With the global rise of fascism, increasingly frequent and brutal climate crises, and an upcoming U.S. election that no one short of the Cenobites from Hellraiser is looking forward to, it’s no surprise that cinema in 2024 has been grappling with some heavy and heady existential themes. Fear and anxiety thus play a central role in numerous films on our list, both in relation to concrete concepts like sexual assault and corporate malfeasance or more nebulous ones embodied by sound or even left invisible altogether, though still strongly felt.

Even if the general feeling of impending doom is increasingly in the air, certainly not every filmmaker felt the need to surrender to nihilism or despair. Radu Jude’s Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World is, yes, a dystopic vision of modern society, but the aims of this raucous, wily satire are scarcely didactic. And the Ross brothers’ Gasoline Rainbow celebrates the power, joy, and necessity of human connection on the fringes of society.

Other titles on our list push back more directly against regressive responses to depictions of sex and sexuality on screen. Among them are films that challenge our preconceptions, dealing with issues of transness and asexuality (Jane Schoenbrun’s I Saw the TV Glow and Marija Kavtaradze’s Slow, respectively), while another, Luca Guadagnino’s Challengers, delights in the pleasures of simply bringing the sexy. In times of upheaval, cinema can be a comfort, an occasion for escape, but it can also force us to reckon with the chaos of our fragile world, while making us cherish the beauty that still exists within it. Derek Smith

Editor’s Note: Films that had a one-week awards-qualifying run in 2023 that we were able to screen ahead of publishing our 25 Best Films of 2023 feature were not eligible for this list.

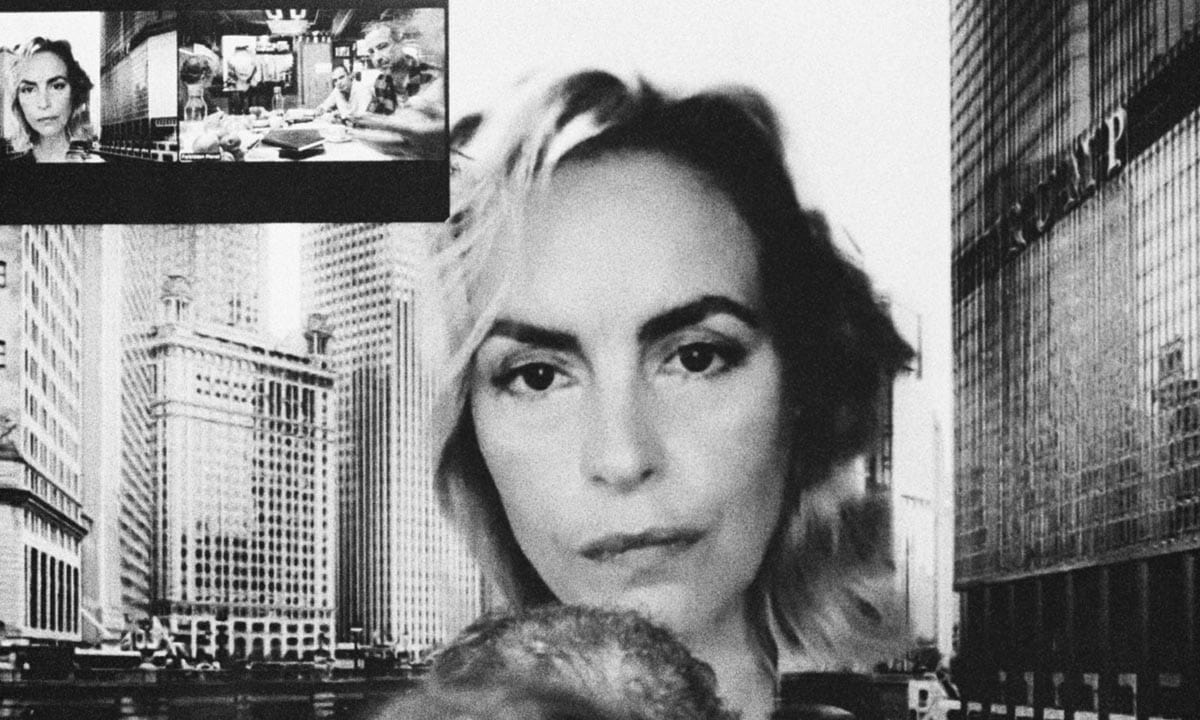

The Beast (Bertrand Bonello)

