When it comes to movies, timing is everything. Sexy, scary, and occasionally clumsy, Carmen Emmi’s feature-length directorial debut, Plainclothes, is an anxious and unabashed gay drama about social repression and its impacts. Set in 1997, what might a mere few years ago have been an easily digestible snapshot of an ugly, less liberated gay past is now a bitter pill with something to say about our precarious present.

Lucas (Tom Blyth) is a young police officer tasked with targeting local cruising spots in Syracuse, New York, by luring men into bathroom stalls and charging them with public indecency. Struggling with the recent death of his father and gripped by crippling anxiety, Lucas nonetheless finds himself drawn to one of his targets, Andrew (Russell Tovey), an older, married man who slips Lucas his number after he fails to make the arrest. As their sexual relationship develops, Lucas’s romantic feelings toward Andrew present challenges to his professional life, his personal obligations to his grieving mother (Maria Dizzia), and his sense of self.

Mixing contemporary digital photography with lo-fi surveillance, home movie, and other Hi8 footage, Emmi and cinematographer Ethan Palmer create a consistently surprising and inventive visual landscape that gives the audience a sense of the past and present bleeding into each other. The approach isn’t merely transportive, as it also knits Lucas’s debilitating anxiety into the visual fabric of Plainclothes—adding a sense of disorientation for viewers as we consume the nonlinear narrative in fluttery, disordered fragments.

The filmmakers always feel as if they’re trying something new with the conceit, whether it’s using the disruptions by the lo-fi footage to put the viewer directly in Lucas’s POV or more expressionistic flourishes as the young man’s world comes increasingly apart. The film is shot in a retro 4:3 aspect ratio to claustrophobic effect, making every frame a tight squeeze stacked top to bottom with flop-sweat unease and barely controlled panic.

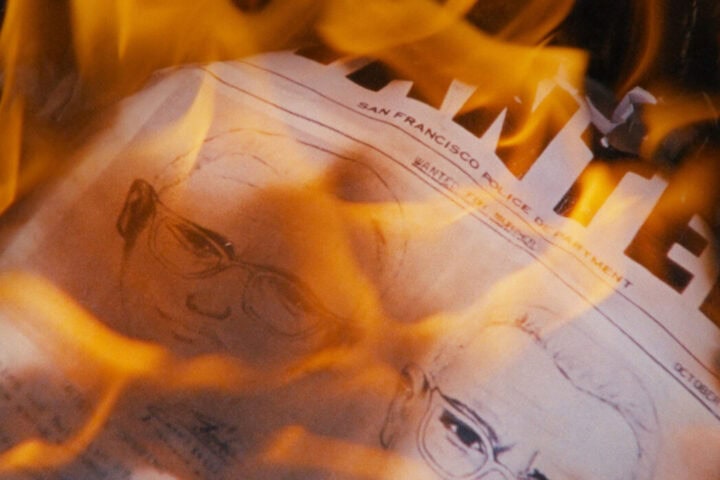

The visuals also call to mind the very surveillance images that have been used to criminalize gay men for decades. Emmi was reportedly inspired to write the script upon reading about a 2016 discriminatory lewd-conduct sting, and the film uses what appears to be actual footage from similar stings carried out prior to 1997 as a way to underscore the theme that repression is cyclical and deceptive police operations of the kind depicted here aren’t and have never been about public safety but stoking a climate of fear in a repressed minority. Ultimately, Plainclothes is a film about images, and the cold, lubricious, leering gaze of the film’s police force sharply contrasts with the contemplative, overwhelming emotiveness of Emmi’s own cinematic eye.

Blyth and Tovey give stirring performances that externalize the film’s obsession with images. The aspect ratio makes Blyth feel both imposingly large and impossibly beautiful, the exact sort of person one could imagine being used as bait on a hook for this type of operation. He ably rides the film’s waves of raw-nerve intensity to an unexpected climax that goes over the top but feels grounded in the emotional truth of a character trapped by the image his family has of him. But it’s Tovey who gets to verbalize an exhausting, soul-smothering loneliness that anyone for whom the normative, life-shaping pleasures of a marriage, career, and family only feel achievable cut off from their inborn sexual identity will find painfully poignant.

Though not as provocative as Sam H. Freeman and Ng Choon Ping’s Femme or as emotionally complex as Andrew Haigh’s All of Us Strangers, Plainclothes is still uncompromising for the way it shows how the ghosts of the past stretch their fingers toward an uncertain future. In the harsh light of 2025, the film’s snapshot of its 1997 setting doesn’t look like yesterday. Rather, it’s tomorrow, it’s today—a haunted cinematic everywhen where progress isn’t promised and the shame and loneliness of sexual repression are made perpetual in the flash of police lights, the grave faces of mothers, and the inescapable hum of video static.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.