By the time Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby concludes, we’re hardly left hankering for backstory. It’s the rare horror film that wholly explains itself without diluting the tension that it carefully builds. What, if anything, can a prequel bring to the table? If Natalie Erika James’s Apartment 7A is any indication, apparently not much, because aside from a few inventive dream sequences, the film’s potential never crystallizes outside of one 10-minute stretch that, unfortunately, is immediately followed by the credits.

The film follows Terry Gionoffrio (Julia Garner), a bit character in the original who appears in just two scenes—one of them as a corpse splattered on the pavement in front of the Bramford apartment building (a.k.a. the Dakota in real life). While Apartment 7A works hard to recreate the setting of Rosemary’s Baby, it isn’t beholden to the exact details of Polanski’s film. For one, rather than a drug addict plucked off the street, this version of Terry is a down-on-her-luck dancer struggling to land roles after a bad fall in the middle of a show.

In a fit of desperation, Terry trails theater producer Alan Marchand (Jim Sturgess) to the Bramford, where she soon finds herself under the care of Minnie and Roman Castevet (Dianne Wiest and Kevin McNally), the overbearing couple of elderly Satanists played in Rosemary’s Baby by Ruth Gordon and Sidney Blackmer. Not only do they set her up in a Bramford apartment down the hall from theirs, but they formally introduce her to Alan.

Yet even without being restricted to sticking to the letter of the original, Apartment 7A is marred by familiarity. Terry is essentially just Mia Farrow and John Cassavetes’s roles from Rosemary’s Baby collapsed into one, albeit with some gendered showbiz humiliation and a loudly ironic upbringing added to the mix. She’s both victim of a Satanic pregnancy conspiracy and a dubious beneficiary of fame, and to a degree that doesn’t quite make sense. (The death knell that pregnancy might have for a stage dancer’s nascent career is barely explored.)

The dynamic between Terry and her predatory boss is similarly undercooked, to the point where any parallel between Alan and, well, Roman Polanski could very well be pure coincidence. Rather than deepening or complicating the original work, Apartment 7A engages with it purely on franchise terms, as in how it foregrounds the Castavets for much of the runtime.

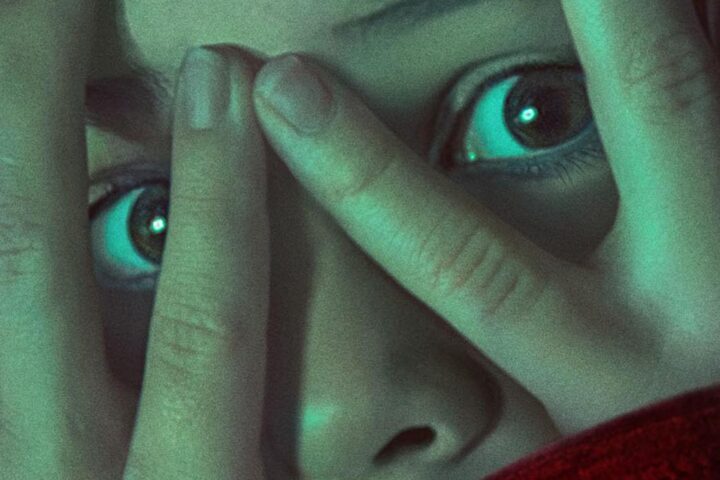

At best, the film’s showbiz backdrop is an excuse to add some neat musical iconography to Terry’s drug-addled dreams and hallucinations, but at worst, it’s a witless echo of whatever Rosemary’s actor husband is up to off screen in Polanski’s classic. And absent the original’s queasy spousal dynamics, it’s as if the prequel has settled for retreading the plot beats around the pregnancy and conspiracy, but with a flat, overly lit style that bears no resemblance to James’s lushly metaphoric vision for her debut feature, Relic.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.