We’re all products of our time and circumstance, but how frequently do we push back against the forces—on the beasts both real and imagined—that keep us in anonymizing check? And, having taken such risks, how often do our own stories still end in tragedy? But then again, is the endpoint, our endpoint, the true crux of the matter? A line from Henry James’s 1903 novella The Beast in the Jungle, the loose inspiration for the disquieting The Beast, illuminates what is likely writer-director Bertrand Bonello’s main goal: “It wouldn’t have been failure to be bankrupt, dishonored, pilloried, hanged; it was failure not to be anything.” What the film most acutely captures, as its sprawling canvas expands and contracts before us, is the ceaseless cycle of two people failing to be over several lifetimes, in certain instances because of circumstances beyond their control, and in others because of their own purposeful inertia. Keith Uhlich

Challengers (Luca Guadagnino)

“Are we talking about tennis?” asks Patrick Zweig (Josh O’Connor) in a mid-aughts flashback as chugging, four-on-the-floor beats kick in to accompany an argument between him and his sure-to-turn-pro girlfriend, Tashi Duncan (Zendaya). It’s one of several instances in Challengers, an intoxicating showcase for the beauty and excitement of bodies in motion, set to a score that feels like a sweaty, thumping, barn-burning event in and of itself, where the characters make subtext into text. “We’re always talking about tennis,” she responds, but in Luca Guadagnino’s film, tennis isn’t just tennis—it’s sex, it’s power, it’s self-determination, or, as Tashi herself puts it at one point, “it’s a relationship.” What do we talk about when we talk about tennis? In Challengers at least, it’s absolutely everything else. Rocco T. Thompson

Chime (Kurosawa Kiyoshi)

Few would have guessed that Kurosawa Kiyoshi’s first horror film since 2016’s Creepy would come in the form of an NFT. Less surprising is that 45 minutes is all Kurosawa needs to put the genre’s output over the last eight years to shame. Chime concerns a self-absorbed cooking teacher (Yoshioka Mutsuo) who begins hearing the titular noise after a student (Kohinata Seiichi) is driven to madness while complaining of the same. The chime soon emerges as another of Kurosawa’s disease-like avatars of evil spreading inexplicably across society. Despite the project’s ultra-contemporary origins, Kurosawa arrives at his scares the old-fashioned way: a command of on- and off-screen space, light and shadow, and movement within the frame so total as to suggest an unknowable malign presence hovering over the images at all times. You’ll find no dot-connecting backstories or tortured trauma metaphors here, only a master filmmaker plunging you into incomprehensible terror, one brilliant formal choice at a time. Brad Hanford

Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World (Radu Jude)

Radu Jude’s Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World presents a nightmare vision of modern life. At the center of it is Angela (Ilinca Manolache), an overworked Uber driver and production assistant who’s tasked with conducting auditions with working-class employees of an Austrian furniture company who were injured on the job. The film’s plot, inasmuch as it has one, ultimately hinges on a man left partially paralyzed in a car-related accident, so it’s fair to say that Jude has vehicles on his mind. His camera observes them as economic necessities, environmental hazards, physical dangers, and, perhaps above all, unsightly detritus cluttering modern cities, embodiments of our dependence on technology. This is a film that listens avidly to what a cross section of ordinary citizens have to say about the war in Ukraine, Putin, Viktor Orbán, Jewish and Romani people, poverty, exploitation, and any other subject that would come up naturally in the course of visiting people in their homes. Seth Katz

Dune: Part Two (Denis Villeneuve)

Denis Villeneuve’s Dune: Part Two doesn’t play up the oddity of Frank Herbert’s setting but its history, conveying the thousands of years of human life between our own time and the novel’s in order to lend the political systems at war with each other more significance and legitimacy. Neither David Lynch’s Dune nor SyFy’s miniseries came close to capturing the awe-inspiring terror of Arrakis’s colossal sandworms, which here burst from the ground in volcanic eruptions of sand and so radically disrupt the landscape that watching them roll along the surface is like seeing billions of years of tectonic shift compressed into seconds. In a time when so many blockbusters mistake grandiosity for scale but limit their own spectacle with flat, open-matte compositions crafted in post-production, Villeneuve’s Dune films offer an object lesson in the visual splendor made possible by meticulously storyboarded minimalist maximalism. Jake Cole

