The Gowanus Houses, a public housing project in the heart of Boerum Hill, hasn’t changed much since Spike Lee filmed Clockers there a quarter century ago. In a borough of Brooklyn that’s been blasted wide open and transformed by gentrification and billions upon billions of dollars in development capital, the land and buildings within the NYC Housing Authority’s purview tend to remain, inexplicably perhaps, frozen in time. Still, it’s hard not to notice the glaring contrasts between the Gowanus Houses and some newer bulwarks, like the Barclays Center, the Red Hook IKEA, or the impenetrable and unobtainable houses occupied by the swells of nearby Cobble Hill and Brooklyn Heights. These monuments, and more, symbolize the city’s indefatigable efforts to eradicate “the ghetto,” as well as everyone living there, from a vision of the future that bears no scars but, paradoxically, requires regular blood sacrifices to expedite the progress of empire.

The Gowanus Houses, a public housing project in the heart of Boerum Hill, hasn’t changed much since Spike Lee filmed Clockers there a quarter century ago. In a borough of Brooklyn that’s been blasted wide open and transformed by gentrification and billions upon billions of dollars in development capital, the land and buildings within the NYC Housing Authority’s purview tend to remain, inexplicably perhaps, frozen in time. Still, it’s hard not to notice the glaring contrasts between the Gowanus Houses and some newer bulwarks, like the Barclays Center, the Red Hook IKEA, or the impenetrable and unobtainable houses occupied by the swells of nearby Cobble Hill and Brooklyn Heights. These monuments, and more, symbolize the city’s indefatigable efforts to eradicate “the ghetto,” as well as everyone living there, from a vision of the future that bears no scars but, paradoxically, requires regular blood sacrifices to expedite the progress of empire.

In the film, after crossing the artery of Flatbush Avenue, patrol cars and homicide detectives from the 88th Precinct on Classon Avenue regularly rain down on the Gowanus Houses like Luftwaffe bombers over London. We first see them harassing courtyard dealers known as “clockers.” Clumsy and naïve plainclothes narcotics police and uniformed patrolmen harangue them using brusque and ineffectual methods, shouting things like “Tell us where the drugs are!” and “I know you’re carrying!” It isn’t long before you notice that shaking these kids down for their concealed supply is just a pretext, whereas the cruelty—the forced strip searches, the dehumanizing language, the fondling of genitals—is the point.

Lee establishes this pressure-cooker milieu in a handful of brisk minutes that conceal a highly nuanced, ambivalent attitude toward the clockers. Before he does so, the film’s title sequence—a collage of crime scene photographs (recreations, it turns out) of murdered black people scored to R&B singer Marc Dorsey’s “People in Search of Life”—establishes a grave context that will envelop everything that follows. What matters, above all, beyond deeds sordid or noble, is that the black bodies in those photos, which had been alive only a moment before, were desecrated, and it makes precious little difference why, or by whom.

It’s through this prologue that Lee establishes his authority over Richard Price’s material (the film is based on his 1992 novel, which he and Lee adapted for the screen). One of our great crime fiction writers, Price is rightly celebrated for his command of geographic detail and street talk (especially when it comes to his police characters). He supplies Clockers with its whodunnit/why-dunnit foundation, but the structure built on top of it is Lee’s own. What emerges is a slice of life beset by a rising sea of lethal hazards and an assortment of stressors that can lay siege to an unlucky individual all at once, like a symphony in hell.

Strike (Mekhi Phifer) just happens to be that individual. Afflicted, like a Paul Schrader protagonist, with a stress-induced bleeding ulcer that he nurses with chocolate milk, Strike is the jagged cipher at the center of Clockers, irredeemable in the eyes of several of the story’s moral arbiters. Yet, compared to the likes of neighborhood kingpin Rodney Little (Delroy Lindo) and the killer Errol Barnes (Lee staple Thomas Jefferson Byrd), the latter disintegrating from AIDS, Strike is just a babe in the woods.

Early in the film, Little orders Strike to carry out a hit on a rival, a big-talking operator, Darryl Adams (comedian Steve White), who’s clocking from within a popular restaurant called Ahab’s. The hit, like the murder at the center of Price’s 2008 novel Lush Life, is rendered in ellipsis, leaving the characters, and us, to process clues and circumstances after the fact, and at a considerable disadvantage. Strike’s brother, the more accomplished and straight-edged yet equally troubled Victor (Isaiah Washington), confesses to the murder, but lead detective Rocco (Harvey Keitel) suspects there’s a lot more going on than he’s being told.

Far more than the murder story and what unravels in its wake, Clockers gains its power as an accumulation of pressures and clanging horrors. When a violent incident occurs later in the story, its aftermath flooding the narrative morass with even greater volatility, Lee masterfully delivers a singular, bold centerpiece: Rocco narrating and coaching Shorty’s statement. The sequence, a projection of Shorty’s imagination prompted by Rocco, turns the projects’ courtyard into a theater of exaggerated proportions and angles, with Rocco in the driver’s seat.

