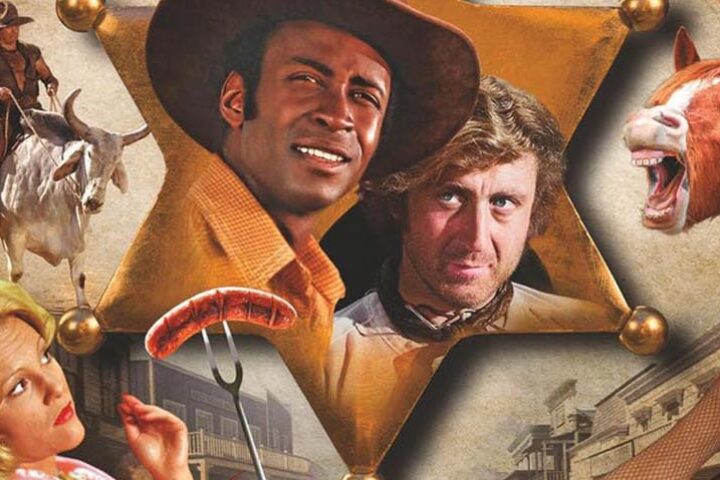

Robert Benton’s Bad Company does for the western what Bonnie and Clyde, Benton’s earlier collaboration with screenwriter David Newman, did for the gangster movie, only without that film’s veneer of star-powered sex appeal. The scrappier Bad Company consistently undermines the romanticized notions of the frontier that underpinned several generations of genre filmmaking. The film especially takes direct aim at two of our nation’s dearest held myths: the Horatio Alger notion of economic self-sufficiency, and the destiny of political expansion manifest in Horace Greeley’s famous dictum: “Go west, young man!”

The film is also decidedly of a piece with the year of its release in 1972, evident from the very first scene, wherein we see a young man dragged kicking and screaming from his home by blue-clad Army soldiers to be conscripted into the Union cause. The moment is given a surreal punchline by the fact that the boy wears women’s clothes. What’s more, he’s not the only on so attired in the cage-like wagon into which he’s promptly tossed. The Vietnam war and the draft wouldn’t be far out of mind to a contemporary viewer.

On the run from all that, and provided with a grubstake by his parents (Jean Allison and Ned Wertimer), who’ve already lost one son to the war, Drew Dixon (Barry Brown) lights out for the territories to make his way in the world. But a wrench is almost immediately thrown into those plans after he’s bushwhacked by amiable rogue Jake Rumsey (Jeff Bridges). After some rigorous bits of rough-and-tumble that more or less establish their parity, Jake invites Drew to team up with him and his ragtag gang of lost boys, which includes 11-year-old Boog (Joshua Hill Lewis).

What follows is a textbook example of the western as episodic road movie, as if Budd Boetticher had directed Easy Rider but with horses instead of bikes. We trail our juvenile band of outsiders as they run up against a series of obstacles that gradually strip away their youthful illusions. One by one, they come to question their proficiency as gunslingers, the cost (literal and figurative) of sexual initiation, even their loyalty to one another as their numbers slowly dwindle.

The wannabe wild bunch’s descent into an existential hellscape signified by stunted trees and sun-scorched grasses is initiated by a scene that’s disarmingly comic at first. Trying to provide for his compatriots, Boog once again swipes a pie cooling on a windowsill, only this time to have his head blown off by an irate farmer (Charles Tyner). It’s a truly shocking sequence, not least for the abrupt shift in emotional register, not to mention the borderline surreal sight of Boog’s tiny body lying face down in a yard full of squawking chickens.

Bad Company proves unwaveringly distrustful of adults and authority figures. Along with the army “recruiters” from the first scene and that trigger-fingered farmer, we’re also introduced to a penniless homesteader (Ted Gehring) who pimps his wife (Monika Henreid) to the gang for eight bucks, an aging bandido named Big Joe (David Huddleston) who cleans the boys out at gunpoint, and a Marshal (Jim Davis) who’s more interested in stringing up criminals than he is in their guilt or innocence. Corruption and mercenary behavior in the face of a hardscrabble existence are the norm. Death, when it comes, confers no dignity.

Bad Company can also be seen as the cinematic equivalent of a bildungsroman, a work that traces the influence of events on a young person’s developing sensibility. From grandiose dreams of life as a cattle baron, and despite his initial adherence to a self-imposed code of conduct, Drew is steadily reduced to a life of crime. Where Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid ends on a freeze-frame that saves us from having to see our heroes’ bloody demise, the one that closes Bad Company indicates that Jake and Drew are locked into the all too imaginable consequences of their criminal behavior. So that Drew’s final exhortation “Stick ‘em up!” plays like a grimly ironic version of Bonnie Parker’s declaration: “We rob banks.”

Image/Sound

Fun City Editions presents Bad Company in a new 4K restoration, sourced from the original camera negative, and the result is revelatory, doing full justice to Gordon Willis’s moody cinematography. The film’s deliberately muted color palette comes across strongly, with the frequently shadow-laden interiors clearly discernible and without evident black crush. Grain looks consistently well-tended. Audio comes in Master Audio stereo, which is clean and clearly delivers the piano-driven score from composer Harvey Schmidt.

Extras

The major supplement here is a commentary track by critic Walter Chaw, who focuses heavily on the film’s themes and visual strategies, details the history of collaborations between director Robert Benton and screenwriter David Newman that stretches from Bonnie and Clyde to Still of the Night, and recounts the sad story of co-star Barry Brown’s death by his own hand as related in his brother’s memoirs. Also included is a trailer, image gallery, some radio spots, and an illustrated booklet that contains an insightful essay by critic Margaret Barton-Fumo that places Bad Company in context both as a revisionist western and a comment on the war in Vietnam.

Overall

Robert Benton’s Bad Company is a downbeat revisionist western that deflates generic mythmaking while also saying a few choice things about its own day.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.