Evil Does Not Exist (Hamaguchi Ryûsuke)

Evil Does Not Exist’s chief setting is Mizubiki Village, a small and isolated countryside community that’s far enough from Tokyo to offer a relief from the clutter and freneticism of city life but close enough to be easily reachable by city folk. Precisely because it’s so beautiful, the community is destined to be gobbled up by developers as a vacation paradise for the wealthy, and Hamaguchi Ryûsuke’s elliptical narrative charts the beginning of this invasion. Had the townsfolk been pitted against the glamping developers, or Takumi (Omika Hitoshi) and Takahashi (Kosaka Ryuji), one of the representatives hired to sell the glamping project to the locals, been allowed to bond and teach one another life lessons, Hamaguchi might have let us off the political hook, comforting us with fantasy. Curtailing his narratives, seizing up his action, which he foreshadows with the clipped-off score and strange tracking shots, Hamaguchi forces us to reckon with the industrialization of nature—and stew in it. Chuck Bowen

Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga (George Miller)

George Miller tends to approach the people he films like objects, fixating on some aspect of them that brings out their larger-than-life humanity, making them effectively mythic. This scalpel-like focus on the iconic possibilities of the individual, something surely shaped by Miller’s years studying and practicing medicine, helps to ground his mammoth flights of fancy, of which Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga has enough to fill several battle-ready tanker trucks. Here, it’s as possible to be moved by the very realistic clink of the heroine’s (Anya Taylor-Joy) necklace against a rock as it is by a patently false-looking yet exceedingly painterly time lapse in which a cliffside sapling sprouts outward and upward toward the sky. Though the film’s greatest special effect might very well be Chris Hemsworth as Dementus, who speaks to Miller’s enduring aptitude for utilizing the ridiculous to achieve the sublime. Keith Uhlich

Gasoline Rainbow (Bill Ross IV and Turner Ross)

Bill Ross IV and Turner Ross’s Gasoline Rainbow is an unusually poetic road film, as it has less in common with cut-and-paste teen party flicks than it does with the existentially freighted sensibilities of The Endless Summer, Two-Lane Blacktop, and even The Outwaters. Its teenage characters are rendered with unusual realism, while the imagery has the resonance and intensity that speaks of the resources and planning that’s typically associated with fictional films. It feels simultaneously “of the moment” and retrospective—a subtle yet formally extravagant teenage daydream. The trip that drives the film is less about getting loaded and laid—these teens don’t seem especially interested in sex—than marking one’s place in time. The shock of Gasoline Rainbow springs from the viewer realizing how rarely teens are allowed to be earnest in movies. These kids are poignantly nice, and the Rosses have cannily shaped the film so that their depth of character arises gradually throughout the 110-minute running time. Chuck Bowen

Ghostlight (Alex Thompson and Kelly O’Sullivan)

Kelly O’Sullivan and Alex Thompson imbue the paradoxes of performing arts so deeply into their film Ghostlight that it even extends to the title. In a poetic sense, the light stand that illuminates an unpopulated theater isn’t for human eyes. It’s to appease or rebuff spirits, depending on who’s asked. But in a practical sense, the ghost light exists to help the living—mostly to avoid a fate like falling into the orchestra pit and joining the dead. Life subsumes legend for O’Sullivan and Thompson in a worthy follow-up to their previous collaboration on the small-scale humanist triumph, 2020’s Saint Frances. Their ambition broadens significantly in Ghostlight, though their firm footing in sincerity and simplicity isn’t diminished in the slightest. The creative and life partners deliver a moving apologia for the value of theater by exploring its central contradiction: a performance is an act of honesty, not deceit. Marshall Shaffer

How to Have Sex (Molly Manning Walker)

