Writer-director Matthias Glasner’s Dying, a nuanced anatomy of a dysfunctional German family, begins with Lissy (Corinna Harfouch) prostrated on the living room floor covered in feces and unable to move. Meanwhile, her husband, Gerd (Hans-Uwe Bauer), aimlessly parades around their apartment in the buff. Clearly withdrawn from reality, he doesn’t register Lissy’s presence, let alone her distress, as he walks in front of her.

We’ll learn across this poignant and unforgiving saga of the origins and results of lovelessness that this is an average day in the life of the elderly couple. And while it’s easy to read this disturbing opening as a raw portrait of the predicaments of old age, the scene is ultimately understood as the embodiment of an entire family’s sad state of affairs: It always seems as if someone in the Lunies clan is drowning in shit and everyone else is looking the other way.

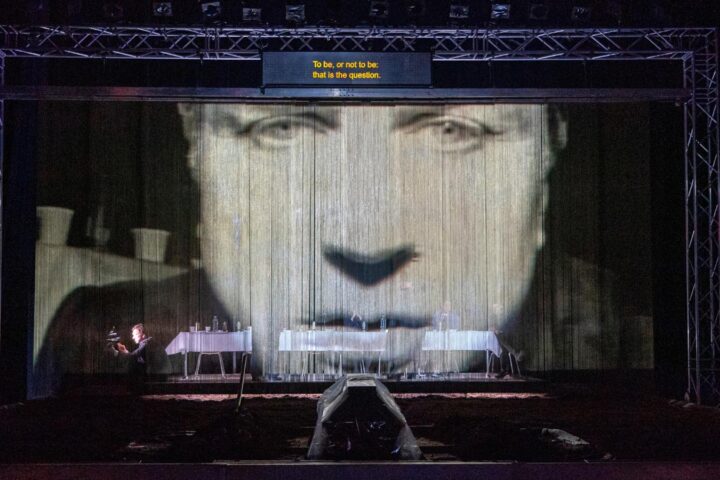

Following the opening chapter focused on Lissy and Gerd, the 180-minute Dying follow the ways in which their children also find themselves withdrawn from the reality of family life. Nobody here is capable of confronting the messy inconveniences of kinship—of expressing one’s feelings, of finding a common ground, of being emotionally responsible. While Lissy and Gerd’s son, Tom (Lars Eidinger), tries to find refuge in art (he’s a conductor tirelessly rehearsing a piece bearing the film’s title), their daughter, dental hygienist Ellen (Lilith Stangenberg), drowns her sorrows in alcohol at punk clubs in the company of a married co-worker (Ronald Zehrfeld) with whom she’s having an affair that’s clearly going nowhere.

The film’s five chapters offer multiple perspectives on the dysfunctions of the Lunies family from the perspective of a different member. Most catch glimpses of the same brief interactions between Lissy and Gerd with their children—or, rather, missed attempts at interacting with them, from phone calls to a funeral that Tom and Ellen miss.

While moments from the chapters overlap, they never feel repetitive. Throughout, Glasner’s approach suggests a sleuth in a domestic ethnography, tracing everyone’s brokenness to when Lissy, Gerd, and their children were all living under the same roof. As bitter revelations eventually pour forth, we find that the ties that bind are actually the ties that sever. But sometimes the severing is literal, as when the intoxicated sister pulls her intoxicated lover’s broken tooth with a sharp kitchen utensil before kissing his bleeding mouth.

In fact, the act of touching another person—or being touched—is a dominant motif of the film. Here, touch is seen as only being bearable if those involved are under a trance, numbed to its reverberations. And the after-effects of a touch seem to almost accuse human connection itself as something noxious, as in a sequence where Ellen develops a major allergic reaction post-coitus, as if the Lunies were too unaccustomed to affection for their bodies to handle it.

Dying abounds in such evocative articulations. The way Glasner pitilessly sees it, this family incarnates the cold-blooded bonds that stand in contrast to the unconditional love we normally associate with parent-child relations, to the point that to die in this context is a deliverance. And to be a true “partner,” which is how Tom calls his friend Bernard (Robert Gwisdek), who’s composing “Dying” for him to conduct, is to facilitate death. Indeed, the only real embrace in the film takes place when one of the characters is mid-death, when said embrace is a belated reminder of what one should have done to have made existence bearable, maybe even blissful.

The film’s diligent script and nuanced performances are such that the depressing material stops short of turning into a depressing experience. The ingenious structuring of the narrative, coupled with the disarming gravitas that the actors bring to their roles, results in one of the most visceral portraits of the nuclear family as a botched project. Dying is an enlightening punch in the gut, as Glasner offers the increasingly rare opportunity of a cinema that immerses us in the depths of the human experience without varnish or sentimentalism.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.

✨✨✨✨✨✨