Not long after the opening titles for Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema, the housemaid (Laura Betti) at an enormous, stately, and modern house in Milan is seen tending to fallen leaves, while a new guest at the house (Terence Stamp) smokes and reads on the nearby veranda. He’s absurdly beautiful. The maid is seized by an increasingly debilitating sexual attraction to the visitor: In the same moment she’s staring at his bulging crotch, he absent-mindedly lets some cigarette ashes fall onto his trousers. She rushes over to brush them off, and, newly possessed by a giddy, hyperactive spirit of her own making, goes into her private locker in the kitchen to plant kisses on the religious icons she’s pasted there, wordlessly admonishing herself for her lurid thoughts.

Resuming her care of the lawn outside, the woman enjoys no respite from her desires. What sets her off the second time isn’t the young man’s cock but his face, posed and framed unmistakably in the manner of a religious icon, the kind that depicts a saint or Christ gazing skyward, beset by spiritual, rather than carnal, yearning. It’s too much for her; face drenched in tears, she races into the house and pushes the kitchen gas hose down her throat. Seconds from death, she’s rescued by the visitor, who takes her to bed. Their embrace isn’t unfettered from the intimations of a holy benediction that have just been established.

In turn, and via different sets of circumstances, the visitor beds everyone else in the household: first the lanky, athletic son, Pietro (Andrés José Cruz Soublette); then the neglected mother, Lucia (Silvana Mangano); then the reserved, level-gazed daughter, Odetta (Anne Wiazemsky); and finally, after much inner turmoil expressed through sudden illness and frequent cutaways to blasted, volcanic landscapes, the father, Paolo (Massimo Girotti). Pasolini, like his countryman Michelangelo Antonioni, uses realist feints like natural landscapes, location filming, and an observational, largely anti-melodramatic timbre to construct an overall strategy that, paradoxically, produces dreamlike emanations, as if any surface could give way to the otherworldly, yielding only to a light touch. Hints, looks, and posturing convey much that isn’t seen or mentioned in this enigma of a film.

Pasolini, best remembered as an incendiary, outspoken, openly gay, Marxist, Catholic-turned-atheist filmmaker and writer, was less reluctant than Antonioni to use his art as a vehicle for his often-excoriating views. Most germane to Teorema, appearing during a year that’s often pointed to as the singular peak, just before the fall, of revolutionary fervor in postwar Europe, is the fact that Pasolini despised the bourgeois class—and the family that hosts Stamp’s mysterious visitor is nothing if not textbook Italian bourgeoisie.

Almost as soon as the visitor has circled the quintet, the hyperactive mail carrier (Ninetto Davoli) who implores the housemaid to smile early in the film returns, this time with a letter that will compel the visitor to bid the family adieu. Each of them, in turn (and now with no insinuations of sex), confides in him how they’ve changed, not in appearance or, necessarily, action, but in intangible, philosophical ways. Could Pasolini so hate the property-owning class that he gave them a perfectly conceived totem of his desire? What ensues is the consequence not only of the visitor’s departure, but of the fact that he gave them something unnameable, and they will, to varying ends, pursue that thing all the way to the end of the road.

Teorema is a film that’s short on incident but not at all lightweight or unserious. Pasolini’s idea of structure is to build with moods and reinforce with context, a risky approach that pays off as the film’s second half becomes stranger and stranger without ever seeming to lose focus. Rather than becoming diffuse, Teorema gains power by pressing down hard on the mystery of its conception. Having departed for points unknown (hinting at an Antonioni-esque “was he ever really here?” scintilla of additional mystery), the visitor never returns, but the idea of him has, somehow, seized permanent control of each of the five, casting them to different winds.

The first in the house to topple is Emilia, who departs by train to her home village, without a word. (In a hilariously dark and loaded gesture, she’s replaced by an almost identical maid, also named Emilia, played by Adele Cambrea.) Odetta begins to lie motionless in bed, one hand clenched unceasingly, eyes open, until she’s carted off in an ambulance. The original Emilia takes a seat at the edge of the village square, refusing to move or utter a word. The townspeople, all known to her, slowly begin to believe that she’s been transformed into a kind of religious manifestation, and regard her with awe. Some bring their afflicted children, hoping she can transmit miraculous cures. Others bring her cheese and wine, and Emilia tells them that she only wants to eat weeds plucked from the roadside.