The title of Molly Manning Walker’s feature-length directorial debut seems to promise a self-help guide to navigating the knotty ins and outs of physical desire. And given how it starts, with ready-to-party besties Tara (Mia McKenna-Bruce), Skye (Lara Peake), and Em (Enva Lewis) touching down in the coastal town of Malia in Crete, Greece, for their first holiday abroad, one might also anticipate that a redux of Harmony Korine’s Spring Breakers is afoot. Writer-director Manning Walker, though, has cooked up something far less ironic and fragmentary with How to Have Sex, though like Korine’s film, it’s interested in how the prospect of hardcore partying doesn’t transform from fantasy into nightmare in a flash. Rather, it oscillates from one to the other simultaneously, creating a gradual, narcotizing effect that makes sorting out one’s emotions, especially when they’re being newly felt, next to impossible. Clayton Dillard

The Human Surge 3 (Eduardo Williams)

Exhibiting a deliberately fragmentary aesthetic that sought to emulate the context-free disorientation of life mediated through laptops and phone screens, Eduardo Williams’s The Human Surge earned him the Golden Leopard at 2016’s Locarno Film Festival, as well as no small amount of bemusement and scorn from other quarters. The idea that such an obtuse experimental work could have any franchise potential inspired the jokey title of the filmmaker’s latest effort, The Human Surge 3. Though mostly unrelated to its predecessor, the film shares its jarring, hyperlinked structure and focus on the leisure time and everyday routines of unmoored, underemployed youths in liminal settings around the world. While its globe-trotting sense of wonder shows the joys of offline existence to be as profound and vivid as they ever were, its simultaneous expression of boundless possibility and stagnant futility recalls nothing so much as the chaotic, alienating realm of cyberspace that both birthed and shaped it. David Robb

In a Violent Nature (Chris Nash)

The concerns of writer-director Chris Nash’s In a Violent Nature are thrillingly cryptic and evocative. After an hour-plus of Johnny’s (Ry Barrett) splatterific bloodletting, only this flesh-rotted executioner and shellshocked final girl Kris (Andrea Pavlovic) remain. A vengeful and conflagratory battle appears to be in the offing. But then Kris makes a choice far removed from what a character in her position might normally do, seemingly breaking the cycle of violence. More likely, she defers the surely apocalyptic consequences of Johnny’s rabid resurrection to some not-so-distant future date. The climax is then daringly given over to an extended conversation between Kris and her rescuer, a woman played in a pointed bit of meta-casting by Friday the 13th: Part 2’s Lauren-Marie Taylor, about the oft-inexplicable interplay between the human and natural worlds. It’s a curveball that feels exactly right in context and fully in conversation with the film’s many unnerving aesthetic and thematic ambiguities. Uhlich

Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell (Pham Tien An)

Compared to his numbed reaction to the present, Thien (Le Phong Vu) finds motivation in retracing the past he left behind when he moved to Saigon, and Pham Tien An’s Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell patiently observes him rekindling prior relationships in his rural hometown, whether checking in with village elders or running into an ex-girlfriend (Nguyen Thi Truc Quynh), who’s since become a nun. One gradually gets the sense that, though the man left his home to get away from a feeling of being suffocated, he feels far more at ease in the realm of nostalgia than he does in the uncertainty of the present moment. Thien may feel cut off from the world, but Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell is deeply in harmony with it, from its masterful sound design that fills in off-screen space with ambient noises, to its observant long takes, to the deference it shows to the wisdom and experience that elders can impart on the young. Cole

I Saw the TV Glow (Jane Schoenbrun)

Jane Schoenbrun’s I Saw the TV Glow is the rare movie that deserves being called Lynchian—not for any overt weirdness, but for its mastery of ineffable, almost subliminal unease to depict repression and the toll it takes on one’s psyche. Expanding on We’re All Going to the World’s Fair’s subtle illumination of gender dysphoria, Schoenbrun at first delicately illustrates the way that pop culture can be a catalyst for self-discovery among loners and misfits, only to slowly dig deeper and reveal the limits of displacing one’s questions of identity onto an object of obsession. Unable or unwilling to confront the questions that his fixation prompts, Owen (Justice Smith, always standing agonizingly on the verge of physical and emotional implosion) lets life slowly pass by as the world starts to seem increasingly alien and increasingly inescapable. I Saw the TV Glow regularly blurs the line between reality and fantasy, but it’s in the starkest and most reflective moments that the film feels the most like cosmic, mind-shattering horror. Cole

