Charlie Shackleton’s Zodiac Killer Project is a phoenix of sorts, born of twin failures. CHP Officer Lyndon E. Lafferty was convinced that he had discerned the identity of the Zodiac Killer, which of course he never proved. In 2012, Lafferty’s The Zodiac Killer Cover-Up: The Silent Badge was published, and later Shackleton was in the process of turning the book into a true-crime documentary, until the author’s family decided not to grant the filmmaker the rights to the material. Lafferty, who died in 2016, had no say in the matter. Lafferty and Shackleton are united, then, along with many others, in having been eluded in various fashions by the Zodiac Killer, who’s become a latter-day Jack the Ripper in the American imagination.

It’s not difficult to see why the Zodiac Killer haunts us. With his flamboyant taunting and cryptology, he’s a Hollywood boogeyman made real. He’s come to exist, along with Charles Manson and the violence at Altamont, as shorthand for America’s hangover after Vietnam, the erosion of the counterculture, and more. And the Zodiac Killer never got caught, which is great for cementing a legacy. A killer uncaught has a way of mocking our illusions of security, which committed obsessives take it upon themselves to try to restore as a way of shoring up their own worth. Zodiac Killer Project thrives on this sense of obsolescence, of haunted irresolution.

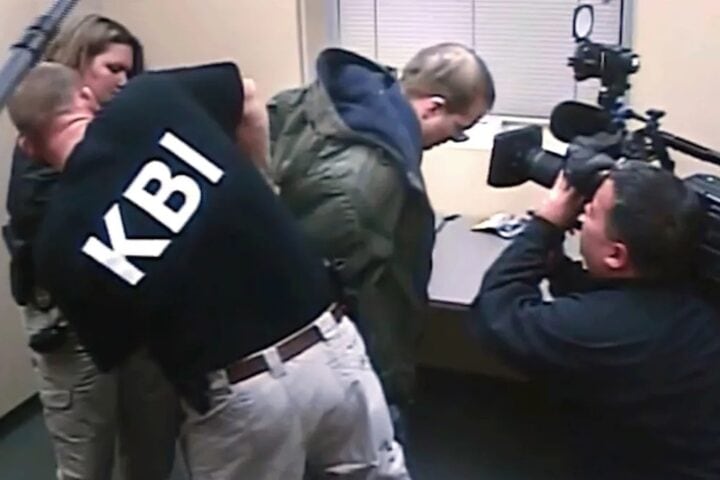

In Zodiac Killer Project, Shackleton supplies in voiceover the story that he would have told in his true-crime doc had he gotten to make it, and, rather remarkably, he doesn’t appear to be invested in what he’s selling. Lafferty’s story, as Shackleton frames it, is a concoction of coincidences and contrivances that unsurprisingly refuse to go anywhere—typical conspiracy fodder, in other words, that derives its power from its impossibility to either prove or disprove, except perhaps in the court of common sense. By his own apparent admission, Lafferty bent the law radically, stalking and mounting illegal undercover operations and even coming to socialize with the guy he assumed to be the Zodiac. Shackleton relates to this material primarily in terms of how it will look on screen, bolstering his attempts to sell himself as a filmmaker.

Shackleton’s voiceover, which spans the film’s entire 91 minutes, is a paradox, absorbing precisely for its coldness, irony, and lack of emotional commitment. The filmmaker’s vocal performance is a pointed refutation of the heated melodrama that often drives true-crime docs. Shackleton presents less as a dashed conspiracy theorist or idealist than as a film critic both frustrated and enthralled with the conventions of a genre. Shackleton has been a film critic in fact, and he utilizes criticism to intensity the conventions of true-crime shtick.

The minimalist filmmaking here is incredibly effective, rich in empty tableaux of the Bay Area that invite us to supply our own monster in the shadows or sunshine. Shackleton connects his alienation from the true-crime genre to the alienation of those enthralled with the Zodiac Killer. He builds an enthralling true-crime doc by taking the form apart, in essence allowing true-crime addicts, this critic included, to have their cake and eat it too.

Zodiac Killer Project is less flashy than most true-crime docs, and that’s to its credit, as the pared-down images and deliberate pacing, united by Shackleton’s voice, give us room to stew in our dread. The flash of most of these kinds of docs doesn’t allow audiences to savor much, which is the point: They’re stitched together from nuggets of aural-vision stimulation, a blend of tabloid, TV series, and podcast that’s rigorously designed to be only half-watched.

Interspersed with Shackleton’s recall of the Lafferty narrative are asides in which the filmmaker dismantles the clichés of true crime, which often spin stories out of virtually nothing, relying on recreations and B-roll footage and hasty assumptions so heavily that the productions become nothing more, though perhaps less, than fiction. Less than fiction because this stuff is supposed to be taken vaguely seriously, passed off as the truth, informing our biases whether or not we consciously “believe” what we are seeing and hearing.

Shackleton compares footage from various true-crime docs, mostly miniseries, including heavy-hitters like Andrew Jarecki’s The Jinx, and surgically mines them for bullshit. We hear of voice actors who fill in for real participants, the audio accompanied by a shot of a tape recorder—a shot that could’ve been lifted from any source or staged anywhere—to misleadingly connote journalistic impartiality. Think of all the shots from any number of docs—of tape recorders, open doors, hallways, swinging lamps, glaring flashlights—that are pure fabrication.

Shackleton amusingly observes that the first scenes of a true-crime doc often serve as a trailer for the show that you’re already watching. An insidious merging of fact and fiction often carries over to the behavior of interview subjects as well, who have been conditioned via other such productions to play to the stereotypes that they know the filmmakers want, such as the macho cops who talk in the gruff cadences of characters from countless movies and TV shows. And of course there are the folks who can be counted on to say that the neighborhood of a killer was the most idyllic place that you ever saw. Few of Shackleton’s observations are likely to shock people, but the preponderance of them, as cunningly assembled here, is an eerie reminder of how casually and often and quietly the media can bend our perception of our world.

Zodiac Killer Project is a wicked embodiment of Marshall McLuhan’s notion of the media itself being the message. The tropes of true crime work even when used by Shackleton sarcastically and preceded by explorations of their phoniness. Those cuts of B-roll nothingness—from those ridiculous noir-ish images of people with their backs turned to us, strolling shadowy corridors, to those quick cuts of close-ups of murder weapons—are the audio-visual equivalent of tasty, greasy fast food. These reductive gimmicks are shallow and lurid and bad for you but also satisfying precisely for those very qualities.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.