Pietro buries himself in his project, oil painting on transparent materials. He experiences an initial epiphany when he regards his own incompetence as a visual artist, yet, instead of abandoning the endeavor, redoubles his efforts, delivering to himself heated lectures concerning the necessity of, and the means toward, disguising incompetence through arrogance and self-regard. He, too, has been touched by some manner of holy spirit. Originally filming the character as a jaunty, bounding figure of fun (and kind of a double for the simian mail carrier), Pasolini fills the frame with Soublette’s newly grim and determined face, which now seems imperceptibly older, leeched of joy but energized by purpose. As any artist will do when they’ve got enough time and near-limitless financial backing, Pietro holes up in a spacious studio, adorns its exterior windows with anti-establishment slogans, and attempts transgressive expressions of art like urinating on a blank canvas.

We follow the outward-spinning paths of Lucia and Paolo—her toward desperate sex with increasingly sketchy young men, him toward a more total self-erasure. It’s around this point, when Paolo wonders if he should give his factory away to his workers, that we realize that a sophisticated, film-length trap is now closing all around us. The perplexing events of the prologue, in which unnamed men discuss a factory owner who’s given away his entire operation to his workers, are contextualized as a flash forward, and we learn (or have likely already intuited) that Paolo is that factory owner, and his story has been leading to that crucial decision. Yet a throwaway line from the prologue, a hypothetical “whatever the bourgeoisie does is wrong,” suggests that even if a titan of industry destroys or gives away everything, and wanders the wastes, nude, screaming into the void, it’s not enough. The suggestion that the family’s every gesture is insufficient, incorrect, even pathetic, may be harsh, but a little analytical distance mitigates what may seem cruel in Pasolini’s judgments. The title of the film (Theorem in English) allows for a lens of interpretation, namely that this is a parable with a philosophical-mathematical spirit. The lives of these people are written on a chalkboard.

Pasolini, whose mind had a depth and breadth that remains inadequately measured to this day—mostly thanks to the notoriety of his final film, Salò—never commits to anything so easily reducible as a condemnation of Teorema’s central family. Pietro’s pretentious self-regard is kind of contemptible, but Lucia and Odetta’s suffering isn’t. Emilia, it might be argued, attains holiness as she buries herself in a construction site, her tears forming filthy pools next to her face, but Paolo’s ultimate destination may be the most tragically fitting of all. Wandering the billowing wastes that we’ve glimpsed now and then since the start of the film, the now-nude factory owner has renounced everything but has no one to witness his labored martyrdom—not even a crowd to hurl stones at him, like the mythic Wilbur Mercer in Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Pasolini the atheist, anti-bourgeois filmmaker grants the family a visitation, maybe from something beyond their understanding, and even as he plots out their subsequent ruination, corruption, or debasement, it’s evident in the attitudes and weighted imagery in the film that he feels it. He feels all of it.

Image/Sound

Compared with the BFI’s 2013 Blu-ray release, this disc boasts a comparably healthy bitrate, but the Criterion Collection has also made clear and decisive choices that distinguish their release. The difference can most obviously be seen in skin tones and contrast levels: The BFI disc’s image indulges in a judicious application of dark pools of shadow, whereas on the Criterion, details in faces, decor, and architecture are sharp and vivid—never blown out. The close-ups of Soublette, late in Pietro’s arc, needed this sometimes-brutal sharpness, the better to indicate his transformation from carefree boy to consumed young man. But if that doesn’t illustrate it well enough, consider Silvana Mangano’s eyeliner, as we often lose her haunted, hungry eyes on the BFI transfer, while she’s shaded just right on the Criterion.