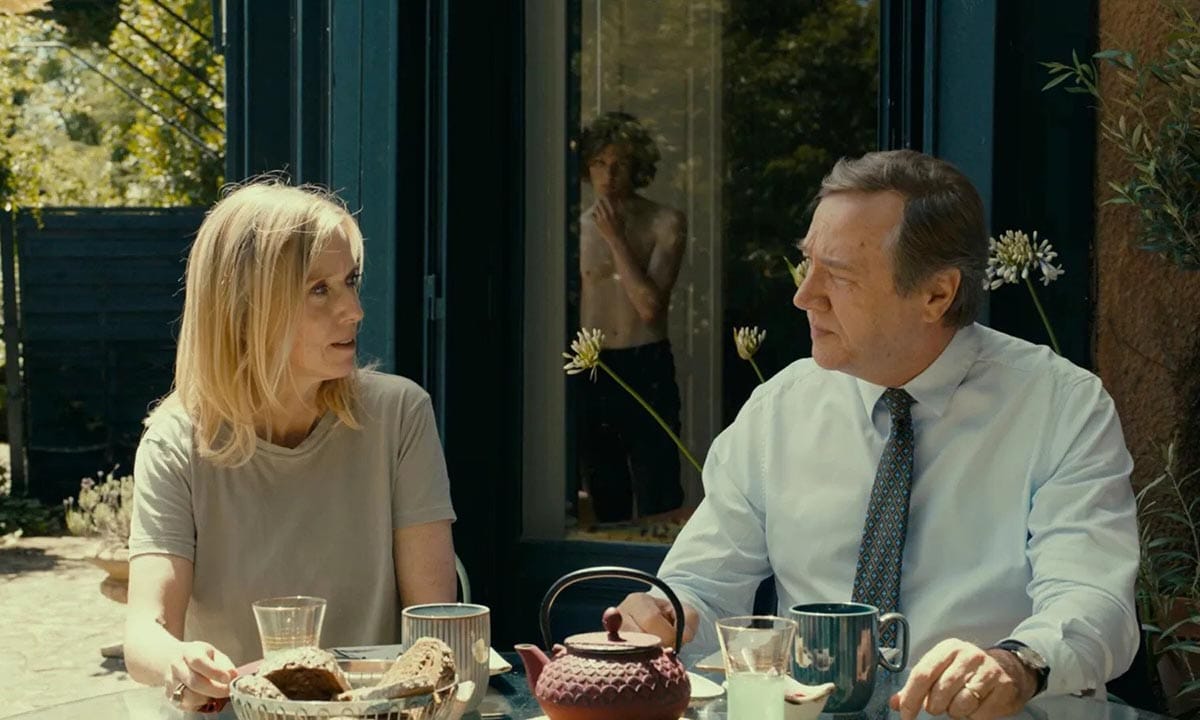

Last Summer (Catherine Breillat)

In Last Summer, Catherine Breillat brings her icy, unwaveringly sober sensibilities to one of the most common of American pop cultural sex fantasies: a teenager’s tryst with a MILF. At their home in the suburbs of Paris, we see Anne (Léa Drucker) with her older husband, Pierre (Olivier Rabourdin), who’s successful but scans as dull and schlubby when compared to his trim and attractive wife. If we know Last Summer’s narrative ahead of time, we may feel as if an equation is being established that’s typical of older-woman, younger-man sex fantasies: that a boring husband gives a wife license to get her groove back elsewhere. But we’d be wrong. Elsewhere, Breillat doesn’t mar the realtionship between Ann and Théo (Samuel Kircher), Pierre’s 17-year-old son, in the harlequin clichés a daydream. The reality of this situation is always compacted by Breillat’s committed and very pointed objectivity. No one in Last Summer is sentimentalized, and Breillat denies neither the ickiness of this affair nor its potential pull. Bowen

Limbo (Ivan Sen)

