Dibbern and Larson discuss how writing about film led them back to writing about themselves.

It’s a moving, witty, at times almost trance-like work traversing age, aging, sickness and death, as well as joy, gratitude and wonder.

One of Zink’s missions is to navigate how the absence of one life continues to play on those left alive.

The novel succeeds, in part, by rejecting uncomplicated constructions of blame or causality.

Hoberman discusses how the art of filmmaking, and the business of moviegoing, influenced, mirrored, and altered Reagan’s presidency.

Tremblay discusses how horror can be a progressive, hopeful way to understand the world.

Thomas Harris’s novel fathoms man’s depravity in ways that are at once spectacularly horrifying and mordantly amusing.

If you’re in a band, the Beatles taught you everything, whether you know it (or admit it) or not.

Throughout, Ellis waves a broadsword at political correctness.

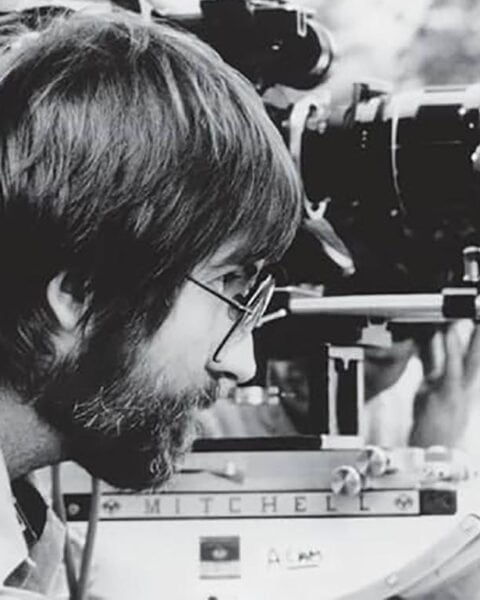

Stratton goes beyond the production of Sam Peckinpah’s film, on to its impact and reception and legacy.

Édouard Louis’s latest is strong as a portrait of a family unable to communicate through anything but volatile, toxic outbursts.

Lynch’s paintings are beautiful yet macabre, mysterious and rich in the tactility of the methods of their creation.

By the end, the lesson we’ve learned is that the stories we tell ourselves about the past have always been revised from a previous draft.

Throughout this remarkable book, what seizes the characters’ attention, and ours, often has the dissimulated air of a revelation that’s still in the midst of disclosure.

There’s something uncommonly relaxing about many of McPhee’s patient elaborations of things known and unknown.

Piero’s visual style, indicates the irrevocability of the past, even though the book is often a fairly straightforward record.

Even as The Lonesome Bodybuilder approaches its conclusion, new and winding pathways unfurl.

Grann not only conveys something of Antarctica’s haunted landscape, but also the boundless awe that it occasioned in Henry Worsley.

The novella is an absorbing read, but its vicious, downtrodden qualities are sometimes overwrought.

At its best, History of Violence about the tension between desire and danger, between passion and destruction.

Vicuña is populated with characters even more thinly veiled than Gore Vidal’s were 60 years ago in The Best Man.