks him as a man attuned to the land’s rugged ferociousness, and thus makes his subsequent decision to take the cash and run a consciously foolish one.

Moss realizes that hard men will soon come for what’s theirs but absconds with the money anyway. Overstepping his boundaries at great risk, he’s something of a noir protagonist, albeit minus the romanticism, since the Coens—diligently following McCarthy’s lead—depict his momentous choice as the unwise but natural act of someone bred in a lunatic world. Unlike Bell, whose old-school values are ill equipped to confront the mayhem of the modern era, and very much like his pursuer, the psychopathic Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem)—who, later, will also ascertain knowledge from blood on the ground—Moss does what he does because he’s the product of a fundamentally out-of-whack environment.

This generational gap is intrinsic to No Country for Old Men, which laments with confused, terrified resignation the dawn of a new, more insane age—or, as one cop puts it, “the dismal tide.” Bell is the story’s nominal good-guy detective, attempting to figure out the who, what, where, when, and why of Moss’s disappearance and the carnage wrought by Chigurh, but he’s really just a street sweeper, left to clean up the mess left in these two younger men’s wakes.

The Coens’ efficient script proficiently captures McCarthy’s melancholic view of old-young disparities, whether it be Bell’s utilization of horses to scour the desolate desert for clues, or his bafflement at the callous disregard for the dead (and propriety) shown by a guy transporting corpses to the morgue. Meanwhile, their economical, decidedly un-flashy direction (mimicking McCarthy’s writing, and aided by longtime collaborator Roger Deakins’s beautifully severe cinematography) repeatedly conveys narrative undercurrents in entrancingly subtle ways, such that the plethora of animal carcasses, instances of man-versus-beast violence, and Bell’s yarn about a slaughterhouse mishap coalesce into a chilling portrait of anarchic interspecies warfare.

At the center of this maelstrom is the cattle stun gun-wielding Chigurh, a madman with a Prince Valiant bowl-cut and an expression both bemused and remorseless. His methodical comportment, like that exhibited by Moss when hiding his stolen loot in a motel room air duct, makes him seem innately in harmony with his surroundings. And yet the crazed glint in his eyes simultaneously casts him as an alien, an intruder recently arrived from Hades to tender unholy blessings (as during a lethal carjacking) and confession (to a gas station owner).

Bardem plays Chigurh like the calmest lunatic known to heaven or hell, and he’s never more frightening than when uttering, in his bizarro bass voice, the faux term-of-endearment “friend-o” to prospective prey. Chigurh’s stillness is emblematic of the Coens’ use of surface tranquility to conceal latent brutality, as well as an external reflection of his fatalism.

The villain’s habit of granting his victims a chance at amnesty via a coin flip turns out to be the sole exception to his governing belief that he’s incapable of affecting ongoing events, all of which he implies are byproducts of everything that’s come before. It’s a pessimism shared by No Country for Old Men itself, which makes clear the unavoidability and inconsequentiality of Llewelyn and wife Carla Jean’s (Kelly Macdonald) deaths—just two more drops of blood for the thirsty Texas earth—by keeping their murders off screen.

“You’re not cut out for this,” a drug kingpin’s hired hand (Woody Harrelson) tells Llewelyn. And though that’s technically true, the increasingly bullet-riddled Llewelyn remains better suited for his situation than his elders, such as a senior citizen who picks him up on the side of the road and—revealing an amusing lack of perspective—tells him, “Hitchhiking is dangerous.”

Thanks to its dour depiction of unreasonable, unstoppable evil, No Country for Old Men courts topical terrorism-related allegorical interpretations, even as it strives for Old Testament classicism. The Coens don’t shy away from McCarthy’s epically dark aspirations but their touch is a tad drier, affording their superb cast’s performances room to breathe, and allowing the action’s bursts of maliciousness to resound with greater impact.

An even more forceful impression, however, is left by the mournful epilogue, in which Jones’s weary, admittedly “outmatched” sheriff resigns in defeat to a universe he no longer comprehends. His recurring attempts to understand the modern condition through the filter of old tall tales are ultimately, pitifully futile. Yet if this failure represents an admission that the past, despite having begat the here and now, holds no keys to understanding the present, it also demands the creation of contemporary fictions to help make sense of the new world madness. With the masterful No Country for Old Men, the Coens and McCarthy give us one.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.