Notable as it is for evoking a kind of cosmic banality, writer-director Bruno Dumont’s anti-space opera The Empire runs into same the pitfall as many parodies of its kind. However intriguing its premise may be, the film becomes tedious in practice, as what few homegrown ideas it has to offer lack for substantial development. Built almost entirely on the very tropes that it sets out to undermine, The Empire mainly succeeds at hollowing out itself.

A present-day fishing village in Northern France would seem to be an unlikely battleground for a galactic conflict between good and evil, and it’s this incongruity of setting and story that forms a basis for The Empire. The 1s and the 0s, as the opposing forces call themselves, must take human form to properly exist. On the 0 side, there’s the fisherman Jony (Brandon Vlieghe), father to the Wain—a toddler destined to become the supreme evil—and Jony’s new girlfriend, Line (Lyna Khoudri). And on the 1 side, there’s Jony’s good counterpart, Jane (Anamaria Vartolomei), and her keen yet bumbling apprentice, Rudy (Julien Manier).

Jony serves Belzébuth, Emperor of the 0s, a formless black blob later embodied as a local tour guide (Fabrice Luchini), while Jane and Rudy serve the Queen of the 1s (Camille Cottin). The plot kicks off when Rudy beheads the Wain’s mother with an energy sword, which triggers an ancillary storyline involving an investigation by two gendarmerie officers (Bernard Pruvost and Philippe Jore, reprising their roles from Li’l Quinquin and Coincoin and the Extra-Humans).

No self-disrespecting space opera stints on spacecraft design, and The Empire is no exception, expressing its parodic themes through the combatants’ motherships: The 1s traverse space in a gothic cathedral with an interior like the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, while 0s get around in spacefaring Palace of Versailles. Even as the literal binary snipes at the moral dualism (perhaps also the CGI special effects) that space operas tend to traffic in, the ship designs reframe the opposition as overinflated, since, architecturally, they’re not even that different. Dumont shows up the “futuristic” space opera as Christian cosmology dressed up in ray guns and FTL travel.

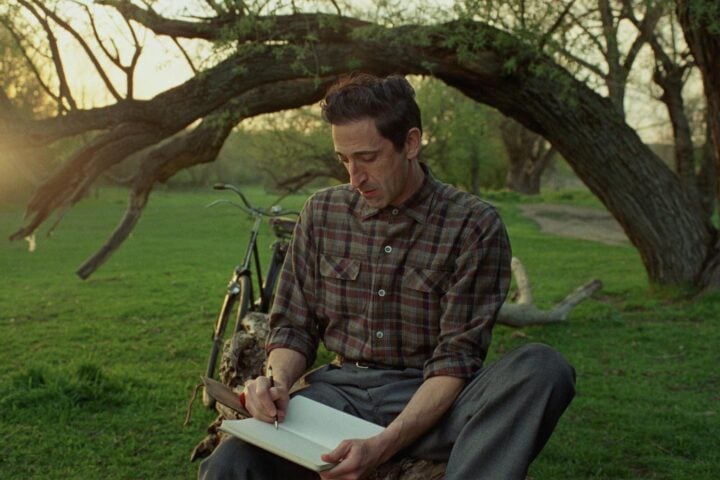

This large-scale design is shored up with certain small details. Jony’s red plaid hoodie recalls the cloak of a Darth Maul, yet he roams the village on horseback instead of hoverbike. Helicopter shots of the countryside make hay bales look like alien artefacts. There are also Lynchian flourishes, such as the comically inept officers, or Belzébuth’s marionette dance to a jazz combo—hardly the sweeping rehash of Wagner and Dvořák that we’ve come to expect from sci-fi films.

A climactic scene reminiscent of nothing less than Salvador Dali’s 1958 painting Religious Scene in Particles drives home the absurdity of the conflict at the center of Dumont’s film. The fleets of the 1s and 0s converge just outside of Earth’s atmosphere and inadvertently form a black hole that vacuums up every single vessel. It then vanishes, leaving everything else intact and the gendarmes, who witness the phenomenon from Earth, slightly more confused than before. Such an absurdist anticlimax is, of course, a slap to the face of operatic grandiosity.

Despite such standout moments, the film’s juxtaposition of a sleepy fishing village and epic themes is a gag that yields diminishing returns. As the entire story is caught up in the galactic machinations of 1s and 0s, there’s little meaningful interplay between the story and setting. What little character development we get is restricted to the interactions between Jony and Jane. For its big joke to sustain itself, The Empire would have had to present the village as a character in its own right, as opposed to a mere backdrop.

There are stabs at this with, for example, the gendarmes’ murder investigation, or when the Queen impersonates the village mayor and engages in small talk with an old lady, but neither amounts to more than a joke in passing. Failing, then, its promise to integrate the galactic and the humdrum into a story greater than the sum of its parts, The Empire smugly parodies tropes, however desperately in need of parody they may be, without managing to subvert them in any meaningful way, leaving the refreshment of the space opera to future practitioners.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.

If someone like you thinks this film is a mediocrity then I can only assume it’s fucking awesome.