The disc provides two Dolby Digital monaural tracks, one in Italian, the other in English. (We hear Stamp speaking in his own voice in the latter.) The English track rates a little bit less than the Italian; there’s a lot less nuance in the translation, and the overall sound field seems a bit tinny, in comparison, but for the completist, it’s got library significance. Both tracks are clean and well-managed, especially allowing for the different registers of music, headlined by Ennio Morricone’s unusual score, as well as the terrifying Lacrymosa from Mozart’s “Requiem.”

Extras

Pasolini doesn’t strike one as his own best salesman, and so, the two-and-a-half minutes of 1969 interview footage where he gives cryptic answers to broad questions about Teorema may not give you the best pre-film introduction, though, peering from behind his Kiarostami-like shades, he makes a compelling figure, impish yet somehow deadly serious. The 2007 Terence Stamp interview, which runs about 30 minutes, fares a little better, with respect to the film. Stamp, as commanding and charming—and, occasionally, a bit cheeky—as he ever was, relates anecdotes that build on the story of the film’s genesis and production, though he sometimes seems stymied, even skeptical, of Pasolini’s whole, enigmatic, cranky persona.

So, it’s left to the other two supplements to do the heavy lifting. Center stage is the Robert Gordon audio commentary track, which has been ported over from the BFI disc, like the Stamp interview. Gordon’s prepared remarks are erudite, diving deep into a scene, or adding context regarding the source material, Pasolini’s life and preoccupations, and other assorted details. While the track is well-structured, and highly educational, Gordon will often simply describe action or mise-en-scène that’s already plain to see. Still, an essential listen.

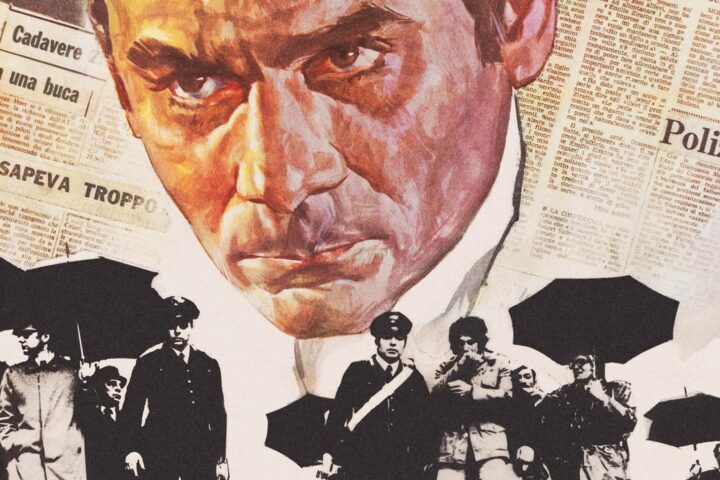

Newly recorded for this release is John David Rhodes’s video essay. Rhodes, author of Stupendous, Miserable City: Pasolini’s Rome, gives a brisk yet well-mounted 16-minute summation of Teorema’s inner workings and fundamental mysteries, with a particular focus on the cast. While one may hypothesize that Stamp’s ethereal beauty is key to powering Pasolini’s semi-parable, semi-schematic fantasy, Rhodes moves the other direction, offering that Stamp’s movie-star wattage conceals Pasolini’s hands as he moves the game pieces around. What lends credence to this is that Rhodes shades in the backgrounds and associations carried by each of the other principal players, including Pasolini’s own mother, Susanna Pasolini, who plays a crucial role in the descending arc of Emilia’s story.

The crown jewel of this release, though, is the brilliant essay by James Quandt, “Just a Boy,” which, in a few, dense pages, manages to move mightily not only through the film’s texts and subtexts, but where it stands in relation to Pasolini’s poetry and personal politics.

Overall

The overall girth of Criterion’s Teorema release seems more dutiful than exalted; perhaps more of a ruckus could have been raised for one of the most singular and thrilling films of its era. Just the same, their decision to produce a transfer that’s rich in detail where previous releases erred on the side of waxy, dark accents is reason enough to rejoice.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.