As revisionist westerns go, Viggo Mortensen’s The Dead Don’t Hurt is more contemplative than most. The film has its share of violence, brutality, and injustice, but its protagonists respond stoically to life’s misfortunes, where lust for revenge animates other heroes of the genre. And with a clearly defined focus on the lives of women and immigrants against the backdrop of the Civil War, Mortensen develops thematic material introduced in his directorial debut, 2020’s Falling, which pitted a relentlessly bigoted patriarch against his gay son.

The Dead Don’t Hurt also employs a fragmented timeline like the earlier film. In Falling, frequent flashbacks effectively rendered the confusion of the film’s dementia-suffering father. In The Dead Don’t Hurt, Mortensen has dialed back the aggressive cross-cutting in favor of a more straightforward editorial grammar. But the non-linear construction here serves both to generate dramatic irony and to ensure that the story’s pieces don’t fall into place until near the end—less for the purpose of suspense than undercutting our expectations of where things are going.

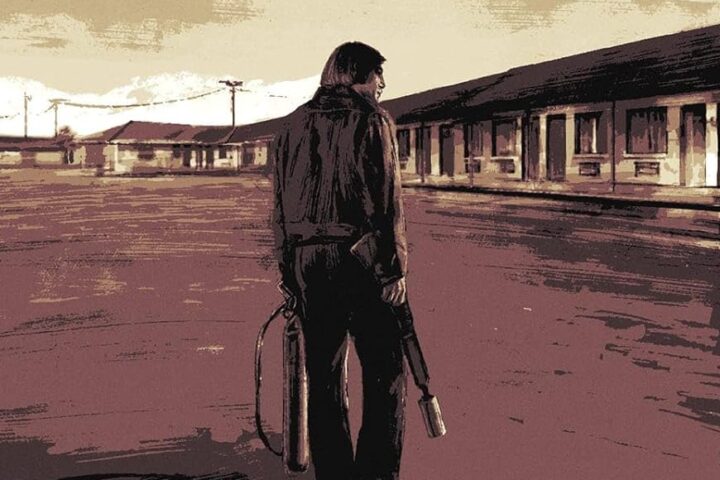

Mortensen himself, looking gaunt but sturdy, plays the role of Olsen, a Danish immigrant who’s ascended to sheriff of the fictional Elk Flats, Nevada. The film opens with the death of his companion, a French-Canadian woman named Vivienne (Vicky Krieps). Later, after watching an obvious miscarriage of justice engineered by the town’s mayor, Rudolph Schiller (Danny Huston), and a powerful rancher, Alfred Jeffries (Garret Dillahunt), who frame an innocent man for Alfred’s son’s (Solly McLeod) killing spree, Olsen turns in his badge and leaves town. While occasionally checking in on his journey through a barren landscape, the film mainly proceeds linearly through the past, showing us how Olsen and Vivienne met and built a life together.

Krieps turns in a layered performance as a staunchly independent woman with visions of Joan of Arc. Vivienne’s brashness occasionally gives way to moments of vulnerability, and as the story progresses, it becomes clear that her inner fortitude isn’t matched by physical strength. When Olsen decides to enlist in the Union army to fight against slavery, he leaves Vivienne exposed.

Enter McLeod as the film’s snarling villain, Weston, who, in case it wasn’t clear that he’s the bad guy, at one point pummels a honky-tonk pianist for playing a pro-Union song. A newcomer, McLeod fails to locate any humanity in this one-dimensional role, playing Weston as if he knows he’s the villain of the piece. Weston sets his sights on Vivienne when she starts working at a bar owned by his father, and it’s not hard to imagine where things go from there.

When the film resembles a traditional western—basically any scene set in a saloon—Mortensen’s writing brings little originality or vitality to the material. Far more effective and disarming is the love story, and in particular the way things play out after Olsen returns from the war, when he has to face Vivienne and deal with the consequences of his absence. Some clunky dialogue aside, their relationship is the emotionally authentic through line of The Dead Don’t Hurt.

Ultimately, though, the film’s didacticism lets it down. As in Falling, Mortensen has a point to make about America, and this dictates the direction of the story. Olsen, who’d already fought invaders in his native Denmark, has no hesitation about adopting the Union’s cause as his own: “This isn’t your country,” Vivienne tells him at one point, to which he responds, “It is now.” The ruin that comes to his life and Vivienne’s, as a reward for his loyalty and commitment to doing what he sees as the right thing, comes across as glibly schematic, an ugly lesson. Furthermore, while Mortensen’s aim of making a western led by a woman may be admirable, it would be even more so if the story didn’t hinge on her brutalization, as so many putatively feminist films do.

There’s a sincerity to Mortensen’s work here that helps paper over some of his less imaginative choices. He demonstrates his artistic vision at every moment (he also composed the score), whether through a vertiginous angle over Vivienne’s grave or the reflection of light that flashes on Weston’s face while he brandishes a knife. If only that vision were applied to something more than a maudlin political statement, it might find a fuller, more satisfying expression.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.