One of the most enduring debates about Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” soliloquy is whether it is, indeed, a soliloquy. Is the prince of Denmark aware that, just beyond the curtains, the king and Polonius are spying on him? If he is, should we rather call Hamlet’s speech a performance, meant to further his plot to be thought of as a decaying madman? If he isn’t aware of being surveilled, how serious should we take Hamlet’s consideration of suicide?

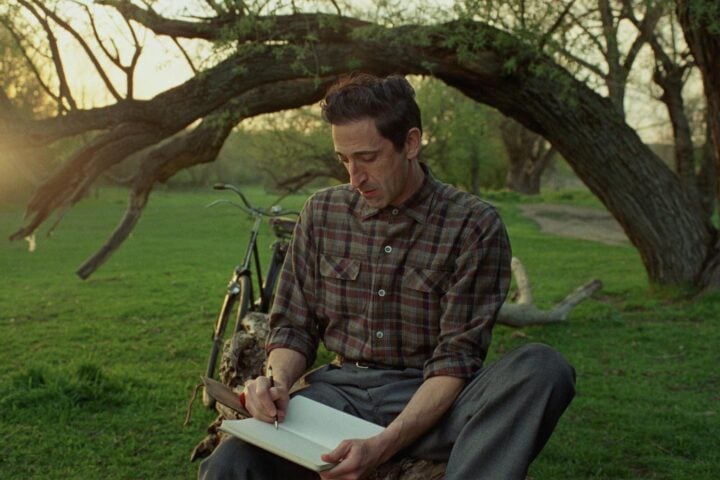

Greg Kwedar’s loosely fictionalized Sing Sing, about a theater troupe at the titular prison, isn’t an adaptation of Shakespeare’s play. But the original comedy that the incarcerated actors are rehearsing, a musical revue about a time-traveling ancient Egyptian titled Breakin’ the Mummy’s Code, does contain Hamlet’s speech. Still, the film hinges on familiar Shakespearean themes, exploring how art can be a conduit for catharsis and, as in Hamlet, asking what freedom really looks like when it seems like there’s no way to stop walls from closing in on you.

Sing Sing is based on “The Sing Sing Follies,” a 2005 Esquire article by John H. Richardson, as well as personal interviews that Kwedar and co-writer Clint Bentley conducted with current and former participants in Sing Sing’s Rehabilitation Through the Arts (RTA) program, many of whom play versions of themselves here. John “Divine G” Whitfield (Colman Domingo) struggles to prove his innocence after a decade behind bars while simultaneously helping to run the RTA program. A devoted artist and mentor to his colleagues, he writes scripts and recruits new actors, including the violent Clarence “Divine Eye” Maclin. Eye has a reputation at Sing Sing as a “yard dog” particularly adept at extortion, but beneath his veneer of intimidation, he displays a particular fascination with Shakespeare, and can quote King Lear to emphasize his plight.

Despite his hesitancy toward a new mode of self-expression, Divine Eye displays raw talent and provides the group with the suggestion that the prison’s inmates may crave comic escape, rather than the variety of heavy drama that’s come to define RTA’s programming. G’s ego as the group’s sole professional artist initially hampers his ability to accept Eye’s rising star, but the two Divines eventually form a bond that challenges both of their understandings of masculinity, responsibility, and artistry. At the same time, both of them prepare for appeal hearings in conversations that resemble more and more the structure of performance rehearsals.

This is a film of noble intentions, and it boasts vulnerable performances from its mostly amateur cast. That it’s a result of such an open partnership with people who’ve been incarcerated is especially laudable, as so many films set inside correctional facilities don’t accurately represent the people for whom they seek to advocate. Still, while the film appreciatively gives a voice to the experiences of those who’ve spent years locked up, some for crimes they didn’t commit, its focus on their individual struggles comes at the expense of not casting enough light on the racist and classist infrastructure that ensures the men’s incarceration.

Sing Sing is also riddled with overwrought exposition, some of which is unnaturally inserted into scenes. It’s a film that feels entirely too eager to relay its noble intentions, highlighting in scene after scene how each character cherishes the privilege of participating in RTA, how being able to act provides them with a metal escape from their incarceration, and how frustrating it can be to be divorced from “real” life. The spreading out of screen time and attention to each participant can make the film feel like an advertisement for the real-life RTA rather than the incisive critique of systemic racism and classism that it purports to be.

Still, Sing Sing does succeed in advocating for a more humane treatment of the incarcerated. One of the film’s stronger choices is in concealing, for the most part, what has put these people behind bars. People who have been incarcerated are frequently, and insensitively, asked what has put them in jail, and the writers’ refusal to indulge in this curiousness allows the viewer to see these people for who they are, rather than as merely criminals or as hapless victims.

In its depiction of actors flourishing through artistic struggle, Sing Sing ultimately argues that the most effective liberation happens through the freeing of the body as well as the soul. For it is in the understanding of experiences beyond our own that true freedom is found.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.