That Memoir of a Snail is a catalog of bleakly unfortunate events shouldn’t come as a surprise to those who’ve seen Adam Elliot’s previous feature, Mary and Max, and his Oscar-winning short Harvie Krumpet before it. This stop-motion animated film—part seven of a “trilogy of trilogies” (three short shorts, three long shorts, three features)—opens with Grace Pudel (voiced by Charlotte Belsey as a child, then Sarah Snook when older) witnessing the last gasp of an elderly pal, Pinky (Jacki Weaver). As she goes to scatter Pinky’s ashes in the garden, Grace narrates her life in a shy whisper to a pet snail, sparing no tragic detail.

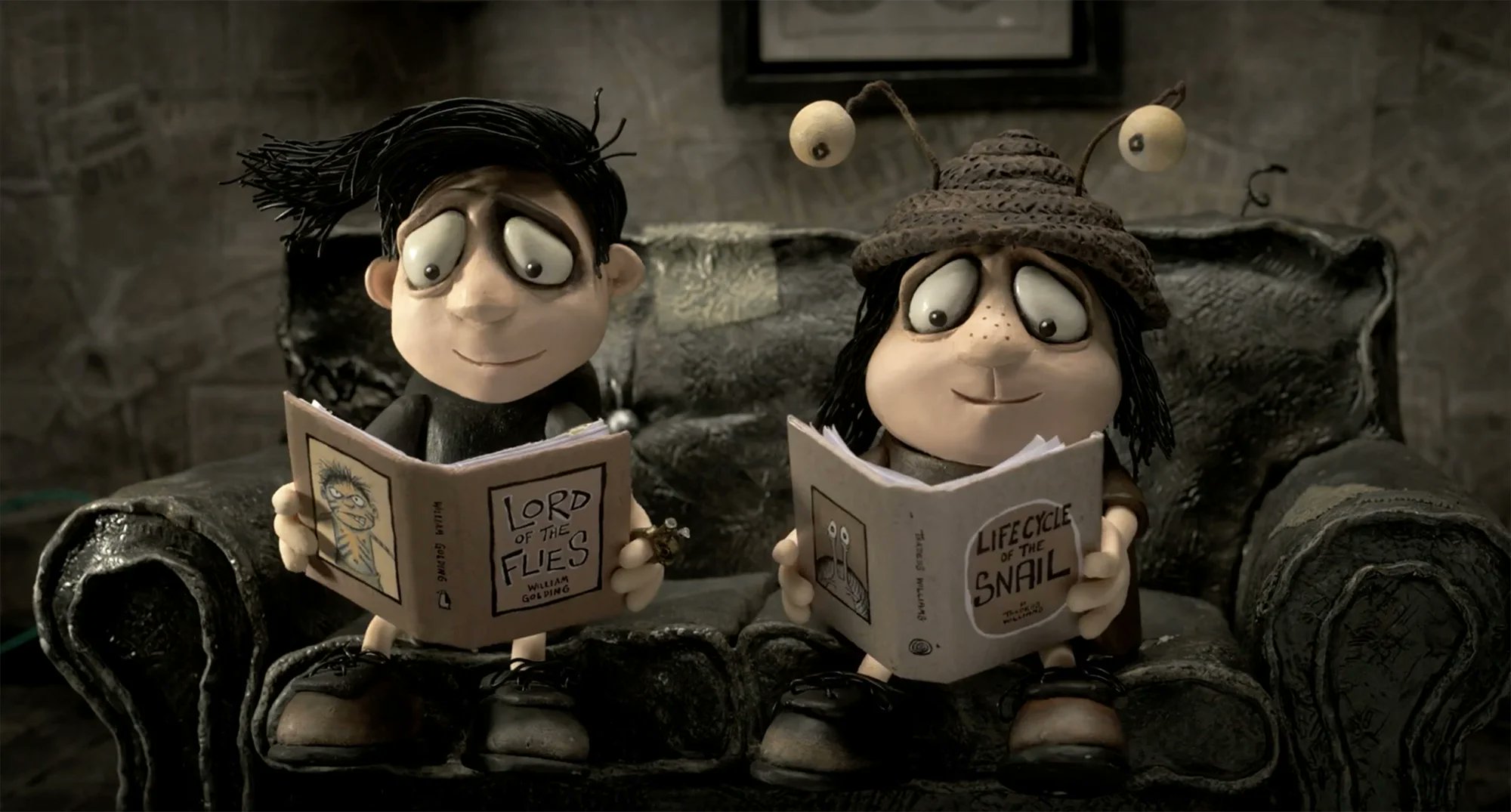

Grace’s mother died in childbirth, and her alcoholic father was left paralyzed from a traffic accident. She loves her twin brother, Gilbert (voiced by Mason Litsos as a child, then Kodi Smit-McPhee when older), a budding pyromaniac who defends her from school bullies, but even this relationship doesn’t last, as they’re separated and shipped off to foster homes at separate ends of Australia once their father passes. There’s a sense of grim inevitability to just about everything that occurs to Grace in the film, right down to her hoarding of ornamental snails.

Yet Elliot, whose work is no stranger to despondency, never allows the film to fully succumb to despair. Grace describes herself as a “glass half-full” sort of person, and her clear-eyed, matter-of-fact narration allows Memoir of a Snail to maintain a brisk, even somewhat light-hearted, tone throughout as she details the events of her life. Amid so much anguish, the moments of triumph, however small, and perseverance feel that much more like epiphanies.

As we’re propelled from one vignette to the next through her words, Grace rarely stops long enough to wallow in what would be quite justifiable sorrow. In a sense, she’s like the snails that she’s enraptured with, as they can only move forward. Grace’s affinity for them is so profound that she’s rarely seen without a homemade hat that imitates their eye stalks.

The meticulous clay world that Elliot and his team of animators have built, of course, is just as integral to conjuring Memoir of a Snail’s tone of whimsical misery. It’s heavily stylized, full of cramped architecture and characters with squashed human proportions. It’s also marked by a giddy profane-ness, from the frequent middle fingers to the displays of nudity.

Even as Grace loses herself in smutty romance novels, Elliot never indulges in the flights of fancy that many animated works employ as a shortcut to create visual interest. The film views its heroine in the details of her environment, and the more we take in the textures of this very real world, right down to background details like newsprint wallpaper and the patchwork lampshade of the twins’ childhood apartment, the more we’re caught up in Grace’s individuality.

Grace builds a metaphorical shell for herself with a room of hoarded snail memorabilia, allowing her to retreat from the world rather than wholly escape it. If Memoir of a Snail falters, it’s in the unchanging nature of the film’s narration-heavy structure. Even as Snook recalibrates the emotions of her voiceover, Grace’s life at its most passive and tragic is portrayed with similarly breezy descriptions as her personal triumphs, like when she manages to stand up for herself and generally come out of her shell. We’re only able to learn that some of her eccentricities are keeping her from living her life because the film directly tells us so, placing something of a clumsy asterisk beside what’s otherwise an evocative feat of visual storytelling.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.