While his work might not enjoy the iconic status of the Columbia Pictures classics that formed a key part of the retrospective programming at the 72nd Locarno Film Festival, Samuel Fuller is a director who’s nevertheless had a significant influence on the kind of independent cinema that the event seeks to champion. However, a screening of Fuller’s penultimate feature, Street of No Return, which formed part of this year’s Histoires de Cinema section at Locarno, couldn’t help but seem like an outlier in today’s film landscape.

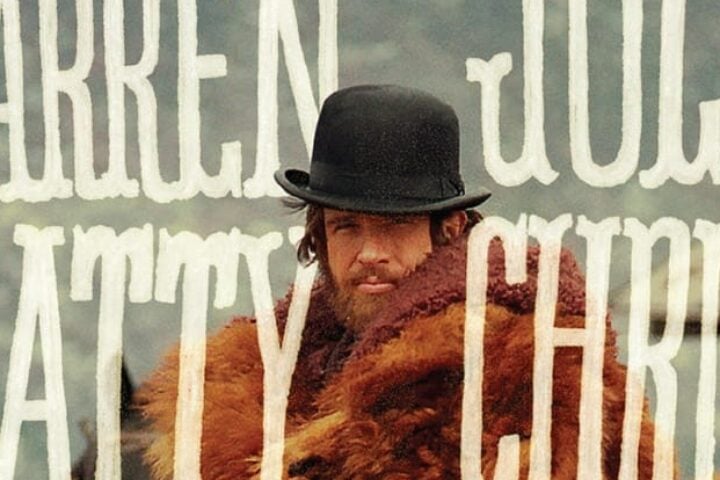

After its visually striking opening sequence sees a gang war waged in the streets of an absurdly rundown, almost post-apocalyptic city, the 1989 film follows a homeless man (Keith Carradine) as he tracks down a former lover (Valentina Vargas) and seeks revenge on the drug dealer (Marc de Jonge) who cut his throat and ended his career as a chart-topping, globe-trotting singer.

A riotous ’80s time capsule that reveals its main antagonist to be in cahoots with the mayor and local police as part of a scheme to flood impoverished Black neighborhoods with crack cocaine, Street of No Return exemplifies Fuller’s direct storytelling and the confrontational, broad-strokes sincerity of his politics. And its unaffected embrace of genre feels particularly potent in an era where hollow nostalgia, studied revisionism, or prestige pastiche are common.

Premiering at the festival this year and fueled by a rare starring role for Tim Blake Nelson, Vincent Grashaw’s Bang Bang demonstrated a more contemporary, ambivalent approach to the confines of genre. It revolves around washed-up prizefighter Bernard “Bang Bang” Rozyski, a former featherweight champion with little left to show for the steady stream of big-money purses he enjoyed in his youth. Embittered and alcoholic but retaining much of his fighting spirit, he takes Justin (Andrew Liner), the wayward son of his estranged daughter, Jen (Nina Arlanda), under his wing and trains him to enter the local boxing circuit, mostly ignoring his grandson’s general lack of interest or enthusiasm regarding the sweet science.

Rozyski’s volatile decrepitude is mirrored in the film’s crumbled, unstable urban setting, a post-industrial Detroit whose fall from grace the man regularly laments, though without expressing any desire to see conditions improve. In fact, his disgust at the revelation that Justin’s community service has him working unpaid to clean up the city is a clear indication of his defeatist, self-destructive attitude. Both his anger at the untimely end of his career and his disappointment with the compromised present-day reality that he inhabits find an outlet in the figure of Darnell Washington (Glenn Plummer), a former boxing rival who has since become independently wealthy and is now running as a Detroit mayoral candidate.

Constructed almost entirely of worn-out boxing movie tropes, with the acerbic bon mots of Will Janowitz’s on-the-nose script doing little to tether it to reality, Bang Bang nevertheless has a rawness that keeps it engaging throughout. Blake Nelson is a charismatic presence at the heart of a uniformly excellent cast, though the earthy underdog charm poking out from beneath his macho persona does make him seem an unlikely former pugilist. With nuanced performances and an appealingly low-key, grimy aesthetic, Grashaw’s film hits a sweet spot between generic comeback story and lived-in character study, stopping just short of romanticizing its squalid milieu and dodging sentimentality more often than might be expected.

A final confrontation between Rozyski and Washington pushes Bang Bang far beyond the realms of plausibility, but also serves to underline the inherent absurdity of men rewarded for successfully channeling their emotions into physical violence. Ultimately, Grashaw attempts to retroactively excuse his indulging of clichés by implicating the heroic fighter archetype itself in the film’s most tragic developments. While its dialogue might spell that point out a little too explicitly, there’s a refreshing lack of catharsis or resolution in Bang Bang’s depiction of bruised masculinity and squandered human potential.

Another conspicuously de-glamorized tale of violent characters on society’s fringes, Death Will Come is a less successful engagement with familiar genre fare. Christoph Hochhäusler’s thriller is set primarily in Luxembourg and Germany, but with the glacial pace, washed-out palette, and minimalist interiors of a Nordic noir. It paints a bland picture of mid-level organized crime and widespread moral rot in and around anonymous metropolitan enclaves, in which stylish contract killer Tez (Sophie Verbeek) is enlisted by veteran gangland boss Charles Mahr (Louis-Do de Lencquesaing) to investigate the murder of one of his most trusted couriers.

Hochhausler’s fourth feature has a satisfying surfeit of procedural detail, but it’s a little too restrained for its own good, with flat characters and a general lack of dramatic tension that a showman’s touch might have gone some way toward concealing. Boasting an androgynous look and a steely diligence that rarely cracks her calm demeanor, the enigmatic Tez does make for an intriguingly unconventional protagonist, though the contract killer’s motivations and background are ultimately too obscure for her to do anything other than advance the plot.

Early on, a cutting-edge new line of sex dolls is introduced as a potential threat to the brothel business from which Mahr has made his fortune, suggesting the inexorable encroachment of a more impersonal, sanitized modernity. Had this theme been developed further, the general sense of inertia and redundancy that the film exudes would perhaps have been more affecting. As it is, Death Will Come reveals tasteful European ennui to be a far less effective response to the faded glory of an old way of life than Bang Bang’s indignant gut punch, not to mention the stylized carnage of Street of No Return’s clear-eyed, unashamed power fantasy.

The Locarno Film Festival ran from August 7—17.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.