In the novel, this passage begins and ends across a few pages, and there are no stylistic flourishes to speak of, but Lee casts it in a role similar to Radio Raheem’s murder in Do the Right Thing—a cataclysm that releases an enormous amount of built tension and, in the same instance, accelerates and amplifies many of the story’s worst-case scenarios. And, having already shown us the complex architecture of the Gowanus Houses drug trade, with its interlocking machinery of power plays and strenuously managed appearances, an endlessly demoralizing grind that both sides of the law participate in, the sequence takes us on an unexpected detour into a kind of queasy puppet theater, paradoxically revealing the wounded heart that’s been beating underneath everything, all this time.

While Clockers would be Lee’s first real brush with the policier, it hasn’t been the last, so it’s worth pondering how he uses technique and storytelling to convey his conflicting attitudes toward the New York Police Department, and American policing in general. Neither he nor Price pull any punches in depicting cops, of all ranks, as casual, habitual racists, indulging in horrifying language; in the final minutes, we overhear a uniformed beat cop describing the projects as a “self-cleaning oven”—an image not without obvious, and chilling, connotations. In lockstep with his younger partner, Larry Mazilli (John Turturro), Rocco has all the earmarks of the asshole cop: He drinks on duty, spits racial epithets carelessly and cavalierly, and even sets up Strike to get whacked in order to produce a desired effect.

What does Octave say in Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game? “Everyone has their reasons.” And everyone is the hero of their own tale, even asshole cops. Rocco doesn’t pursue a path of compulsive self-destruction like the title character that Keitel played in Abel Ferrara’s Bad Lieutenant, a mere three years before this, but if you watch carefully, you’ll see that Clockers uses Strike’s hellbound—and hell on Earth—trajectory to deflect our attention away from details about Rocco’s path that aren’t trumpeted as loudly. Scene by scene, he pivots away from each normal source of motivation as he tries to use brute force and battlefield thinking to push through the mysteries of the case. At first, the Darryl Adams murder is routine. When Victor declares himself as the prime suspect, Rocco can’t accept it, and pivots to pursuing what he thinks is the real truth, against the express wishes of his precinct, and his peers, who think he’s out of his mind for choosing not to throw the book at Victor. Is he pursuing truth at any cost? Truth, as a principle, goes right out of the window when Shorty kills Errol, and Rocco (at the behest of NYCHA cop André, played by Keith David) feeds Shorty the best possible statement, with only an incidental relationship to the facts.

You could hypothesize that truth is tricky, grimy, complicated, and that Rocco isn’t so much a bringer of truth as an agent of justice, even as it displeases his superiors and perplexes his partner. What he does for Shorty, and, by association, the deceased Errol, qualifies as a kind of frontier justice, dispensed under the table and off the books. Nevertheless, justice in the Darryl Adams case eludes Rocco as the case simply collapses under the weight of an 11th-hour revelation delivered by Strike and Victor’s mother. Still, Rocco persists, but toward what? He delivers Strike to Penn Station, releasing him into the wilds beyond the Hudson River. No wisdom or reason can explain why Rocco made this call—not routine, not truth, not justice. As a long-term plan, it doesn’t even withstand a few minutes of scrutiny. Yet it seems to the viewer, and all parties involved, except the men who want Strike dead, that the problem of Strike has no tenable solution, though this is the one comes the closest.

It cannot be known, except to himself, what compels someone like Rocco. He might describe it as a grain of righteousness that never altogether dissolves, even as it flows along conflicting rivers. At the end of the road, as the two men sit in Rocco’s car, next to the entrance to Penn Station, Strike asks Rocco, “What made you give a shit?” It’s the one pointed question that’s directed at Rocco throughout the film, the one question that requires an inward gaze, but he declines to answer, instead telling Strike that if he ever sees him again, he’ll bust him on trumped-up charges. During quieter moments, Clockers shows Strike enjoying moments of stolen quiet, taking solace in his model train set. It’s in these moments that we glimpse his inner life. But what does a guy like Rocco see when he looks inward? That grain of righteousness? Or just a void in the shape of another dead body on the sidewalk?

