Michael Ritchie’s Prime Cut never quite recovers from an early botched opportunity. Up until then, Ritchie effectively primes us for the reveal of the film’s big bad, seemingly eavesdropping on characters in a Chicago bar as they trade exposition pertaining to Mary Ann (Gene Hackman), the owner of a meatpacking plant who uses his business as a front for running drugs and prostitutes.

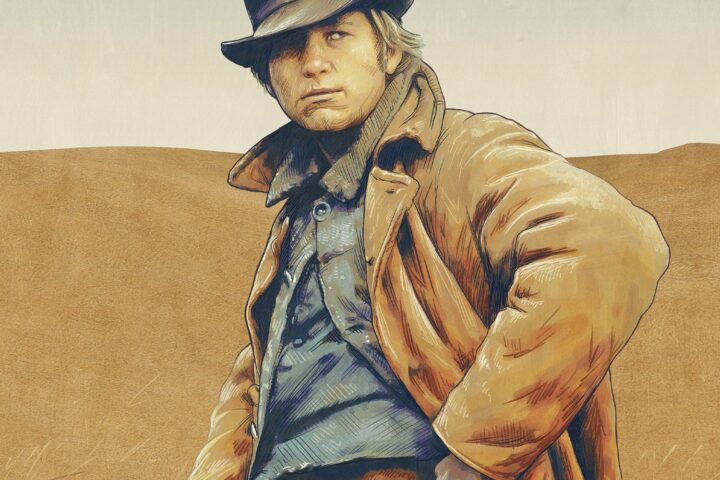

The trouble is that Mary Ann’s supposed to pay up to some folks in Chi-town, who claim he owes them half a mil, and that’s where enforcer Nick (Lee Marvin) comes in, swinging down to the former’s fortress in Kansas City in a limo fully decked out with guns and expendable goons. Nick and Mary Ann have a history, of course, working for the same bosses, sleeping with the same gold-digging henchwomen. After first stopping at an atmospherically sleazy flophouse, Nick walks right in on one of Mary Ann’s cattle calls, where he keeps drugged sex slaves in pens, treating them quite literally as livestock. (This is the film’s most perverse and resonant image.) Mary Ann is smugly talking business with hangers-on, eating a big, steaming pile of spicy, fried beef guts, when Nick saddles up and tersely taunts him as only a Lee Marvin character can. And then, splat. They go their respective ways, Nick stealing a slave, Poppy (Sissy Spacek), from Mary Ann out of sympathy for the woman’s drug-induced stupor.

The build-up to this encounter, which includes an unnerving opening credits sequence that appears to show real cattle being grounded up into sausage, is piffled away by the abject pointlessness of Nick and Mary Ann’s initial re-meet-and-greet. One obviously doesn’t expect the two to kill each other in this scene, but there’s a reasonable expectation that Mary Ann will capture Nick, or that one of them will evade the other’s murder attempt. Or something, anything, to shift Prime Cut into the next gear.

When Al Pacino and Robert De Niro’s characters merely have coffee at Heat’s halfway mark, the scene is understood as a joke on the actors’ respective iconographies as well as a sly acknowledgement of the pretense of civility that keeps the men from immediately settling their irreconcilable differences. That sentiment is macho and derivative of hundreds of westerns, but it suits the film’s comic-book existentialism, elevating the stature of the duo’s parallel obsessions. The characters in Prime Cut, though, are all outlaws entirely within the parameters of their own shadow world. There’s no logic, and no punchline, to this delay of minor visceral gratification. The antihero and the antagonist walk away from one another simply because there are two acts left in the narrative, though everyone remains subsequently stuck on page one.

Consequently, everything that follows this sequence is unavoidably suggestive of treading water. Nick wanders around Kansas City, intimidates a few of Mary Ann’s associates, enjoys some sexy innuendo with a memorably outfitted moll, Clarabelle (Angel Tompkins), assumes a creepy surrogate father/lover position in Poppy’s life, and generally screws around until it’s time to kill Mary Ann for real, in time with the climactic finish. Along the way, Ritchie offers self-consciously striking images of cars driving toward the foreground of the frame, and a well-staged shoot-out that’s set, with somewhat studied eccentricity, in a sunflower field.

Hackman, the film’s gaudy life force, is off screen for far too long during this stretch, though Marvin commands our attention with his physicality. (There’s a reason John Boorman spent so much of Point Blank’s running time trailing the actor as he marched down hallways. That walk contains more excitement than most conventionally elaborate set pieces.) But there’s little tension to anything that happens. Most of the film’s scenes are competently orchestrated on their own terms, but appear to exist in isolation, detached from every other surrounding moment. Prime Cut lacks the rude, propulsive intensity of Marvin’s best vehicles.

Image/Sound

Kino’s 2160p UHD presentation beautifully renders Gene Polito’s exquisite Panavision cinematography, from the gritty cityscapes to the windblown wheat fields. Colors are vibrant, fine details of costume and décor vivid, and the grain structure meticulously balanced. Audio comes in stereo or surround, the latter nicely opening up some of the noisier crowd scenes like the indelibly rendered fun fair. Both options do well by Lalo Schifrin’s indelibly nuanced score.

Extras

Aside from a slate of Lee Marvin-centric trailers, Kino’s release comes with two nicely complementary commentary tracks. Marvin biographer Dwayne Epstein offers a lot of information about Michael Ritchie’s film—gleaned largely from interviews given by actors Gregory Walcott and Angel Tompkins—a lot of which concerns Marvin’s off-screen behavior. Critics Steve Mitchell and Nathaniel Thompson engage in a lively conversation that focuses on Marvin’s life and career, Ritchie’s penchant for social commentary, the film’s thematic and aesthetic concerns, and how Prime Cut serves as a bridge between classic and New Hollywood.

Overall

Prime Cut is a grimly off-kilter crime film that examines the line separating man and beast.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.