Ivan Sen’s Limbo, about one man’s investigation of a 20-year-old outback cold case murder, does for the crime mystery what Rodrigo Moreno’s The Delinquents did for the heist film: Both transform their respective genre by redefining its relationship to time. Extending its concern with the aftershocks of colonialism in Australia, the film tackles aftermaths in a more general sense. If the attrition of time has rendered justice, if not meaningless, then beside the point, there may still be a way for Travis Hurley (Simon Baker) to reconcile the victim’s brother, Charlie (Rob Collins) and sister, Emma (Natasha Wanganeen), who became estranged in the aftermath of their sister’s murder, and in the process come to grips with the ghosts in his own past. Sen’s attention to how one mystery erodes over the long-term draws out the deeper, structural contestations and affinities—not unlike the forces that shape a mineral over eons—of his characters, their society, and the land on which they find themselves. William Repass

Pictures of Ghosts (Kleber Mendonça Filho)

At the heart of Kleber Mendonça Filho’s argument in Pictures of Ghosts is how much of the resources and capital that allowed for a thriving cinephilic culture in Recife, Brazil, was stripped away in the 1970s and ’80s, and committed instead to making the city into a tourist destination for wealthy foreigners. One of the first pieces of archival footage we see features Janet Leigh and Tony Curtis on vacation in the city (with little Jamie Lee in tow), a flash of Hollywood glitz that carries uncomfortable associations in context. At one point, Mendonça Filho comments that “fiction films make the best documentaries,” which sounds like a banal truism until the final scene, an unexpected departure from nonfiction that slyly implicates the filmmaker in his own commentary. As always with Mendonça Filho, to reflect reality isn’t enough, as cinema has to find its own truth, even if it takes some imagination to get there. Hanford

Robot Dreams (Pablo Berger)

Poised to become many things to many people in a way few movies can, Pablo Berger’s effortlessly heartbreaking and life-affirming Robot Dreams opens on a nighttime shot of the Brooklyn Bridge, the Manhattan skyline in the distance. The year is 1984, and the Twin Towers loom, figuratively and literally, as ghostly figures. Berger’s breathtaking adaptation of Sara Varon’s graphic novel of the same name isn’t about the towers in any specific fashion, but about a world in which change is the only constant, life of any kind is at the mercy of randomness, and joy and melancholy are in ongoing symbiosis. In other words, our world—albeit one populated here, not by humans, but by anthropomorphic, humanoid animals. The ups and downs experienced by Dog and Robot throughout, whether together or apart, speak to the multitude of ways life surprises us, giving and taking away in equal measure. Rob Humanick

The Settlers (Felipe Gálvez)

Felipe Gálvez’s feature-length debut, The Settlers, takes place in an independent Chile at the end of the 19th century that’s still defined by its period of colonization. Any story that directly confronts the wanton brutality of colonization and manifest destiny in the Americas perhaps inevitably draws comparisons to Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, a Grand Guignol of frontier extremity. Alexander MacLennan’s (Mark Stanley) callously detached carnage against indigenous South Americans blatantly recalls some of the more wanton violence of that book, but Gálvez takes an inventively circumspect approach to depicting that slaughter. The Settlers also recalls McCarthy’s sense of pitch-black humor, which is so intense that it threatens to absorb all light. Gálvez’s satire lacerates the contradictions and hypocrisies of European racism and how its convolutions would pit even fellow whites against one another. Cole

Slow (Marija Kavtaradzė)

Across Slow, Marija Kavtaradzė presents Dovydas’s (Kestutis Cicenas) asexuality neither as a crutch nor some sort of mental block that he must overcome. The film steadfastly remains a character-driven piece, homing in on the intricacies of its protagonists’ psychologies and engaging with their subtle emotional shifts as they become more intimate with one another. And it’s through the sheer specificity of these observations that Slow accrues its most penetrating insights into the nature of love, sex, and desire. Elena (Greta Grineviciute) is a free-spirited young woman used to traditional sexual relationships, while Dovydas is new to experiencing an emotional connection strong enough that he’s willing to work to build something beyond mere friendship. And as the characters traverse unexplored terrain and deal with myriad frustrations, Kavtaradzė gives equal credence to Elena and Dovydas’s experiences, from their most bitter disappointments to their most emotionally gratifying highs. Smith

Honorable Mention: Art College 1994, Babes, Civil War, Coma, Concrete Valley, The Devil’s Bath, The First Omen, Here, Hit Man, Io Capitano, In Our Day, Janet Planet, Music, The Old Oak, Samsara, Sasquatch Sunset, The Shadowless Tower, Skin Deep, Thelma, and Tuesday

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.