Image/Sound

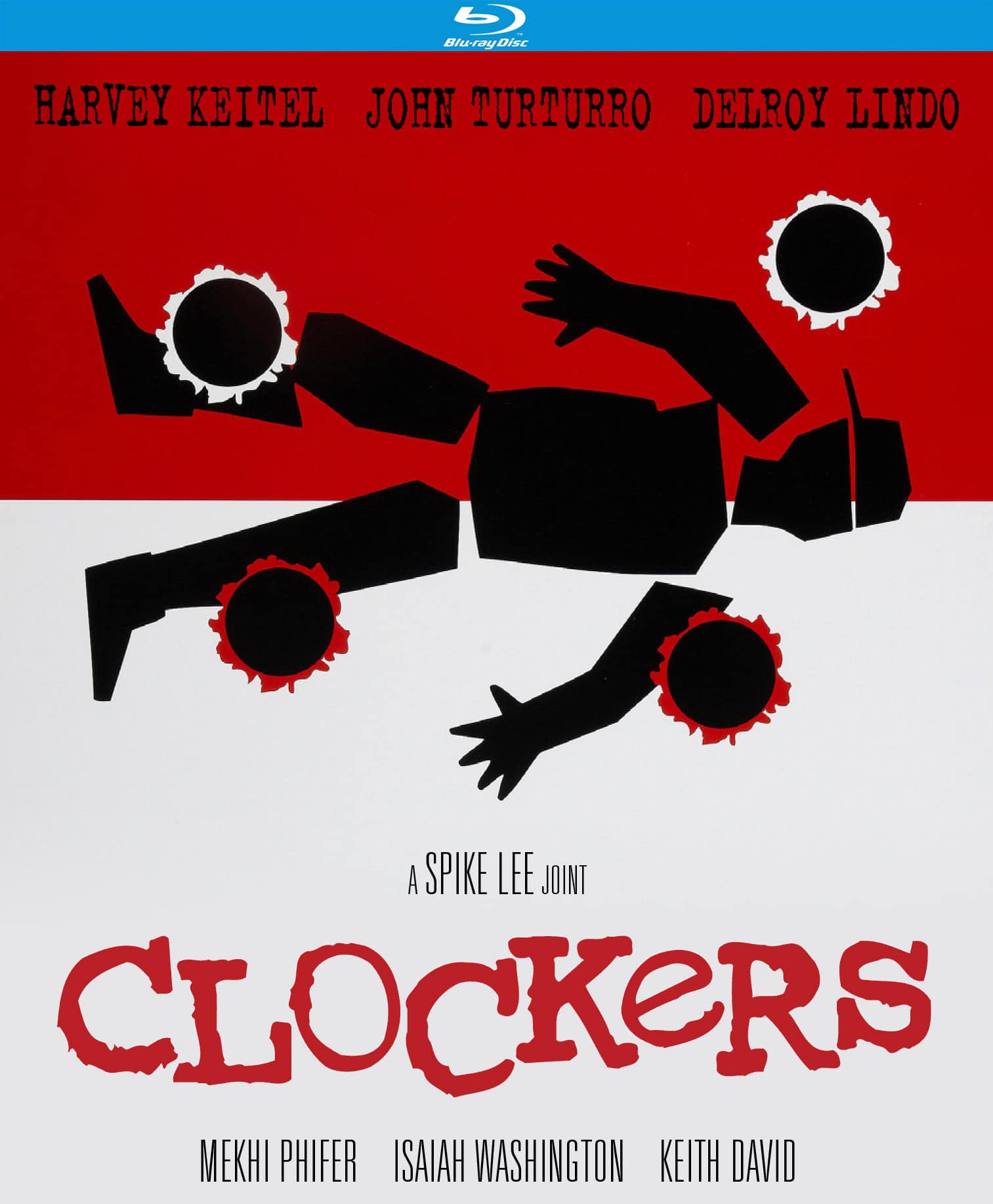

Clockers marks a specific convergence in Spike Lee’s career, when his confidence as a filmmaker aligned with the boldness of his flourishes. Perhaps emboldened by Oliver Stone’s JFK, he and cinematographer Malik Hassan Sayeed indulge in mixing up film stocks and F-stops to produce just the right visual cacophony to convey the hellworld that is Strike’s adventures in sewing and reaping. This Blu-ray edition preserves the film’s tricky aesthetic—a summary effect of Klieg lights and flashbulbs providing unreliable illumination of black flesh, while the rippling humidity of daytime supplies no real comfort. Of the two included audio tracks, I preferred the 2.0 stereo, for its richness and depth, to the 5.1 surround, but your mileage may vary depending on your setup.

Extras

Kino is making a big push to get several Spike Lee joints on Blu-ray, so it’s hard to criticize them for not releasing deluxe editions. Alongside a set of trailers for other recent Kino Studio Classics releases sits an indispensable audio commentary by Vanity Fair’s K. Austin Collins, easily one of the brightest and most erudite film critics we have. Collins builds on his personal relationship with Lee’s films, Clockers in particular, and produces a considerable amount of revealing details and contexts that enrich the viewing experience.

Overall

As Clockers is one of the best filmed-on-location New York crime movies, its absence on Blu-ray has long been a glaring oversight, which Kino now makes right.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.