To its credit, Rupert Sanders’s The Crow isn’t a mere rehash of Alex Proyas’s 1994 film. The central conflict is the same—a musician and his fiancée are murdered and the former is given the chance to return from the dead to avenge their death—but it expands on both the couple’s love story and the lore behind Eric’s (Bill Skarsgård) connection to the netherworld where the supernatural crows dwell. Unfortunately, in doing so, the remake gets bogged down by a superfluous, hackneyed backstory and narrative threads that are conspicuous for their lack of emotional gravitas, causing the film to feel like a wheel-spinning exercise.

For all its corniness, the original film cut right to the chase by opening with Eric and Shelly’s murder and allowing Eric’s bloody quest for vengeance to commence within a handful of scenes. Proyas understood the importance of narrative efficiency, along with establishing strong atmosphere and mood, relying on dingy, apocalyptic, Gothic-inspired set design and a goth-industrial-heavy soundtrack that, at the time, was more popular than the actual film.

In that earlier film, Detroit was meticulously transformed into something akin to a bleaker, grimier vision of Tim Burton’s Gotham City. By comparison, the cityscape in Sanders’s The Crow feels depressingly generic. Outside of the crow-ridden, purgatorial world that Eric repeatedly visits to dully confer with the vaguely defined guide Kronos (Sami Bouajila) over the conditions of his resurrection, much of the film is plagued by the underlit, monochromatic color schemes that one frequently finds in modern blockbusters.

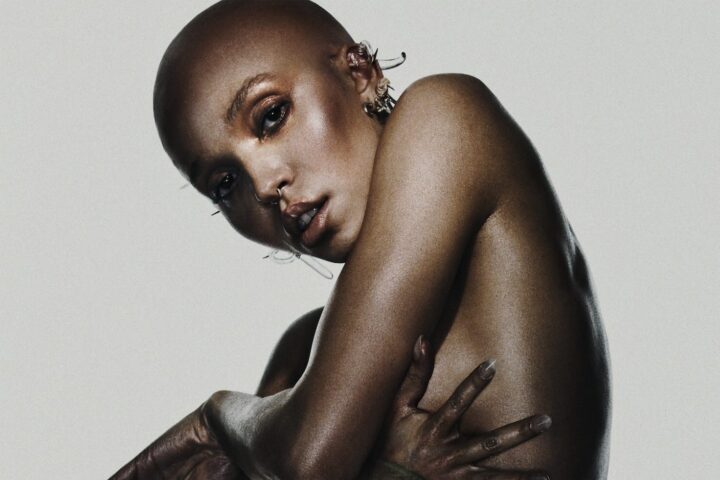

The unimaginative dourness of the film’s aesthetic is reflected in the disaffection that defines Eric and Shelly’s (FKA Twigs) relationship, and especially Skarsgård’s performance. We’re told that Eric is “brilliantly broken” and that Shelly likes Rimbaud, but in all the additional time devoted to their love affair, that’s about the extent of what we truly learn about them. At one point, Shelly jokingly asks that if they killed themselves, “Do you think angsty teens would build shrines to us?” It’s a welcome moment of self-aware humor—a reprieve from an overwhelming nihilism that’s neither earned nor examined—that’s not on display for the remainder of the film.

Danny Huston brings a winking skeeviness in his over-the-top portrayal of the main villain, Vincent Roeg, a business magnate who gained supernatural powers years ago by making a literal deal with the devil. But otherwise, the film rarely ventures into that same level of ridiculous excess, with the third-act showdown inside an opera house being the lone exception.

If there’s anything to recommend in this mostly flaccid, uninspired affair, it’s that sequence, which sees Eric taking dozens of bullets and shotgun blasts from the horde of armed guards there to protect Roeg, only to find increasingly creative and gruesome ways to slice through them with a short katana blade. It’s an amusing bit of lunacy—reaching its peak when Eric used the blade stuck through his chest to stab a man’s eye out—that strikes the perfect balance of preposterous hyperviolence and wounded desperation, hinting at the film that could have been.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.